Jeremy Corbyn was our biggest mistake: Neil Kinnock

As centre-left parties the world over face existential crises, Neil Kinnock says there’s a long way to go for Labour.

On a cool grey day in north London, as the coronavirus lockdown gathered pace, I knock on Neil Kinnock’s door. The former Labour leader offers me a warm welcome, takes my coat and brews a pot of tea. In the kitchen, surrounded by family photos, Glenys Kinnock tells me her husband has always been quite the gentleman.

A half-century ago, Kinnock made his name as a devoted socialist, combative political activist and compelling orator. He was born in the industrial southeast of Wales, the son of a coalminer and a nurse. Labour values pulsated through his veins.

In the wake of Labour’s worst election defeat since 1935, Kinnock guards against despondency. “I take refuge in rage,” he says.

Kinnock’s leadership of the Labour Party (1983-92) was marked by an internal struggle over policy and organisational modernisation, and a battle against the breakaway Social Democratic Party. Labour almost won the 1992 election. He saved the party and paved the way for Tony Blair’s victory in 1997.

History has turned full circle. Jeremy Corbyn was a throwback to the militant left that Kinnock liquidated decades ago. Labour has again been riddled with divisions and riven with hatreds. Its future is still uncertain. An overhaul of the party organisation and its policies is a priority for new leader Keir Starmer, just as it was for Kinnock generations ago.

“The fundamental thing that went wrong was electing Jeremy Corbyn as leader,” Kinnock, 78, says. “He is an unreconstructed Bennite. What we’ve seen is what would have happened to Labour if Tony Benn had taken over, even though he was a man of much greater intelligence and capability than Corbyn.

“The absolute inexcusable ineffectuality in dealing with anti-Semitism. Anti-Semitism in the Labour Party! Bloody hell, it’s a sentence I thought I would never have to employ. And the superficiality and use of slogans in place of real policies. The manifesto was packed with promises for everybody. People still believe in the spirit of Christmas but not in the Tooth Fairy.”

Kinnock, from the soft left, fought a bitter battle with the hard left. In 1985, he savaged the Trotskyist Militant Tendency at the party’s conference in Bournemouth. Corbyn defended Militant in the 1980s. Momentum, which provided Corbyn’s support base, is the modern equivalent of Militant.

“There are a lot of smart youngsters in Momentum and they have been ruthlessly exploited by the remnants of the outer left from the 1980s,” Kinnock says.

“I thought I’d killed them off. They did go away for 30 years and came back not one bloody millisecond wiser. There is a new generation who are learning the hard way that personal enthusiasm is not a revolution.”

Kinnock also was enthusiastic about social and economic change when he was elected to the House of Commons 50 years ago on June 18, 1970. He was just 28 years old and had worked for the Workers’ Educational Association. He was animated by the idea that parliament could be an instrument for justice. “I realised that if people like us were going to advance it would have to be done collectively and through the process of democratic representation,” he explains. “You couldn’t do it by prayer or by force or by wealth — there was only democracy.”

Kinnock remembers as a teenager seeing Harold Wilson, Aneurin Bevan and Michael Foot share a platform at the Tredegar Workmen’s Hall. Foot was fiery and direct. Bevan was considered and poetic. Wilson’s lecturing style was punctuated with jokes. Wilson was the party leader and outgoing prime minister (1964-70; 1974-76) when Kinnock was elected to parliament. “Wilson didn’t wield the power he got with a big majority to make the party sing from the same hymn sheet — loud, strong and proud — and he was overtaken by prime ministeritis,” Kinnock reflects. “He was not as forceful, with his intellect and political command, that he could have been. And the result was I got elected on the day he got defeated.”

James Callaghan succeeded Wilson and served as prime minister until 1979. Kinnock was closer to Callaghan. “Jim always had a chip on his shoulder about not going to university and therefore not being intellectually equal with the people that he led, and this meant he wasn’t as strong as he could have been,” Kinnock says.

In 1980, Callaghan resigned as party leader and Foot was persuaded to run for the leadership. Foot was admired for his erudition and kindness but was past his prime. Kinnock did not think Foot should nominate but nevertheless ran his campaign.

“Damn it we won,” Kinnock says with a laugh. “I told a lot of lies to get him elected and condemned Michael to three hellish years as leader. But the reason we still had the Labour Party in 1983 was Michael Foot and his huge courage and generosity.”

Foot had a torrid time. Roy Jenkins, David Owen, Bill Rodgers and Shirley Williams — the “gang of four” — resigned to form the centrist Social Democratic Party. Labour moved to the left and promised renationalisation of industry, higher taxes and more spending, abolition of the House of Lords, unilateral nuclear disarmament and exiting the European Economic Community.

MP Gerald Kaufman labelled it “the longest suicide note in history”. Margaret Thatcher trounced Foot at the 1983 election.

Kinnock succeeded Foot as leader. Roy Hattersley, from the right, became deputy leader. Kinnock had impressed during the campaign. He gave a powerful speech warning of a re-elected government. “If Margaret Thatcher wins on Thursday, I warn you not to be ordinary, I warn you not to be young, I warn you not to fall ill and I warn you not to grow old,” he said. Another turning point was opposing Benn’s challenge to Denis Healey as deputy leader in 1981. Kinnock abstained from the vote, which Healey won by just 0.4 per cent, and organised other MPs to do the same. “It stopped the advance of the simplistic self-indulgent left,” Kinnock says. “It didn’t cost me any friendships but it changed perceptions of me. I now wish I had voted for Denis.”

The new leader purged the party of extremists, moved to the centre on policy and modernised campaigning and communications. The red rose replaced the red flag as the party emblem. None of this was easy. Added to all this was the miners’ strike and the belligerence of its leader, Arthur Scargill, which made leading the party difficult in these years dominated by Thatcherism. “Between stopping the party from sinking and trying to rebuild its credibility, and putting up an opposition to Thatcher, it was a huge challenge,” Kinnock recalls. “I didn’t see it as moving the party towards the centre but maximising electability, and that meant divesting us of policy stances which were anathema to the electorate.”

Kinnock also went through a transformation. He sought to tame his exuberance and gregariousness in favour of a more statesmanlike poise. It was not an easy transition and the media amplified his gaffes. His parliamentary performances were mixed and media interviews often stilted. Yet his stirring oratory, like that before the 1987 election, surpassed any of his contemporaries.

“Why am I the first Kinnock in a thousand generations to be able to get to a university?” he asked. “Why is Glenys the first woman in her family in a thousand generations to be able to get to university? Was it because all our predecessors were thick? … Does anybody really think that they didn’t get what we had because they didn’t have the talent, or the strength, or the endurance, or the commitment? Of course not. It was because there was no platform upon which they could stand.”

Labour lost the election but took 20 seats from the Conservatives. Thatcher’s third term, however, was tumultuous and she resigned after losing the support of her party in 1990.

Kinnock had his own internal critics and could be prickly with colleagues. He won a leadership challenge from Benn in 1988. Nevertheless, Labour led the Conservatives in every poll during Thatcher’s final 18 months and was favoured to win the 1992 election. But Kinnock did not expect Labour to win. The Conservative majority of 102 seats was “a hill too steep to climb”, he says. (It was reduced to 21.) Labour had a “residual credibility problem” and the government had jettisoned its biggest weakness: Thatcher.

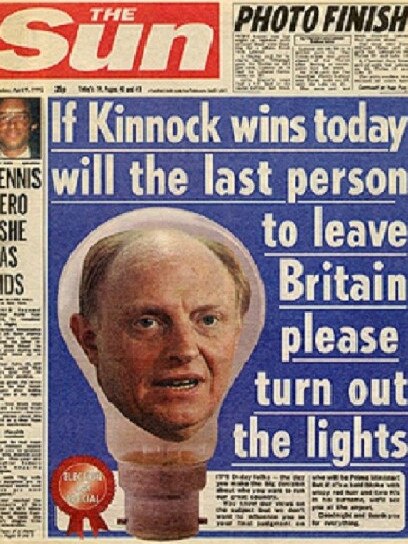

The new prime minister, John Major, was a shrewd campaigner who styled himself as a “man of the people”. He won the backing of The Sun newspaper, which asked its readers: “If Kinnock wins today will the last person to leave Britain please turn out the lights”.

The Conservatives were re-elected. “I thought that there was a chance we could lead a minority government,” Kinnock says. “That was the best we could do.”

Deep down, one suspects, Kinnock always felt his chances of becoming prime minister were doomed because of his background and the battles he had to wage to save the party. Yet without Kinnock’s renewal of Labour, there would not be a Blair-Brown “New” Labour government (1997-2010). While he believes they share a commendable record on health, education and human rights, he is disappointed they didn’t articulate it in a conceptually tribal and ideological way.

“Maybe I wouldn’t have been any different, but I think I might,” he says. “They did loads of wonderful things and rarely, if ever, attributed them to the application of democratic socialist convictions. They didn’t say we did this because we are Labour believers, we are taking our hopes and turning them into transformative realities that will help people to live more secure, more fulfilling lives.”

Although a Labour elder statesman, and a life peer, Kinnock seldom intervenes in party affairs. He did, however, call for Corbyn to quit as leader and voted for Lisa Nandy to succeed him. But he expected Starmer to win the recent leadership contest.

Starmer has made a promising start as Labour leader. He has boosted Labour’s support in the polls and is preferred prime minister over Boris Johnson.

But Kinnock says the party needs to overhaul its governing philosophy and policies if it is to regain voter trust. “It requires fundamental, rational thinking and recognising that the world imposes limitations,” he says.

“It is a matter of management, intellectual and ideological rigour, and addressing the manifest needs of the people.”

As Kinnock surveys party he joined at age 14, he worries it has not fully learnt the lessons of its latest defeat. “The whole purpose of being engaged in politics is to secure democratic power to change things,” he says.

“Everything else is peripheral to that central objective. I just hope that Labour won’t take as many beatings in order to learn that as they did last time.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout