Whitlam’s Dateline Peking: Labor’s leader reports on his trip to China

I suspect that from the moment we stepped into China, our intentions, motives and calibre were being summed up. There was warmth but there was wariness.

Gough Whitlam reports on his historic trip to China exclusively in The Australian, July 11, 1971.

I am now convinced that Australia has it in her power to play an independent role of immense significance to our region’s welfare and our own future.

I say this in no spirit of euphoria because of our reception in Peking. The visit has not changed my basic perspectives or priorities. But it has added to my perception of the initiatives open to a middle power like Australia in an area which has become the focus of competition and confrontation among the four greatest powers.

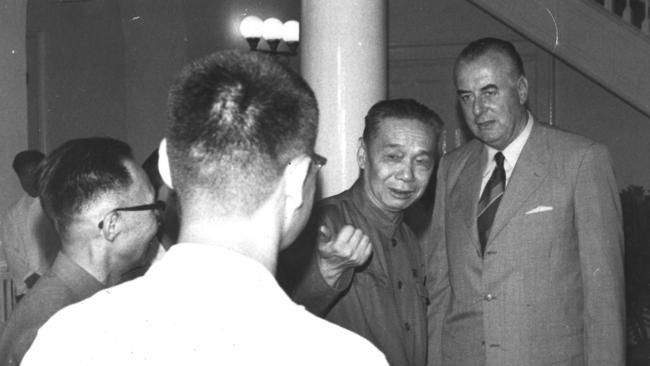

From the first it was plain that the Chinese were taking this mission seriously. I suspect that from the moment we stepped into China at Shumchun, our intentions, motives and calibre were being summed up. There was warmth but there was wariness. And not surprisingly. A generation of mutual incomprehension is not to be dissipated overnight or in a visit of two weeks for that matter. But the first step has been taken.

I think a decisive moment for the success of this mission came at midnight on Saturday, July 3, when we reached Peking, travel-worn after a five hour flight from Canton through a quite spectacular lightning storm. Our hosts of the Chinese People’s Institute of Foreign Affairs gave us the option of a break on Sunday. But from the beginning of our first meeting with the Acting Foreign Minister it was clear that the Chinese had no intention of wasting their time or ours in pointless propaganda.

We had some misgivings on this score. Propaganda is pervasive here, particularly in the Canton area, which is as far as most Westerners get. The eye and the ear are under constant appeal. But very quickly it becomes just an accompaniment and not an affront. No official, high or low, has made the slightest attempt at propaganda.

Chairman Mao is omnipresent. Revealingly, a guide at the Peasants’ Institute in Canton – where Mao lived and worked with his first cadres in 1926 – called it one of the sacred places of the revolution. The reverence for Mao goes well beyond the respect normally given even to so extraordinary and authentic leader of his people.

Yet at our meeting with Chi Peng Fei, an extremely relaxed and assured man in his 60s, the only direct reference to Chairman Mao was my own when, at the end of our 2½-hour talk, I requested that our respects be passed on. There were routine references to United States imperialism and the harshest word for the Australian Government was that it had acted as the accomplice of the United States in Vietnam. When one realises the depth of feeling here about Vietnam, and indeed the genuine fear it has aroused, particularly in the Canton area, one must regard this as relative moderation. I have known, for example, Swedish ministers to be infinitely more severe in their strictures, though Mr Anthony’s remarks at home about selling our soul have bitten deeply with probably the proudest and most sensitive people on earth.

But the crucial question in our diplomatic relations is Taiwan. The Australian Government’s position there seems to me to present insurmountable barriers against the restoration of normal relations. I think it is significant that Chinese leaders usually refer to Chiang Kai-shek when they refer to Taiwan. They refer not so much to the issue of Taiwan but to the problemof Chiang Kai-shek.

I would guess that they see a political settlement after his death as a real possibility. It should be stressed here that even the present Australian Government has no military commitment to Chiang Kai-shek or his regime on Taiwan. I have been emphasising this here in all my discussions. It would be inconceivable for any Australian Government to enter into such a commitment.

My belief that an Australian Labor Government can negotiate on the basis of the Canadian formula was confirmed by a striking omission in my long, wide-ranging and public conversation with Premier Chou En-lai. In fact he did not raise Taiwan. Yet equally, his entire conversation was based on the clear assumption that the return of a Labor Government in Australia would mean the immediate resumption of normal diplomatic relations. In all our previous talks with the Foreign and Trade ministers, Dr Patterson and I made it clear that what we proposed was the application of the Canadian formula which takes note of the Chinese position on Taiwan. I do not believe for a moment that Premier Chou’s omission was accidental. He is too skilled to make errors of that kind and he plainly had been completely briefed on what we had said to the other ministers. With a man so deliberate in his mind and clear in his purposes, one must place as much significance on what he omits to say as on what he does say.

Never accept two Chinas

All ministers saw the Taiwan question as the chief stumbling block against improved relations with the United States.

Mr Chi said it was the crux. “If that could be settled we would certainly consider relations with the United States” he said.

There is no possibility whatsoever that China will ever accept the so-called “two Chinas.” Taiwan to them is a province of China and there is only one China.

I accept this as the only view China could maintain with dignity. To them it is incidental that Chiang Kai-shek happened to make his last citadel on an island. Indeed, it is only because of that accident in military history that the Seventh Fleet has been able to shield him.

Suppose a different military result in 1949 had enabled Chiang to hold out in a province on the mainland. There would then be no question of military support from the West, nor would we seriously question the basic right of the Chinese Government to assert its ultimate sovereignty over such a province. We would just shrug off his final defeat as the last act of the Chinese civil war. I would hope that the removal of Chiang Kai-shek by the processes of nature will enable the United States to take a fresh look at her position on Taiwan.

The Americans are every bit as concerned with saving face as the Chinese. We call it honour. If the United States believes that it owes a debt of honour to Chiang Kai-shek – though what except harm he has done to the United States I cannot imagine – the debt will only be cancelled by Chiang’s eventual departure. The important consideration is the people of Taiwan.

They have never been consulted about their future. But it would be a tragedy of grotesque proportions if the United States were to drift into the same untenable and ultimately undischargeable obligations in Taiwan as in Vietnam.

Before we sloganeer ourselves into any impossible stances on Taiwan, the West should recall that already we have transferred the people without the slightest reference to their wishes. Roosevelt and Churchill decided at the Cairo conference that they should be transferred to Chiang from Japan when the war ended. The decision was justified on the ground that Taiwan was an integral part of China. How inconvenient for us that the Chinese now make this same claim.

Taiwan excepted, I did not detect the depth of animosity towards the United States that I would have expected. This came out in the very persistent questioning with which Chou En-lai probed our attitude to ANZUS. I have no doubt that he would have liked a general denunciation of the United States as distinct from our particular criticism of her policies in Indo-China. But he was clearly familiar with Labor’s platform on ANZUS, and even knew the changes made in it as recently as the Launceston conference.

It seemed to me that Chou En-lai was more sceptical about ANZUS than hostile towards it. He drew a parallel between ANZUS and the Sino-Soviet treaty of 1950, but as a lesson he thought we should learn, not as a threat: a warning from their experience, not as a menace to us. I was able to make the point that our relations with the United States had not deteriorated in the way that China’s relations with the Soviet had. He did not dissent.

It is especially in China’s attitude towards the Soviet and Japan that one learns to draw the distinction between the Chinese as Chinese and as communists. The Chinese experience, more than the Chinese ideology, determines her attitudes towards her neighbours.

Australia as peacemaker

In this, I believe, lies Australia’s real opportunity. If we can adopt a posture of influence with, but independence of Japan and the United States, we can have a positive role in improving relations between all three powers. Our relative smallness becomes a positive advantage.

This is especially true in our relations with China. There is nothing China can fear from us. We have no power as a nation to humiliate, much less harm China. Nothing in our possible trade relations could ever induce in the Chinese any uneasy sense of dependence upon us.

Yet our resources and skills give us a significance and influence out of all proportion to our size. So do our trade relations with Japan and our treaty relations with the United States.

Few countries can do as much to moderate hostile and counter-productive reactions in Japan and America. And I now believe that few can do as much as Australia to moderate Chinese fears if they can be shown to be unfounded. But they must be shown to be genuinely unfounded.

Chou En-lai asserted that the United States and Japan were currently discussing the supply of tactical nuclear weapons to Japan. I pointed out that this would be in clear breach of Japan’s treaty undertakings. He was not impressed. But it would be impossible to conceive a more foolish and retrograde step. It would merely confirm the worst fears of the Chinese.

China’s fears of Japan

It would be taken as incontrovertible proof of revived militarism. It would reinforce to an unshakeable degree China’s conviction that it is being encircled by the Soviet, Japan and the United States. It would destroy any hope of a détente with China. It would revive the spectre of Dullesism. And it would be military pointless and counter-productive. I could think of no step which would take us more surely along the road to a third world war.

One of the great troubles in relations between China and the West is that we expect China to believe the best about our statements of intention while we choose to believe the worst about hers. We expect understanding for our own fears, but we have never tried to understand hers. We have been obsessed by our own historical experience, but we scoff at China’s obsession with her own experience.

We saw nothing strange in an American president justifying the war in Vietnam by drawing a parallel with Munich. We saw nothing strange in a British prime minister drawing the same parallel over Suez. The two greatest Western debacles since the war both originated in the conviction by statesmen that we had to learn the lesson of Munich about the consequences of appeasement. For Lyndon Johnson and Anthony Eden World War II was their central experience.

We understand this type of historicism in ourselves. We can even understand it in the case of the Russians. We make proper allowance for their fear of revived German militarism. Only to the Chinese do we deny the luxury of learning by experience or of basing policy on the lessons as they see them of their own history.

I hope to be able to say more in my next article about our future trade relations with China when Dr Patterson has completed detailed discussions with Chinese officials. Our central conclusion is that trade and diplomacy cannot be separated.

To put it crudely, the Canadians have stolen a march on Australia. This adds point to our concern here about the curious remarks being attributed to Mr McMahon.

Why he should have chosen this particular time to say that diplomatic relations with China appeared very far off is beyond our comprehension. He is reported as saying that he has been unable to get any sense from the Chinese on his expressed wish for a dialogue between the two governments.

All I can say is that it is very easy to get a great deal of sense from any men here with whom one is prepared to deal frankly and seriously. The Chinese do not confuse rhetoric with negotiating. We are convinced that when normal relations are restored, Australian businessmen will be able to talk and negotiate on a completely rational basis.

During a century of Western intrusion and domination, the Americans believed themselves to be the very special friends of China and they believed that this feeling was reciprocated. When China became communist at the height of the Cold

War the Americans experienced all the pangs and resentments of the rejected lover. John Foster Dulles in particular felt the Chinese Revolution as a personal affront and in this over-reaction lay the roots of the war in Vietnam.

In fact, the Chinese have made no attempt to seduce us. As I have said, there has been great anxiety on both sides that this visit should be both pleasant and successful. But even Senator Gair may be assured that our virtue remains intact.

My general impression is that the Chinese are so convinced of the logic of their position that simply for it to be stated is for it to be understood. In specifics and details I have found the Chinese as frank and realistic as any officials I have spoken to in any country in the world, and better informed about Australia than most. And, knowing our position already, they accept it as they expect us to accept the sincerity of theirs.

-

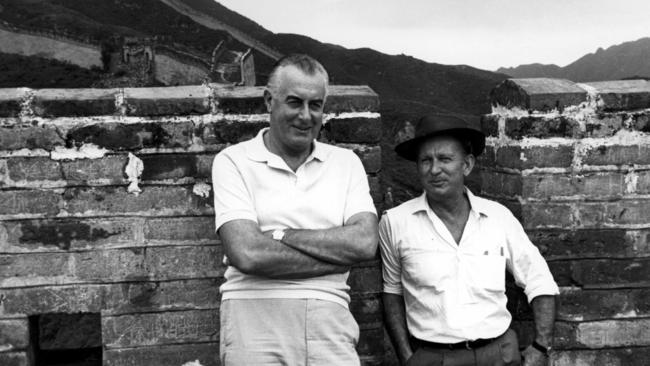

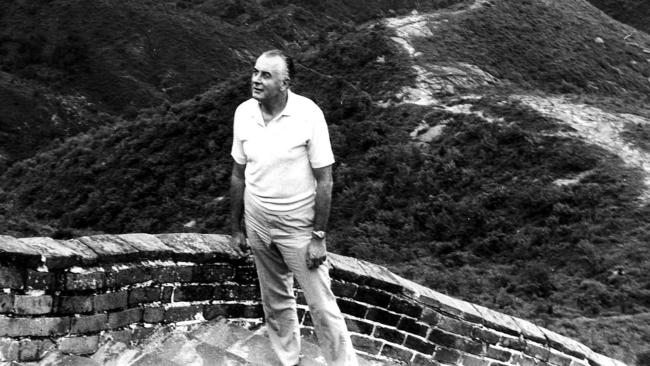

During his 1971 trip Gough Whitlam filed a series of articles for The Australian about what he saw, and why he believed so passionately in the need for Australia to develop a relationship with China. They are remarkably resonant today.

Read them here:

Whitlam’s Dateline Peking: Labor’s leader reports from China

-

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout