Britain faces 1970s-style left-wing stagnation under Starmer’s Labour

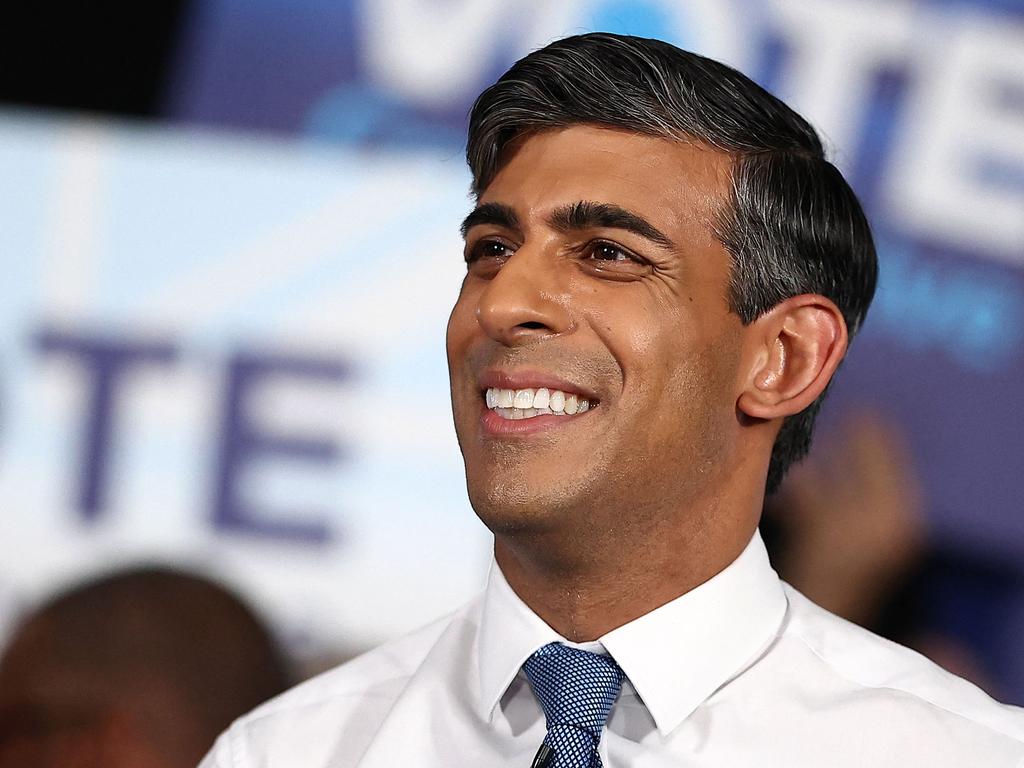

The Conservatives under Rishi Sunak are set to suffer their worst defeat since Tony Blair walloped John Major in 1997. Enter Sir Kier Starmer – the UK’s Albo – who will eventually lead the most left-wing government in British history.

It will start with reassuring fiscal and strategic rhetoric but will drift further and further left because that’s where the party is, that’s where its activists are and that’s really its leader’s disposition.

Because Britain’s financial position is so much worse than Australia’s, it will more quickly lead to crisis, or at least renewed stagnation and alienation.

The Conservatives under Rishi Sunak will suffer their worst defeat since Tony Blair walloped John Major in 1997. With a swing just on 9 per cent, Labour went from 271 seats to 418, the Conservatives from 336 seats to 165, their worst loss since 1906.

The Conservatives could do even worse this time. The latest YouGov poll has Labour on 47 per cent and the Conservatives 20 per cent, a staggering 27-point lead.

Polls do vary; one outlier has the Tories just 12 points behind. The Times’ poll of polls puts the overall Labour lead at 21 points to 23 points, depending how undecideds are allocated. If that holds, the Conservatives could win just 138 seats and Labour 447, a bigger margin than 1997. So the campaign will be everything, and it has started off as a train wreck for the Conservatives.

Something like 80 Conservative MPs have decided not to contest their seats. There’s already intense jockeying going on over the leadership of a reduced party. Should the Conservatives come hurtling back to competitiveness and Labour significantly underperform expectations, even if it wins a pretty big victory, some think former prime minister David Cameron could come back as leader. He’s currently Foreign Secretary and a member of the House of Lords. If he really thinks the Conservatives have a shot at regaining power in one term, he might run. That’s unlikely but not to be ruled out altogether.

Assuming the Tories are massively hammered, the priority will be consolidating their base as a platform to at least move forward in five years. The base now is voters 65 and older. The stripling over-50s are more inclined to vote for the more radically right-wing Reform UK party, founded by Nigel Farage but led in this election by the anonymous Richard Tice.

Reform is polling 12 per cent. If the Tories could get most of that back, and add just a little bit from here and there to their existing 20, they might get up 30 or 32 per cent. That would be a triumph.

Consolidating the Conservatives as the dominant party of the centre right could prove the big task over the next five years.

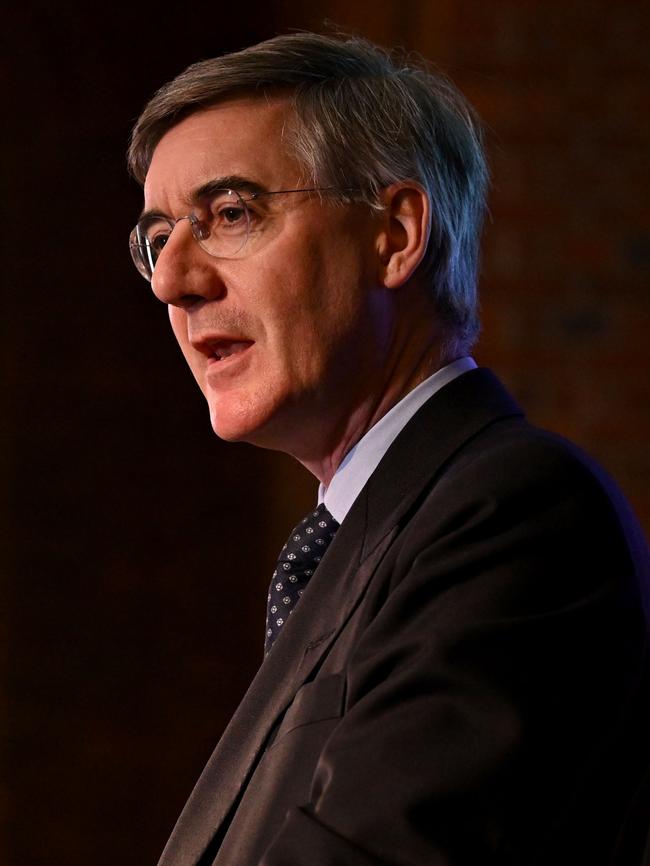

Jacob Rees-Mogg could be a Peter Dutton type candidate, a genuine Conservative, plenty of experience, a thick hide, credibility with the faithful and more agile in hand-to-hand combat than he’s given credit for.

I’ve interviewed Rees-Mogg half a dozen times. He’s smart, witty, secure in his own skin. His slightly eccentric celebrity, though not fake, is, like that of Boris Johnson, studied, practised, knowing. Under Johnson, there was perhaps room for only one highly entertaining Conservative identity. Rees-Mogg could hold the Conservative base, manage a disputatious party and make Labour pay for mistakes. But that’s all speculative just now.

Former home secretary Suella Braverman is tough on illegal immigration and law and order, and a bit of a hero to the right. She’s of Indian background. Business Secretary Kemi Badenoch, of Nigerian background, more personable than Braverman, is also a darling of the Right, being outspoken on culture wars issues. Because they come from ethnic minority backgrounds Braverman and Badenoch excite almost demented hatred on the left, as though somehow being Conservative means they’ve betrayed their race.

Nonetheless, for Conservatives to move beyond their elderly core vote, they need votes from ethnic groups not automatically hostile to them – Indians, other Asians, some Africans. Many are more religious, more socially conservative, than the background Anglo population.

The battle with Reform for the Tory heartland may be one reason Sunak went so early. Sunak was expected to call an election around November. Normally a government this far behind postpones an election while it works feverishly to regain support and hopes something bad happens to the other side.

But there was talk of Farage coming back to lead Reform. The Conservatives fear Farage. Johnson and Farage are the two most influential conservatives of the past decade. Reform doesn’t seem yet fully on an election footing. Farage is making too much money as a trans-Atlantic commentator, ideological provocateur and friend of Donald Trump to come back and slog through British parliamentary politics, even if he could win a seat.

Sunak may also have thought with inflation easing a bit, and economic growth weak but at least positive, this was the least bad time to go.

Further, the Conservatives have so far made a mess of implementing the Rwanda solution, which is modelled on Australia’s offshore processing scheme. Under the Rwanda solution, anyone who enters Britain illegally and claims asylum would be sent to Rwanda for processing. If found to be a genuine refugee, they could be resettled in a third country or stay in Rwanda.

Sunak has been ineffective in implementing this. His government was thwarted by the courts and even as he passed legislation to override the courts the European Convention on Human Rights would probably have vetoed the scheme. Britain would then have had to leave the ECHR. Most Tories would have rejoiced but some would have rebelled. Cue more stories of government split.

So Sunak decided to short-circuit all that and go early, presumably not thinking he can win but he might save the furniture – what some are calling the Dunkirk strategy.

It’s astounding the Conservatives have fallen so far from public grace after Johnson’s slashing win and 80-seat majority in the 2019 election. Johnson himself is one of the great tragedies of modern Western politics. He is surely the verbally cleverest and most charming man I’ve met, with a prodigious ability to project himself into the centre of public consciousness.

He was Britain’s loveable rogue and won election after election, twice as London mayor and then as prime minister. He and Farage are the two individuals responsible for Brexit. Johnson’s fatal flaw was an absolute lack of personal discipline. He was destroyed by Covid, by a lack of clear policy, but more by his personal breaking of stifling rules his government imposed on everyone else.

His government couldn’t deliver the promise of Brexit. Instead of taking advantage of Brexit freedoms to unleash the economy’s animal spirits, Johnson massively increased spending and let bracket creep increase income tax. The Conservatives have been in office for 14 years since 2010 and taxation now accounts for more than 40 per cent of GDP, the highest proportion since the early days after World War II.

All this government spending inevitably produced high inflation and interest rates. A two-year fixed mortgage rate is now near enough 6 per cent. The budget deficit is more than 4 per cent of GDP. Economic growth is an anaemic 0.5 per cent.

Nor did the Tories ever get control of immigration, either legal or illegal. A key complaint about the EU was that it prevented Britain controlling immigration. But since Brexit immigration has boomed, even as the government constantly promises to reduce it. I’m generally a pro-immigration person, but in any country a particular immigration level can be too high. I’ve asked a series of Conservative ministers over the last couple of years why they can’t simply cut immigration by refusing to issue more than a certain number of visas, imposing an effective cap.

I’ve never got a real answer but it seems employers, universities and the usual suspects who just want more all the time, plus weirdly designed immigration categories which are effectively demand driven, have been too much for the government to overcome.

The Tories didn’t really deliver on any of their key priorities. When they came to office, defence spending was 2.48 per cent of GDP. Johnson was a great supporter of Ukraine, and of Israel, as were his successors, Liz Truss and Sunak.

But now, after 14 years of Conservative government, with Russia waging war on Ukraine and NATO Europe in more danger than at any time since World War II, defence spending is down to 2.28 per cent of GDP. The British Army, 150,000-strong at the height of the Cold War, is scheduled to be 73,000 by 2025, the smallest size since Napoleonic times.

Sunak now says building up Britain’s defence is a high priority. But voters judge a 14-year-old government on what it has done. The first big policy initiative was Sunak’s promise to introduce 12 months of compulsory national service, in the military or community activities, for young people. This is good policy, but I should think effectively impossible to implement in today’s surly, polarised, ideological environment. Sunak hopes it will play well with the over-65s.

Similarly, he wants to abolish one in eight university degrees, which he rightly describes as useless, and use the money for apprenticeships. That’s excellent policy but, as with the national service idea, there has been not a speck of preparation for it.

The Conservative campaign launch was a shambles. This surprises me because, having interviewed and met Sunak on a number of occasions, what impressed me most was how precise, courteous, well organised and disciplined he was.

Well-placed sources suggest Conservative campaign headquarters was against the early election. Sunak, fearing resistance from cabinet colleagues, told almost none of them what he had in mind. Then, having seen the King, he rushed out when the weather was overcast and the clouds promptly burst. None of his staff had the wit to bring him an umbrella.

Sunak is likeable, plausible, personable, cheerful, hardworking. He will campaign his heart out. He might yet be able to recover some ground. If the Tories win less than 100 seats, their position as one-half of the governing parties in Britain will be under real threat, while 200 would be success.

The British state has grown vast under the Conservatives, but it’s ineffective. There are six million people on the National Health Service waiting list needing operations, scans or procedures, waiting many months. British survival rates for cancer patients compare poorly with other developed nations.

The Tories took extreme measures against climate change, massively increasing energy costs for little environmental benefit. Johnson, influenced by his new wife, eccentrically embraced animal rights.

As with the last years of Major, there seems a never-ending succession of Tory sex scandals and internal divisions. Its time seems up.

Which brings us back to Starmer’s likely government. Starmer was director of public prosecutions and knighted before he entered parliament. Sunak and Starmer share in common having had substantial jobs before politics. Starmer was for a while involved in Trotskyist student groups.

He served in Jeremy Corbyn’s shadow cabinet but was soft left in contrast to Corbyn’s hard left. Starmer is competent, calm, methodical, orderly and free from scandal. He is supremely dull, but that may be agreeable after the Tory drama and chaos.

Starmer is exceptionally ruthless. Corbyn’s leadership was one of the most bizarre episodes of modern politics. He was elected by radical activists among Labour’s rank and file. Although very, very far left, Corbyn for a while enjoyed an anti-establishment popularity.

Corbyn tolerated disgraceful anti-Semitism in Labour. When Starmer took the leadership in 2020 he set out to purge the Labour Party of anti-Semitism and of Corbyn followers.

So why do I say that Starmer will eventually lead the most left-wing government in British history?

Starmer declared, at the beginning of the campaign, that he’s a socialist and a progressive. Though he has moved the party back to sanity after Corbyn’s madness, he himself is well to the left of Blair or Gordon Brown.

His ruthlessness is promising. He has barred a number of Corbyn loyalist MPs from running for the Labour Party and the campaign began with great controversy over whether the party would allow close Corbyn ally Diane Abbott to run for Labor. Abbott had been suspended from the party for writing a letter saying that Jews endured only mild prejudice comparable to that suffered by redheads.

Abbott claimed she would be prevented from running. Starmer said no decision had been made. It seemed clumsy but astute insiders think Starmer was happy to have this public brawl with a notorious and unpopular far-left politician, (though she enjoys the iconic status of being Britain’s first black female MP). For Starmer, this kind of conflict helps define him as more Blairite than leftist. But the public hasn’t fallen in love with Starmer, as they did with Blair.

Starmer is going to face prodigious difficulties and unsolvable contradictions as prime minister. The junior doctors committee of the British Medical Association has decided to go on strike immediately before the election to support their demand for a 35 per cent pay rise. The expectations on Labour from its own supporters for pay rises, expanded social services and expensive industrial policy will be huge.

But there simply is no more money. That’s why I think Starmer will follow the Albanese experience. He’ll win a big majority, unlike Albanese. The Greens are not eating a huge chunk of his vote on the left, unlike Australia.

Like Albanese, Starmer will speak in moderate, reassuring, sensible tones. He’ll go along with AUKUS, though that could be threatened on the left eventually. Albanese expressed admiration of John Howard and promised strong action on defence. But he has spent like Gough Whitlam and done nothing on defence.

Starmer starts off well to the left of Blair. And he commands a party that twice elected Corbyn as its leader. The Labour Party is notoriously ill-disciplined. Even with government in its grasp, 55 MPs crossed the floor early in the Israel-Gaza war to back a more anti-Israel motion than Starmer would allow.

Numerous local councillors were recently elected in Britain on a platform of giving a voice to Gaza. Starmer’s wife is Jewish and his children are being raised in the Jewish religion.

The last census showed four million Muslims in Britain. The number would be larger now. They are almost all Labour voters, many are Labour activists, almost all are anti-Israel. This whole huge pulsating force within Labour has little respect for Starmer.

His party expects huge improvements in the NHS. Starmer has vowed to cut NHS waiting lists radically by increasing evening and weekend consultations. This will be hugely expensive.

As Britain’s population gets older, frailer and sicker, suffering many lifestyle diseases, the demands for transfer payments and expensive government services are endless and rising exponentially.

Starmer’s government, like Albanese’s, will act to entrench union power and favour unions. Public sector unions, teachers, nurses, civil servants, will get favoured treatment.

Britain cannot continue credibly with current defence expenditure, but there’s no room for new money. On all cultural issues, the radical activists now dominate within Labour, as they do in virtually all centre-left parties around the world. But millions of ordinary Brits hate woke culture politics.

There will be an initial burst of goodwill for Starmer, then a long slow burn, or perhaps a fast burn, to renewed crisis. Britain in the 2020s may come to resemble Britain in the pre-Thatcher 1970s – stagnation, stagflation, strikes and silliness. But today’s world is much more unforgiving than the 1970s.

The Labour Party will win a crushing victory in the British election on July 4. Sir Keir Starmer’s government will resemble Anthony Albanese’s in Australia.