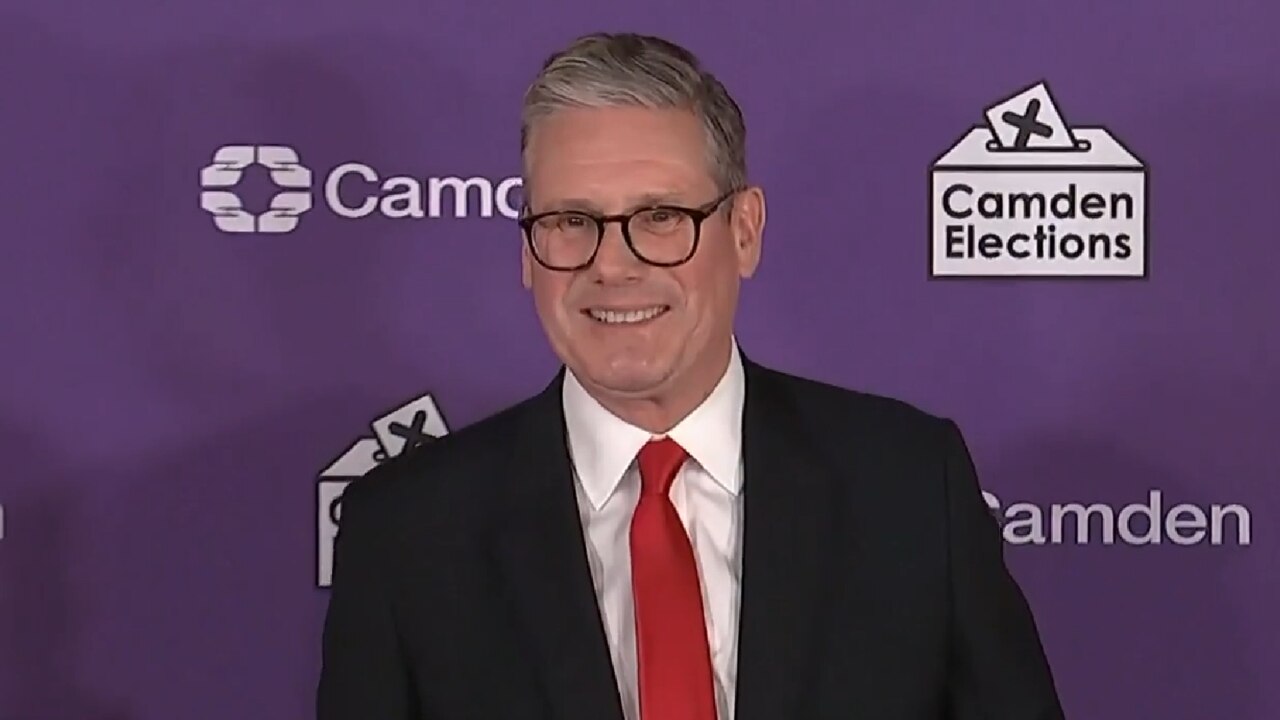

Self-described socialist Starmer is set to drag country to the left

While Europe swings to the right, the UK is heading in the opposite direction. But Keir Starmer and Labour are not popular.

Labour will have a huge majority in the House of Commons.

Nigel Farage, challenging the Conservatives on the right, has taken a swathe of votes, and gravely damaged the Conservatives, but won only a handful of seats.

It was this fracturing of the centre-right vote in Britain’s first-past-the-post electoral system that has made the result so devastating and one-sided.

But the outcome itself is full of paradox. Though the British public were absolutely fed up with the Conservatives, fed up with their internal hatreds and feuds, the messy way they implemented Brexit, the long run of scandals, persistent high immigration and, the chief killer, the deadly rise in the cost of living, nonetheless the election turnout was sharply down on five years ago and miles below the turnout for the 2016 Brexit referendum.

Starmer and Labour, despite their massive win, are not popular according to opinion polls. This was a vote no, not a vote yes.

Incumbent governments, still wrestling post-Covid inflation, have been falling all over the Western world. Western electorates are in a cynical, frustrated mood.

Starmer has pulled Labour back from the wild extreme of leftism it embraced under surely its weirdest ever leader, Jeremy Corbyn. But despite his reassuring tone during the campaign, Starmer will take Britain a long way left. Starmer describes himself as a socialist and a progressive. He happily served as a key figure on Corbyn’s front bench. He was a far left activist as an undergraduate.

As with many lawyers on the left, he will favour tying Britain in an ever more complex web of international and specifically European treaties that will tend to override British domestic law.

Starmer was always seen as soft left, compared with Corbyn’s hard left. But the Labor Party itself has moved much further to the left. Its big Muslim component has little respect for Starmer, whom it accuses of being too friendly to Israel and not hard enough in support of Palestine.

Starmer’s Labour is committed to early recognition of a Palestinian state. It is committed to NATO, to continuing to support Ukraine, to being reliable on defence and indeed to honouring AUKUS.

However, Britain has no money to spare to embark on Labour’s vast social policy ambitions. Starmer has promised much greater availability of medical services, the public sector unions are all demanding big pay rises, he’s promised infrastructure development and a huge house-building program.

Very soon, Starmer will find, like governments have found all over the Western world, that an ageing and ailing society wants a lot more social spending, that this is beyond even the money brought in by today’s record taxation levels, that defence is increasingly expensive and party activists, on left and right, are increasingly unwilling to compromise on their demands.

Historically, British Labour has harboured deep divisions over Britain’s nuclear missile submarines, as well as its conventionally armed nuclear attack submarines, the type Australia wants to acquire.

Its submarine program is stretched, behind schedule, low on human resources and chronically challenged technically. The financial pressures on the program, plus the drift of Labour politics, may well imperil the AUKUS subs in the medium term.

The Conservatives have mostly fended off Farage’s party. The Conservatives remain the biggest party in Opposition, the only party that can offer a medium-term alternative to Labour. The earth shook, but the building stayed upright.

Still, the campaign was notable for all the big issues that were not discussed. The best line of an extraordinarily dull and low-quality British general election campaign came, unsurprisingly, from former leader Boris Johnson.

At the last minute, Conservative Prime Minister Rishi Sunak drafted Johnson in to reinforce the Conservatives’ Dunkirk save-the-furniture strategy by emphasising to the electorate the downside of handing Labour’s Sir Keir Starmer a massive landslide majority in the House of Commons.

The worst enemy of the Conservatives had turned out to be Nigel Farage’s Reform Party, which was taking votes directly from the Conservatives and making it much harder for them to hold on to what were previously safe seats.

But Farage made a stupid mistake.

Echoing lines that work to a certain point in America but not Britain, he blamed the Western alliance for Russia’s war on Ukraine.

“We provoked Russia,” Farage fatuously declared, the kind of thing the former leader, Corbyn, might have said.

Thus Johnson declaimed: “Don’t let the Putinistas deliver the Corbynistas.”

Johnson also warned that Labour would “whack up taxes” and “persecute private enterprise, education and healthcare”.

He said the Conservatives had at last “defeated Covid and defeated post-Covid inflation”.

Johnson was coherent, cut through, sharpened the difference with Labour, and passionately believed what he was saying.

That Johnson’s was the most memorable intervention by a politician says a lot about how unspeakably dull the other leaders have been.

Sky News’s Beth Rigby asked Starmer about his own dismal personal approval ratings. Labour was miles ahead, yet Starmer had the lowest approval ratings of any opposition leader about to win.

Would Starmer, she asked, have the biggest wedding ever, and the shortest honeymoon?

Starmer replied with the sort of non-committal, bureaucratic blather of which he is master.

I have previously written that Starmer resembles a British Anthony Albanese. He came from a working class background, did well at university where he was a far-left activist. Unlike most politicians, he had a big career before politics, as a human rights lawyer, then Director of Public Prosecutions.

Starmer is brainy and works hard. Too deep immersion in the law has rendered it impossible for Starmer to write felicitous prose or create memorable images. Perhaps he’s a British combination of Albanese and Mark Dreyfus, with a touch of Gareth Evans.

Starmer has provided a small target. It’s not clear people are voting primarily for Labour; they voted ferociously against the Conservatives. Starmer tried not to interrupt while the Conservatives committed political suicide.

Former home secretary Suella Braverman encapsulated the dismal Tory performance: “We failed to cut immigration or tax, or to deal with the net zero and woke policies we have presided over for 14 years.”

Starmer was less precise than Braverman in his criticisms. He used the routine abstract nouns to describe the government – chaos, disunity, confusion, dishonesty, division and so on. But he wasn’t too specific about key policies. If he beat the Tories for failing to cut immigration, that might lead to Labour having to offer its own specific immigration target.

Starmer made some promises, mostly over a long time frame. He’s committed to building 1.5 million new homes in five years, similar to Albanese’s target of 1.2 million new homes in Australia, also over five years. In fact, there is an eerie similarity between many of the issues in the UK and in Australia.

The Albanese government won’t achieve its house-building target, and the Starmer government is unlikely to achieve its target, just as the Jacinda Ardern Labor government failed dismally to achieve its house-building target in New Zealand.

The reasons are complex and structural and go to the heart of the inability of Western societies to resolve policy disputes and achieve concrete outcomes. Building houses seems straightforward. But Western democracies now have super effective blocking mechanisms. Far from being dictatorial, very often the centre can’t achieve anything much at all.

In all Western societies, housing involves a complex, overlapping set of authorities and differing levels of government. Left-of-centre governments have enormous difficulties because their socialist, or even just social justice, instincts conflict with their green instincts. The green movement is essentially a movement of middle class privilege. There is a huge streak of NIMBYISM in all green politics. No one who lives in a house near a green field wants the field given over to houses. No one in an area of individual houses on individual plots of land wants these exchanged for apartments.

The Conservatives were hopeless at transcending contradictions like this. Starmer will find them difficult too. The same on immigration. Starmer says he wants to bring immigration down. The Conservatives have never recovered from net immigration reaching more than 700,000, a record, in 2022. This showed up the hopeless ineffectiveness of the Conservatives on core policy issues. A huge impetus for the Brexit vote in 2016 was the desire to regain sovereign control of the nation’s immigration program. They never implemented the tough-minded policies that would be necessary to make that happen, although they can claim they were stymied quite often by an obstructionist House of Lords.

Starmer mocked Sunak’s Rwanda plan, which was modelled on Australia’s border control policies. Under this, which the courts and the House of Lords between them prevented Sunak from implementing, asylum-seekers who arrive in Britain by boat would be taken to Rwanda and their claims evaluated there.

But when asked in interviews what he would do about illegal immigrants arriving in record numbers, Starmer would only say that he’d negotiate to send them back to Europe or back to their country of origin. This would be very difficult. However, he would begin onshore processing of illegal boat arrivals again. But Britain, like most Western nations, has been absolutely ineffective in repatriating failed asylum-seekers. Starmer will face the further contradiction that many in his party are against tough border controls. It’s hard to imagine that a Starmer government will establish effective control of Britain’s borders.

Starmer says he’ll be strong on security and defence, but that cuts against much of his party. And he may soon have to deal with Donald Trump in the White House, which his whole party will hate. Yet Britain, like Australia, profoundly values the US alliance.

Starmer will start his term with immense authority, but voters these days are cantankerous, demanding, unforgiving and not very deferential to any political authority. Like Albanese during the last federal election, Starmer has tried to sound conservative. He told The Times his top priority would be wealth creation.

That is a worthy ambition. Britain is an ageing and ailing society, with low productivity, and low productivity growth. It desperately needs a burst of supply-side economic reform that turbocharges growth, combined with intelligent but ruthless fiscal discipline.

There’s nothing in the modern Labour Party to suggest that Starmer can deliver that.

The Conservatives got into so much trouble with their base partly because they could never work out whether they were a low-tax, free-market party, a la Thatcher, or a big-spend, big-tax, big-government right-of-centre party, like many US Republicans and much of the populist right in Europe.

France is a good example. In its recent election, both the triumphant right National Rally of Marine Le Pen, which came first, and the far-left coalition, which came second, were determined to reverse Emmanuel Macron’s mild, necessary pension reform which raised the retirement age from 62 to 64. This determination to restore unaffordable social spending reflects the insight of Henry Kissinger that Western governments are now completely incapable of asking any short-term financial sacrifice from their electorates in order to secure long-term benefit.

Starmer endorsed the Conservative commitment to leave personal income tax brackets untouched until 2028. This means through bracket creep there is a substantial real rise in taxation. Yet tax and government spending are already at a record high since the unique period just after the end of World War II.

For all that, Starmer deserves credit for winning a historic victory.

The Conservatives, though any government would be in trouble after 14 years, deserve all the criticism they are getting for making such a mess of the past few years in particular.

After the long Tony Blair/Gordon Brown years of Labour hegemony, the Conservatives finally came back to office in 2010 under David Cameron. But it was a very equivocal victory. Cameron didn’t secure a majority and had to govern in coalition with the Liberal Democrats.

He styled himself “Blair’s heir” and his version of modernising the Conservative Party was to go left on cultural issues and green policy, especially all things related to climate change, and to pursue fiscal discipline through austerity.

Green policies were cheaper in those days because it was before the industrial societies realised that to meet their climate targets they would need effectively to deindustrialise and embrace vastly more expensive renewable energy schemes.

Cameron’s move left culturally and on green issues fed into the rise of Nigel Farage and the UK Independence Party. UKIP got millions of votes in both European elections and British national elections. In response, Cameron went to the 2015 election promising a referendum on Britain’s membership of the EU. Surprisingly, he won a parliamentary majority.

Then in 2016, mainly because of Johnson’s advocacy, and against Cameron’s desperate campaigning, Britain voted to leave the EU. The bien pensants around the world now claim Brexit was a terrible mistake. In fact the Tories have made a mess of running Britain since Brexit but Brexit itself was a very good move.

France’s economy is mediocre and the nation is riven by social conflict. Germany is in recession. Neither undertook Brexit. But now, with Brexit completed, the Tories are rightly suffering from their failure to reduce immigration as they promised. They can no longer blame the EU. Responsibility, and power, rest where they should, with Britain’s government.

After a dithering and ineffective prime ministerial period under Theresa May, Johnson claimed his rightful place as leader and won a smashing victory in 2019, with a majority of 80 seats for a nine-year old government seeking its fourth term.

Like all Western governments, Johnson’s was nearly destroyed by Covid. Its actual performance wasn’t too bad, with a fast vaccine rollout. But Johnson’s chronic lack of personal discipline led to the greatest political tragedy in modern Britain. All of Johnson’s once-in-a-lifetime political talent was washed up in the scandal arising from him and his staff attending parties, against the strict Covid rules imposed on everyone else. Johnson lost the leadership to the briefest reign by Liz Truss, replaced in her turn by Sunak.

Sunak, a good man, was the best technocrat in the Conservative Party and all governments need some technocrats. But he wasn’t a gifted communicator or leader. Also, by the time he became leader the Tories were a poisonous brew of entrenched, visceral personal hostilities, vendettas, blood feuds and tribal warfare.

The challenge for the Conservatives now is not to move either left or right but to form an effective opposition, not surrender on key cultural issues, hold the new government to account, and keep the party together, much as Peter Dutton has done for the centre right in Australia. Compared to Starmer’s task, it’s small beer. But for Britain’s sake, and the world’s, both sides of British politics need to calm down and get serious.

Just as Europe swings to the right, Britain swings decisively to the left. For once the polls were right, Sir Keir Starmer’s Labour Party won a huge victory in the British election. Rishi Sunak’s Conservatives have been crushed, recording their weakest result in this century or the last.