Baby steps on way to nation’s make-or-break challenges

Paul Keating demands policy audacity but Anthony Albanese is comfortable flying low.

The new Labour Prime Minister has five key missions, one of which is making Britain a “clean energy superpower”. Another is breaking down barriers to opportunity. Sound familiar?

In rebuilding Britain, should Starmer go big via “mission-driven” government, in the manner of the left’s divine wonkette Mariana Mazzucato, and risk reducing the ailing place to rubble?

Or move softly-softly, in small but quick steps, racking up policy wins that add up to something substantial across time? That latter approach, described as “radical incrementalism”, is being pushed by Torsten Bell, one of Britain’s most influential and creative economists, who was elected three weeks ago as Labour member for Swansea West in Wales. Before standing for parliament, Bell was the head of the Resolution Foundation.

The left-leaning not-for-profit think tank, with a focus on improving the lives of people on low to middle incomes, was instrumental in designing the Coronavirus Job Retention Scheme (the UK’s version of JobKeeper).

Bell’s Great Britain? How We Get Our Future Back was published last month and has generated a keen interest in policy circles, including among leading figures in Canberra. Bell argues for a “new patriotism” based on reviving productivity growth and investment. Not a nostalgic return to manufacturing, as Mazzucato and her acolytes contend, but revival through services where the nation is on the global frontier of innovation and exports.

“This approach is genuinely patriotic: it does not ignore the real problems the country faces, but is confident that a better version of Britain, not an imaginary one, is desirable and achievable,” Bell writes. “Its method is one of radical incrementalism – radical to reflect how far the status quo is failing us, and incremental because lasting change is achieved by improving reality as we find it, not by wishful thinking.”

On sensible fiscal grounds, Bell argues against the leftist folly of a universal basic income, or a cheque for everyone, to end poverty and reduce inequality. The country simply can’t afford a UBI that would make a difference.

Bell also wants to shift the burden of tax away from income and to wealth; in this, he’s not far away from the view of some of our most esteemed retired officials, though none of them has ever stood between a boomer and cheeky capital gain.

While the specific measures Bell advances are intended for Britain, with its council taxes, national insurance and pay-setting laws, the implementation strategy of the reform program is what catches the local eye. “Over time, a lot of sensible, small changes, with bipartisan support, can make a huge difference, especially in the key spending areas of the budget,”says a senior official citing the Bell schema.

Anthony Albanese may no longer yearn to fight Tories, but he is certainly of the gradualist mindset. The Prime Minister won in 2022 on a modest platform, mainly not to be the “other guy”; Scott Morrison was the least popular main party leader in the 35-year history of the Australian Election Study. The Labor leader campaigned in sharp contrast to his predecessor Bill Shorten, whose 2019 platform of social redistribution was as poorly understood as he was personally rated.

Enter Jim Chalmers, the disrupter of capitalism, at least in Essayville. The custodian has proven to be a patient agent of change, resigned to operating at Albo speed at a time when high inflation and slow growth have eaten up political capital and executive appetite for risk.

Amid the early grind of post-Covid fiscal repair, Chalmers explained to Guardian Australia the essence of Labor’s homegrown incrementalism. “My theory of governing is people will cop big things done slowly and little things done quickly, but not big things done quickly or little things done slowly,” the Treasurer said.

Paul Keating was a “big things done quickly” reformer, but someone who kept educating voters about the cascade of policy shocks. In Bob Hawke he had a partner who expertly managed the vested interests. Keating laments the nation’s chronic timidity in vision and action. “In public policy and leadership, there is a permanent case for audacity – a permanent case,” he recently told Troy Bramston.

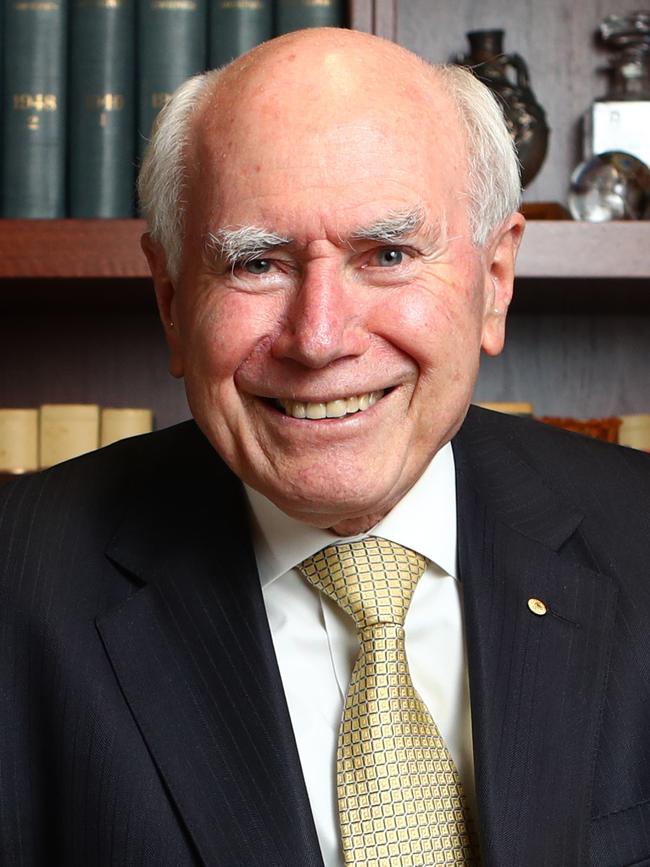

Perhaps the two standout instances of policy bravado of the past two decades were John Howard’s Work Choices and Julia Gillard’s emissions trading scheme. Big and bold, but buried immediately by their political opponents.

It’s plain to see why officials like gradualism. You get stuff done. It’s a simpler life than, say, turning the tax system on its head as the retired four-star generals of the fiscal industrial complex are wont to recommend.

Sure, let’s aim for the stars, such as 1.2 million new homes. But, a bureaucrat might say, if you put carrots in front of local councils, maybe the zoning laws become more friendly to medium-density dwellings in areas where young people actually want to live and work. It’s a steady win-win, but the photo-ops may be few and far between for Canberra’s Alphas.

Another argument for incrementalism is that “the system” ain’t broke. That may be a harder argument to mount in battered Britain, which Bell refers to as “stagnation nation”. In a recent speech, Reserve Bank deputy governor Andrew Hauser, an Englishman, spoke about his new home’s diverse natural gifts, above and below ground, and beyond the sea.

“Endowments bring opportunity,” he went on. “But harnessing them for a country’s greater good takes something more – and Australia’s real secret sauce has been its strong but adaptable pro-growth institutions.”

Across its history, the country has also welcomed foreign investment. Put those things together and Australia has been able to navigate the massive changes in the global economic and financial order – and win.

“No one has yet identified a single golden source of national prosperity,” Hauser said. “But Australia has come pretty close.”

Enormous national pay rises from the rest of the world, through record export earnings and cheaper imports, have helped. All up, we managed the pandemic better than most, although the fiscal legacy is a structural gearing to deficits and homegrown inflation.

Voters say they want governments to do big things – net zero, fast rail, affordable housing and healthcare, compassionate aged care and disability services, on-budget nuclear-powered submarines and baseload power, and social cohesion – but are wary of being worse off in the execution. They dream like Keating but want the comfort slippers of Howard

Albanese’s Future Made in Australia probably isn’t ambitious enough to qualify as big. Joe Biden’s industrial, chip-making and green energy superstructure leaves every other would-be interventionist in the shade.

But FMIA does manage to tick the “risky” box, as the Productivity Commission reminded us this week in its annual industry assistance stocktake. Treasury’s guardrails for investment may work, but only up to a point. We need off ramps so taxpayers aren’t on the hook for bureaucrats’ mistakes on dud projects. As well, numerous alternative funding vehicles remain for off-road – that is, off budget – adventures.

Elsewhere, gradualism is the dominant mode. Labor is pushing ahead on competition policy, including merger reform, and has tightened up parts of taxing multinationals and superannuants. After Labor’s 2019 episode Chalmers, or anyone else for that matter, is unlikely to end the tax breaks for negative gearing and capital gains, or go anywhere near changing the treatment of the family home in the pension assets test or an inheritance tax.

Canberra has a fragile compact with the states on containing the National Disability Insurance Scheme, a fiscal juggernaut. Reforms to aged care, including injecting a few price signals into services, appear stalled. A “10-year rebuild” of the migration system may be the poster child of Labor’s incrementalism, as it works through a list of reform directions to up-end a status quo that was failing the nation and those who wish to settle here.

Compared with the Coalition’s radical alternatives that grab a few days’ worth of headlines – uncosted nukes, a handbrake on skilled migrants and corporate divestiture – gradualism looks the safer bet. Anyone thinking of Making Australia Great Again, however, will require the back-to-back-to-back tenures the Coalition indulgently burned and the Tories just squandered.

For plodding Albanese Labor, once so fresh and steady, successive terms in its own right may turn out to be a radical hope as well.

Amid stagnant British living standards, failing social services, rickety infrastructure and plummeting levels of trust in a decrepit Conservative government, Keir Starmer’s election victory was as inevitable as it was emphatic.