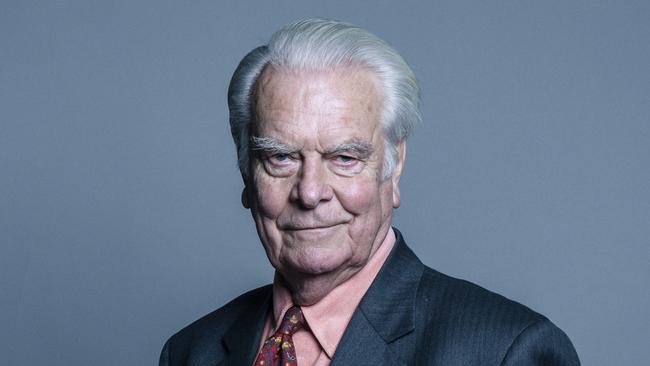

Ex-Foreign Secretary David Owen on what to expect from PM Keir Starmer

David Owen, who left Labour in the ’80s as it veered left, is full of praise for the new leader.

When the so-called “Gang of Four” former Labour ministers formed the Social Democratic Party in March 1981, after the ultra-left had taken control of the party, it was a seismic event in British politics. Now, with the Labour Party set to return to power next week, Gang of Four member and former foreign secretary David Owen believes it has finally become what he always wanted – a moderate, centre-left party.

“It is now more a social democratic party,” Lord Owen, 85, tells Inquirer over Zoom. “That’s why I felt forced to leave Labour and to create a new party, but it was never to be anything other than on the centre-left. It was social democratic. Labour seems to me to have come around to that view. We don’t get much credit for that. But that’s politics.”

Owen is one of the giants of UK politics. He served in the House of Commons (1966-92), was a minister under Harold Wilson (1968-70; 1974-76) and Jim Callaghan (1976-79), and SDP leader (1983-87). He has been in the House of Lords since 1992. With intellect, charisma, style, and a touch of arrogance, he was regarded as a future prime minister – until he broke with Labour.

“Labour is going to win the election,” he declares. “It is a typical example of when a political party has been out of office for a very long time, there is a swing and a definite swing, and it’s a gut feeling of the general public. The one thing Labour has is to say ‘kick the buggers out’.

“In many ways, that’s the best definition of politics. You’ve got to be able to remove these guys. The Tories have been in too long. You need the new party coming in. You need the alternation of power. It’s the only thing the electorate have, and they want to take the Tories out and try Labour.”

So what does he expect from a Labour government led by Sir Keir Starmer?

“He has respect from people,” Owen judges.

“He’ll become prime minister with a sense of goodwill towards him. If he acts wisely in his first year, and he’ll certainly have a big enough majority, he is likely to run a full term of four to five years.”

“Possibly a little dull but I don’t think people object to that. He’s a lawyer, and he was for quite a long time Director of Public Prosecutions. He’s used to being faced with a problem, weighing it up on either side, and then coming to a decision. There’s nothing flash about him. Not a firebrand but careful.”

After 14 years of Conservative rule and the revolving-door prime ministership, Labour convulsed by its own internal divisions, and the lingering bitterness over Brexit – which Owen “somewhat reluctantly” voted for – the people are disillusioned.

“Never has there been such a lower support for politicians,” Owen believes.

“They’re awfully fed up. I think that’s reflected in a lot of different issues. We’ve really lost touch. It will it come back, though, these things happen in phases.”

Before being elected to parliament, Owen was a neurologist and psychiatrist at St Thomas’s Hospital in London, on the River Thames. He says it was a good background for politics because it gave him a unique insight into human behaviour.

He developed the “hubris syndrome” theory – an affliction whereby power inhibits judgment – and has written extensively on it. Symptoms include supreme self-confidence, disregarding advice, impulsiveness and recklessness. Those who had it include David Lloyd George, Margaret Thatcher and Tony Blair. He now adds Liz Truss – prime minister for 49 days – to the list.

“There is a tendency among politicians to be vulnerable to hubris,” Owen says.

“The Greeks thought it was a dangerous thing, especially for young people, because they could start making bad decisions if the personality was dominant and facts were secondary.”

He argues most politicians should not stay in power once they reach their 70s, when parts of the brain linked to higher cognitive thinking can degrade. He saw ageing leaders while a minister and followed this up with study. He believes Joe Biden and Donald Trump are too old to seek re-election. “We need to avoid becoming a gerontocracy,” Owen says.

Late one night in mid-1968, Owen was summoned to Downing Street to meet Wilson. He found the prime minister working in the cabinet room. “I want you to become minister for the Royal Navy,” Wilson said. “But, Harold, I’m one of your biggest critics,” he responded. Wilson puffed on his cigar, looked directly at him, and said: “You can’t be now. You can’t be now.”

“I got him wrong in some respects,” reflects Owen. “Wilson always had a sense of humour; there was no snide to him. He didn’t pretend to be more than he was. He had a photographic memory but that was going, and I think that’s what made him retire. He was cunning; he could manoeuvre and manipulate.

“A lot of us who were with Wilson were critical of him when he was in government and became rather soft about him later on, and rather more appreciative of some of his skills. He’s definitely judged by historians more favourably now than when he was in office.”

The high point of Owen’s career was when Callaghan appointed him to the Foreign Office (1976-79). A year later, at age 38, he succeeded Tony Crosland as foreign secretary. Before that, Owen was junior to Barbara Castle in the Health and Social Security Department. He found Callaghan to be a shrewd manager of a cabinet teaming with ambitious ministers and could share power.

“(Callaghan) had held all the great offices of state,” Owen recalls. “So he came to the office of prime minister hugely experienced. He had one underlying commitment: he wouldn’t interfere. If you had an anxiety with him, you could discuss it. He was very acute in human relations. If he had a suggestion, it was very gently put. He could guide a minister without the minister knowing he’d been guided.”

The 1980-81 Labour Party conferences were a turning point for defectors Owen, Bill Rodgers, Shirley Williams and Roy Jenkins. Labour adopted compulsory re-selection for MPs, a leadership election college of unions, party members, MPs, and shifted left on policy, supporting unilateral nuclear disarmament, withdrawal from the European Economic Community and interventionist industry plans.

In January 1981, the Gang of Four issued the Limehouse Declaration which called for “a new start” in politics. The SDP formed an alliance with the Liberal Party and won 25.4 per cent of the vote at the June 1983 election and 23 seats. The two parties later merged to become the Liberal Democrats. Owen thought this was a mistake.

“Roy, a rather smooth character, was hell bent on shifting the SDP into an alliance with the Liberals,” Owen recalls. “But the market research showed the one thing you must not do is blur your image with another party. Well, we went and did exactly opposite. A completely crazy decision.”

Meanwhile, Michael Foot, a left-wing intellectual, had become Labour leader after Callaghan. The 1983 election was a disaster for Labour, saddled with a manifesto that was labelled the longest suicide note in history. Margaret Thatcher was utterly dominant.

“Foot was not fit to be prime minister of any country,” Owen says dismissively. “I knew him well. He was never to be trusted with nuclear weapons. He was basically a pacifist. It was absurd that he believed he could be prime minister.”

In 1983, Owen became leader of the SDP. Labour’s new leader and deputy leader were Neil Kinnock and Roy Hattersley, respectively. They decided to remain with Labour and try to drag the party towards the centre. But the battle between left and right within Labour would go on for a decade.

“The electorate had made up their mind about Kinnock,” Owen says. “He moved to the centre when he became leader but voters were never going to let him be prime minister. He has a lot of public affection now. One of the good things about politics is that people can be unpopular and then become popular.”

Kinnock, John Smith and eventually Tony Blair made Labour viable and the party regained government in 1997. But the mad left were not defeated and reached their apogee when Jeremy Corbyn became leader in 2015.

Starmer, though once a Corbyn supporter, expelled the former leader and returned Labor to the moderate centre-left.

“Corbyn was the most left-wing figure in the Labour Party for many years,” Owen says. “The left have to be fought. If you’re on the left, there’s always a far-left, and they have to be curbed, contained and controlled.”

It was a “wrench” to leave Labour, Owen reflects. There were overtures from Thatcher and John Major to join the Conservative cabinet, and from Blair and Gordon Brown to rejoin Labour. “I’m, basically, still Labour,” he notes. But the moment he left Labour ended any hope he had of becoming prime minister.

Does he ever think it is a job he would like to have done?

“Not too much,” Owen says with a grin. “It wafts across every now and then. Particularly when there is a bad decision by a prime minister, whether Conservative or Labour, and it makes me wonder if it could have been handled in a different way.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout