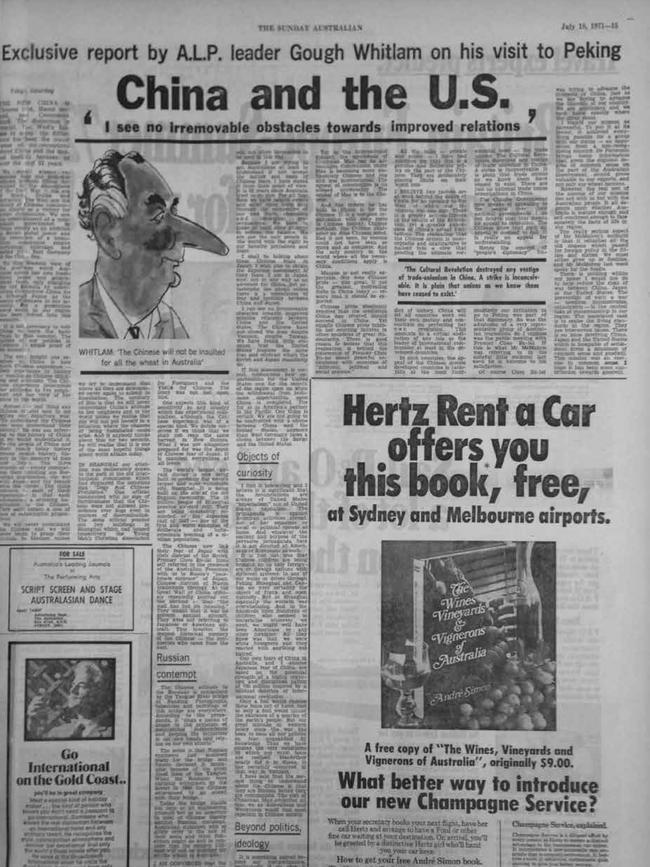

Gough Whitlam: on China and the US

We will never understand the Chinese unless we try to understand that above all they are determined never again to submit to humiliation.

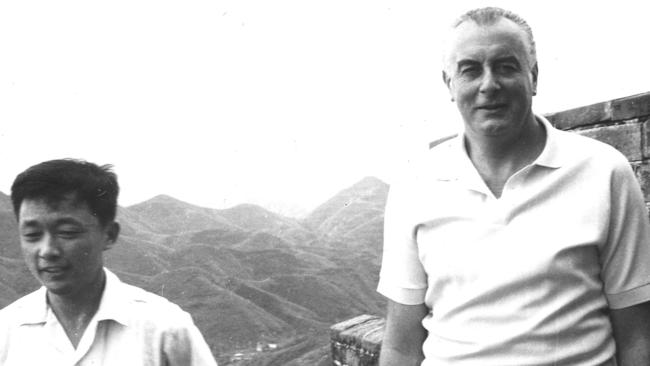

‘I see no irremovable obstacles towards improved relations’, writes Labor leader Gough Whitlam in his exclusive report on his visit to Peking, published in The Australian on July 18, 1971.

The new China is Chinese first, Maoist second and Communist third. The distinction is crucial. The West’s failure to accept the difference has been the major cause of misconceptions about China and the mutual hostility between us over the past 22 years.

We should always remember that our post-war policies towards China developed in the atmosphere of the Cold War – the era of Stalin, Dulles and McCarthy. The West saw the victory of Chinese communism simply as a victory for Soviet communism. We saw the establishment of a communist government in China simply as an addition to Soviet global power and the extension of a monolithic communist empire stretching unbroken and united from East Germany to the China Sea.

To this Western view of the post-war world Australia added her own traditional racial and geographical fears, only changing the old formula by substituting Communist China for a defeated Japan as the source of menace to our security.

For a generation every event in our region has been forced into this scenario.

It is not necessary to visit China to learn the basic flaws in this concept. The failure of our policies in Vietnam is ample proof of its unreality.

The real insight one receives in China is how much Chinese experience – their experience in history – dominates Chinese thinking and attitudes. The Chinese experience determines her attitudes to her neighbours and her view of her place in the world.

Almost the last thing any Chinese official said to me before our departure was: “To understand the Chinese you must understand their history.” He was not referring to the history of China as we would understand it. To the people of China and their rulers today history means recent history, history in the memory of men now living. The three strands of memory dominating their thinking are European imperialism, the war with Japan and the breach with the Soviet. The thing common to each of these experiences is that each represented a crushing humiliation to the Chinese. They each meant a loss of face of catastrophic proportions.

We will never understand the Chinese and we will never begin to grasp their attitudes to Maoism unless we try to understand that above all they are determined never again to submit to humiliation. The corollary of this is that we will never understand China’s attitude to her neighbours and to the world unless we realise that she will not put herself in a situation where the chances of being humiliated could arise. And if anybody thinks about this for two seconds, he will realise that it is one of the most hopeful things about world affairs today.

In Shanghai our attention was deliberately drawn to the park in the old international commission which had displayed the notorious sign “Dogs And Chinese Prohibited.”

One official commented with no sign of facetiousness that the Chinese were not allowed preference over dogs even in matters of discrimination. The same official pointed out two buildings in Shanghai which had housed respectively the Young Men’s Christian Association for Foreigners and the YMCA for Chinese. The irony was not lost upon him. One expects this kind of sensitivity in any country which has experienced colonialism, although the Chinese experience was of a special kind. We delude ourselves if we think that we shall not reap the same harvest in New Guinea.

What I was not altogether prepared for was the depth of Chinese fear of Japan. It is manifest everywhere at all levels.

The world’s largest air-raid shelter is now being built in probably the world’s largest and most vulnerable city, Shanghai.

It is being built on the site of the old English racecourse. The 10 million people of Shanghai practise air-raid drill.

They are being constantly reminded of the Japanese raid of 1937 – one of the first and worst examples of deliberate and indiscriminate bombing of a civilian population.

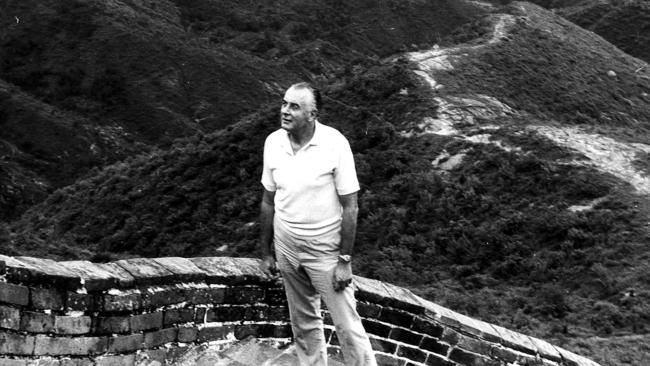

The Chinese now link their fear of Japan with their distrust of the Soviet. Premier Chou En-lai himself referred in the presence of the Australian Pressmen with us to Russia’s “passionate embrace” of Japan. Chinese distrust of Russia transcends ideology. At the Great Wall of China officials repeatedly pointed out the obvious – that “the wall has lost its meaning.” They meant that it was no defence against aircraft. They were not referring to Japanese or American aircraft.

This involves the deepest historical memory of the Chinese – the conquerors who came from the West.

Russian contempt

The Chinese attitude to Russians is symbolised by the Yangtse River bridge at Nanking. Photographs, tapestries and paintings of this bridge are everywhere. According to the propaganda, it “sings a paean of praise to the principle of maintaining independence and keeping the initiatives in our own hands and relying on our own efforts.”

The point is that Russian engineers had analysed plans for the bridge and finally declared it impossible because of the great flood tides of the Yangtse. When the Russians were abruptly withdrawn by the Soviet in 1960 the Chinese determined to go ahead with their bridge.

Today the bridge stands not only as an engineering triumph but as an assertion in steel of Chinese dignity against Russian contempt. Australian ministers who so glibly refer to the sale of their souls and trout fishermen might do well to consider that the modern Chinese will not be insulted for all the wheat in Australia.

I am convinced that the highest challenge to western statesmanship in our region and probably in the world now involves the relations between China and Japan.

Our response should lie in trying to moderate Chinese fear of Japan. We can only do this if we do in fact discourage any renewal of militarism in Japan. China has been on the receiving end since 1894. It would be folly of the highest order if we were now to force or encourage Japan into a role of appearing as our client bulwark against China. Among other consequences it would undermine democracy in Japan. It is my deep hope that the Japanese people will not allow themselves to be used in this way.

Because I am trying to get Australians at least to understand if not accept the nature and basis of Chinese fears, I have stated it from their point of view. It is 22 years since Australia tried to do this. For all that time we have judged events and acted upon them only through the perspective of our own fears, obsessions and ideological preoccupations. We have to make at least some attempt to redress the balance. We are not the only people in the world with the right to our favourite prejudices and fears.

I shall be talking about these Chinese fears in Japan. I wish also to obtain the Japanese assessment of their fears. I am in Japan now, not in any way as an advocate for China, but catastrophe lies ahead unless there is a moderation of fear and hostility between China and Japan.

I can see no irremovable obstacles towards improved sensible relations between China and the United States. The Chinese have not closed the door despite Vietnam, despite Taiwan. We have found little evidence that the United States inspires the same fear and mistrust which the Soviet and Japan manifestly do.

If this assessment is correct, tremendous new opportunities for the United States and for the benefit of the region open up when the withdrawal from Indo same opportunities open China is completed. The for us as America’s partner in the Pacific one thing is certain. We are not going to be confronted with a choice between China and the United States, anymore than West Germany faces a choice between the Soviet and the United States.

Objects of curiosity

I find it interesting and I believe it is significant that the denunciations are always of United States “imperialism,” not of United States capitalism. The propaganda is against American activities abroad, not of her economic or social or political system at home. And whatever the content and purpose of the pervasive propaganda here it is not directed against Americans or Europeans as such.

It is just not true that Chinese children are being brought up to hate foreigners or foreign nations with different systems. In any of our walks or drives through Peking, Shanghai and Canton we were certainly the object of frank and open curiosity.

But in Shanghai especially the warmth was overwhelming. And to the hundreds upon hundreds of children who seemed to materialise wherever we went, we might well have been Americans or any other foreigner. All they knew was that we were white foreigners and they reacted with anything but hatred.

Our own fears of China in Australia, and I assume Japanese fear of China, are based on the potential strength of a highly organised and disciplined nation of 700 million inspired by a militant doctrine of international revolution.

Only a fool would dismiss these fears out of hand, just as only a fool would ignore the existence of a quarter of the earth’s people. But our great mistake in western policy since the war has been to base all our policies on fear unqualified by knowledge. Thus we have created the very conditions by which our worst fears are realised. MacArthur nearly did it in Korea. It has certainly occurred in that way in Vietnam.

I have said that the second thing to understand about the Chinese is that they are Maoists before they are communists. The cult of Chairman Mao embodies all that we as Australians and Westerners would find most repellent in Chinese society.

Beyond politics, ideology

It is something almost beyond our comprehension, particularly if we view it only as a political phenomenon. It goes beyond politics. It goes beyond ideology. It is something that has taken deep hold upon the Chinese spirit. It is of the very essence of what is happening – the good and the bad – in China today.

The religious element is unmistakeable. I confess that when one sees a group of beautiful children lustily performing a scene from the repertoire of so-called revolutionary opera and ballet, one is torn between admiration for the charm and vigour with which it is done and apprehension about the meaning of it all.

Yet in the international context, the apotheosis of Chairman Mao has its advantages. Communism under Mao is becoming more distinctively Chinese and less and less international. The appeal of communism is its alleged universality. The appeal of Mao is to the Chinese.

And the system he has built in China is for the Chinese. It is a complex organisation with deep roots in Chinese history, Chinese methods, the Chinese character an dthe Chinese mind. Had it not been, its success could not have been so quick and so complete. And the only country in the world where all the necessary conditions apply is China.

Maoism is not really exportable. Nor does Chinese pride – this great, if not the greatest, motivating force in China today – require that it should be exported.

Chinese pride absolutely requires that the revolution China has created should succeed in China. Yet equally Chinese pride inhibits her courting failures in other countries of great dissimilarity. There is good reason to believe that this realisation is behind the statements of Premier Chou En-lai about peaceful coexistence with countries of “different political and social systems.”

All the talks – private and public – I have had convince me that this is a genuine and deliberate policy on the part of the Chinese. They are deliberately placing limits on their world role.

I believe two factors are at work behind the desire of China for an opening to the West of which our invitation was one sign. There is a greater self-confidence in the results of the Revolution, yet a greater awareness of China’s actual limitations. The realisation that the Chinese system is unacceptable and unattractive tonalised into a view that pending the ultimate verdict of history, China will let all countries work out their own destiny and concentrate on perfecting her own revolution. This amounts to a virtual abdication of any role as the leader of international communism at least in the developed countries.

In such countries, the appeal of the Chinese system developed countries is ratiofails at the most fundamental level – the trade unions.ii The Cultural Revolution destroyed any vestige of trade unionism in China. A strike is inconceivable. It is plain that trade unions as we know them have ceased to exist. There are no national trade union organisations in China.

The Chinese Government now speaks of appealing to the people over their national governments. I do not believe that this means an appeal to revolution. The Chinese know that such an appeal is doomed to fail. It is really an appeal for understanding.

Hence the concept of “people’s diplomacy”. Undoubtedly our invitation to go to Peking was part of that diplomacy. So was the admission of a very representative group of Australian journalists. So I suppose was the public meeting with Premier Chou En-lai. If this is what Mr McMahon was referring to in his spiteful little outburst last week he is welcome to his satisfaction.

Of course Chou En-Lai was trying to advance the interests of China, just as we are trying to advance the interests of our country. We are politicians and we each knew exactly where the other stood.

I regard our mission as successful. To put it at its lowest, it achieved everything possible for a group with our status – an opposition from a non-recognising country. Dr Patterson brings home information that, given the slightest degree of common sense on the part of the Australian Government, should prove valuable to our exports, and not only our wheat farmers.

However, the real test of the success of our mission lies not with us but with the Australian people. It all depends upon whether Australia is mature enough and self-confident enough to face squarely the facts of life in our region.

The really serious aspect of Mr McMahon’s outburst is that it rehashes all the old slogans which passed for foreign policy in the fifties and sixties. We must either grow up or fossilise, and Mr McMahon last week spoke for the fossils.

There is nothing within my power I would not do to help reduce the risks of war between China, Japan or the United States. The prevention of such a war – needless, inconceivable, cataclysmic – is the central tasks of statesmanship in our region. The associated task is to realise the living standards in the region. They are interwoven issues. There is no issue involving China, Japan and the United States which is incapable of settlement given a minimum of common sense and goodwill. This mission was an exercise in common sense. I hope it has been some contribution towards goodwill.

-

During his 1971 trip Gough Whitlam filed a series of articles for The Australian about what he saw, and why he believed so passionately in the need for Australia to develop a relationship with China. They are remarkably resonant today.

Read them here:

Whitlam’s Dateline Peking: Labor’s leader reports from China

-

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout