Tony Blair’s advice for Anthony Albanese on elections: ‘You win from the centre’

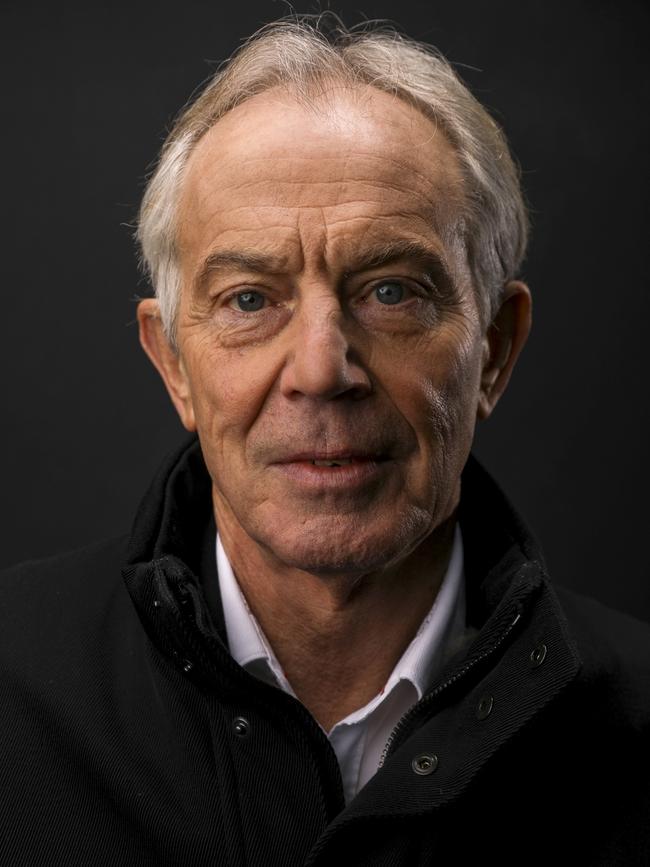

Tony Blair is that rare breed — a prime minister who leaves office at the time of their choosing. And the polarising ex-leader has some advice for Anthony Albanese.

Blair remains a polarising figure in Britain. Although his social and economic achievements as prime minister between 1997 and 2007 are substantial and unmatched since, and he saved the Labour Party and led it to an unprecedented three election victories in a row, many Britons cannot forgive him for the Iraq war.

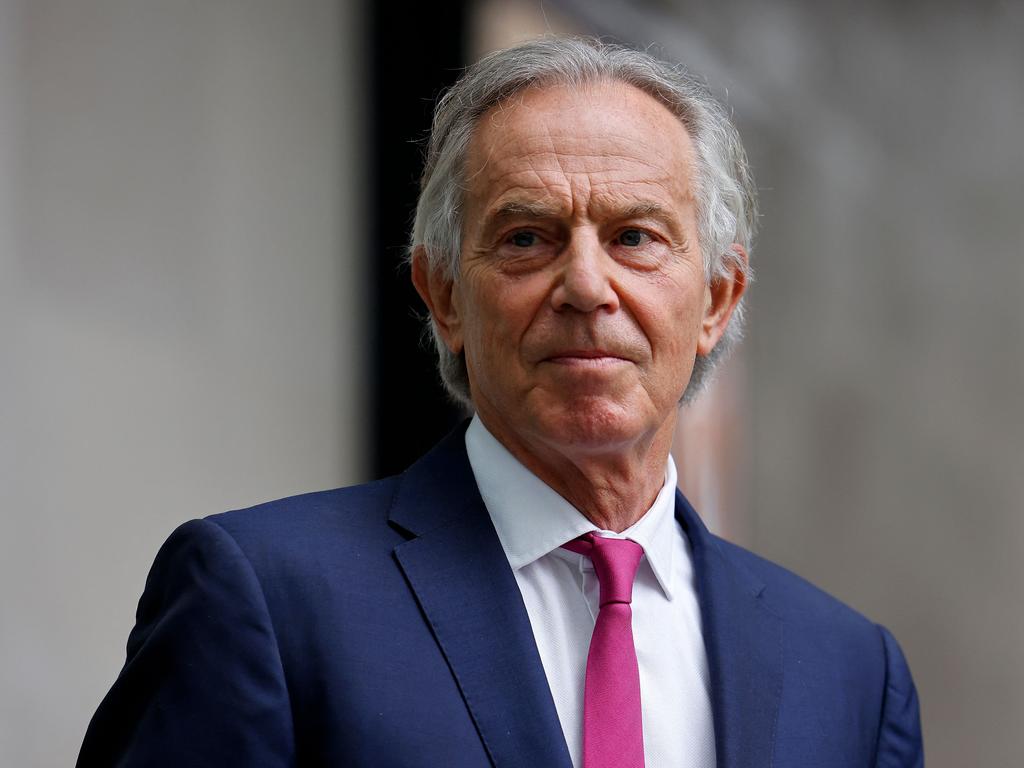

After being checked in by two security staff, escorted into a lift and taken up several floors by an assistant and then met by another staff member, I am ushered in to meet Blair. We have spoken before, when I interviewed him on the phone in 2016, but this is the first time we have met in person.

“Pleased to meet you,” he says, extending his hand and flashing a smile. Blair is relaxed and personable, works his characteristic charm and is casually dressed. He is now Sir Tony but insists we keep it informal. He talks affectionately about Australia and notes his friendship with former West Australian premier Geoff Gallop.

As we talk about contemporary global issues, a post-Brexit Britain, the Labour Party led by Sir Keir Starmer, his decade-long prime ministership and relationship with Australia, I ask Blair why he seems more popular abroad than at home.

“I am regarded as a polarising figure in some respects, but I’ve never been a particularly polarising type of person,” he responds. “I prefer to bring people together. But in politics, when you decide, you divide, and especially if you are there for 10 years. You just accumulate people who disagree with things.” With British politics and media largely bifurcated between left and right, Blair adds that as a centrist he has few natural allies and supporters, unlike Thatcher who garners uncritical praise from the right.

“I am absolutely in the centre,” he says. “With me, because you are not defined in that traditional left or right way, it can be more difficult. But as I always say to people, I won three elections, I didn’t lose them.

“So, you know, there are some people who like you and some people who don’t but, in the end, people were prepared to vote for what we offered. And I think if we kept with New Labour, the whole future of the country would have been different.”

The ex-PMs club has swelled recently to include Liz Truss, Boris Johnson and Theresa May, joining David Cameron, Gordon Brown, Blair and John Major. Blair, however, is the only one to leave 10 Downing Street, essentially, at a time of his own choosing.

In political retirement, Blair has courted controversy for earning huge sums for advising corporations and governments, securing a hefty advance for his memoir, and giving well-paid speeches. He served as Middle East envoy and set up charities and non-profits, with much of his earnings invested in their work.

This post-prime ministerial energy is now channelled through the Tony Blair Institute for Global Change. which employs about 1000 people and works in 40 countries advising governments on long-term strategy, policy design and program delivery, in addition to sharing ideas and analysis for local and international audiences.

“It took time to do what I wanted to do,” Blair says. “It is a massive shock because, for a start, you go from having a huge infrastructure around you (and) we left Downing Street with three people, four mobile phones and no office.

“So, we have had to build this institute. We are now very clear on what we are doing. We are not-for-profit. We focus on helping governments with reform programs (and) I try to use the lessons I learned in government because the toughest thing about government is getting anything done.”

This global engagement means Blair is focused on looking forward, not back, and is in demand to talk to policymakers. He has close links with governments around the world, including the US and Australia, and offers an informed perspective on key challenges and shaping responses to them.

Blair sees the world as divided between two great powers, the US and China, representing the West and East. He regards Australia as spiritually part of the West and says the challenge is not to resist China’s rise but to compete and challenge where necessary while maintaining dialogue and co-operation.

“You have got two huge powers, the US and China, that represent to a degree different interests, but for sure different values,” Blair says. “The potential break-up of the world into these two giant powers, and the countries that associate with them, is the geopolitical challenge of our time.

“The West should be strong enough to deal with whatever comes out of China but stay engaged and stay in dialogue, communication, try and get a means of co-operating where we can as well as obviously competing and confronting where we have to.

“Our problem with China today is around the nature of the regime and what it says and what it represents and what it is desiring to do in the world. Our problem is not with China itself, or the Chinese people, or China being a superpower, because it has got every right to be that by reason of population, strength of economy, technology.”

The key to this balancing act is the West remaining united with strong leadership from the US in concert with Britain, Europe and other democracies in the Asia-Pacific, such as Australia. Blair points to the response from NATO and other countries including Australia in resisting the Russian invasion of Ukraine as a key moment.

“Ukraine has brought us a greater appreciation of the need for Europe and America to work together, to stay together, and has also taught us that things that we thought were unthinkable, you know, you have to contemplate,” Blair says.

The rise of India as “a third giant on the world stage” should also be on the radar for policymakers, Blair adds, as he continues his tour d’horizon of geopolitics and economics. Just what role India will play is still to be determined, as is the nature of its democracy that has reverted under Narendra Modi.

“Modi is providing really strong leadership for India,” Blair says. “It has got a confidence today and a spring in its step that I have not seen before. And, yeah, there will be anxieties – we should note that and watch that.

“But, in part, it is also going to be for the alternatives to Modi to assert themselves in a more, frankly, forward-looking way.”

At a time of global uncertainty, Britain finds itself weaker after exiting the EU. Brexit, even its authors argue, has been an unmitigated disaster. Immigration is higher than it was in 2016, exports have fallen for 16 months in a row, the pound has lost value, tax and spending have increased, businesses face more regulations and consumers face higher prices for goods and services.

Britain has had five prime ministers since the Brexit referendum. Incumbent Prime Minister Rishi Sunak is deeply unpopular and his government is circling the drain. The Conservative Party is in a state of chaos and dysfunction. According to YouGov, Conservatives attract 25 per cent voter support while Labour is at 44 per cent.

Blair says British politics has lost its centre. Labour veered sharply left and made Jeremy Corbyn its leader while the Conservatives conceded to its anti-European right wing and churned through prime ministers. He argues Thatcher would never have taken Britain out of the EU, and instead would have renegotiated its membership. Brexit has bred political instability. “The intellectual force behind Brexit was based on the view that Britain would turn itself into Singapore with deregulation, dropping taxes and opening itself up to the world,” he says.

“The popular vote behind Brexit was almost for the opposite reasons: people wanted to halt globalisation and end immigration.

“What you ended up with, therefore, was a situation in which the coalition that brought us Brexit fundamentally disagrees with itself. And that has been the reason why we have got the problems in Britain.” He adds: “To decide to gamble the destiny of your country in a one-line, one-off, one-day referendum is an extraordinary thing to have done.”

The Blair prime ministership shows signs of being reassessed. He recently marked the 25th anniversary of the Good Friday Agreement that brought peace to Northern Ireland. Blair points to the Civil Partnership Act, which provided legal recognition of same-sex relationships as an important legacy. There was devolution in Scotland and Wales, reform to the House of Lords, and Freedom of Information and Human Rights acts.

While Blair and Brown forged ahead, establishing a national minimum wage, independence for the Bank of England, and reforms to health and education that improved service delivery and citizen choice, their government also took Britain into Afghanistan and then catastrophically into Iraq on the false assumption, albeit backed by intelligence, that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction. “There are things that have been really difficult – post 9/11, Iraq and Afghanistan,” Blair notes. “But, in the end, the most important thing about being a prime minister is ultimately realising it is a lonely job. You are the person who is sitting in the decision-making seat and it is your job to make decisions. Sometimes people agree with you, sometimes they do not.” Blair insists he acted in good faith on Iraq.

Part of the Blair legacy is also the establishment of New Labour, a modernisation project that began with Neil Kinnock, and resulted in a landslide election win with a 179-seat majority in 1997. Blair was, for a time, phenomenally popular and remains a smooth media performer. He is Labour’s longest serving prime minister and the only person alive to lead the party to victory. Starmer, he judges, will also lead Labour to power.

“Starmer, to be fair, has done a great job in pulling the Labour Party back from the madness of the Corbyn years,” Blair says. “He’s pulled it from being on the brink of going out of existence to being on the brink of government.”

The New Labour project and Blair’s third-way centrism was partly inspired by the Hawke-Keating government. Blair visited Australia several times in the 1980s and ’90s, had earlier become university friends with Gallop and Kim Beazley, and lived in Adelaide as a boy in the ’50s.

“I love Australia, the country and the people, and I just wish it wasn’t so far away,” he says, laughing. “Two of the most influential people in my life – Peter Thomson, Geoff Gallop – they made a huge difference to me as a person and in terms of my professional career.”

He met Bill Hayden, Bob Hawke and Paul Keating when they led Labor. He worked with John Howard as prime minister. “With Bob and Paul, we were political soulmates in the centre-left progressive tradition,” Blair recalls. “With John, it was much more security and foreign policy focused. Even though he was from a conservative perspective, I found him a really upright, strong, decent person to deal with.”

A close observer of Australian politics, Blair rates Anthony Albanese and Jim Chalmers highly after their first year in office. Having won re-election twice, Blair advises them to occupy the centre ground, have a clear program for the future and develop practical solutions to policy problems to secure a further term. “Albanese is doing a really good job of giving a sense of direction and momentum,” he says. “It is always tougher for progressive parties to win because they tend to be full of idealistic people who sometimes don’t fully understand electoral realities whereas conservative parties exist to be in power. You win from the centre and you win if you have a clear agenda.”

Blair turned 70 last month, on the same day as the coronation. He jokes that it prompted “anxiety” about his age. Before being elected to parliament in 1983, he had been a barrister and at university played in a band named Ugly Rumours.

So, can he imagine a path not taken into law or rock stardom? He dismisses the first because of an “insufficient sense of purpose” and the second, he says, laughing, because of “reasons of insufficient talent”. If he had not gone into politics, he speculates that he would have done something other than law.

It would be a tougher decision to choose a political career today, Blair concedes, because it is “a brutal business” and the personal toll taken is immense. He describes social media as “a plague on politics” that can ruin lives and also makes it harder to achieve reform.

Viewing politics today as more about an open versus closed mind, rather than the 20th-century notion of left versus right, Blair advises people to consider four things if they are contemplating a parliamentary career.

“Don’t go into it unless it is a vocation and not just a job,” Blair instructs. “Second, have an infinite curiosity about the world. And that means, third, before you go into politics learn about the real world. And the fourth thing is: be true to what you actually believe in.

“Because one of the things I always say to people is that when you calculate too much in politics, you usually miscalculate. I would never have become leader of the Labour Party, or indeed an MP, if you were just advising me from a purely calculating point of view.”

How history would indeed be different.

Tony Blair’s office is located in a nondescript building without signage on a busy London street. When you make it inside, there is no indication that you are in the foyer of the office of the longest serving living British prime minister and the second longest serving after Margaret Thatcher in more than a century.