Will Jim Chalmers become the change agent Australia needs?

As fiscal pressures build, the tax system is failing on all fronts. Will Jim Chalmers become the change agent Australia needs?

The 46-year-old has conceded his tax work has been “modest but meaningful” – and that was before Labor redesigned the stage three tax cuts, the original a piece of simple fiscal housekeeping with aspirational hues via a $20bn annual tax flattening.

On Thursday, at the SCG of all places, Chalmers began laying the rhetorical groundwork for the May 14 budget, skiting that Labor’s assorted super tax grabs and technical tweaks amount to “probably the biggest agenda certainly for 15 years, maybe 25 years.”

The fiscal pressure is building – as the post-pandemic revenue bonanza subsides – and the country needs a more robust tax base. A likely second successive surplus this year due to a temporary burst of revenue can’t hide the budget’s structural weaknesses, on both sides of the ledger. Forever spending is growing because of ageing and, let’s not kid ourselves, because Australians want it all.

According to those who know it best, our tax system is defective in fundamental ways. On the standard criteria – revenue adequacy, economic efficiency, fairness, risk and complexity – former Treasury secretary Ken Henry argues, “Australia’s tax system fails on all legs.”

Just after Labor took office, Treasury secretary Steven Kennedy said it was within the nation’s control to maintain improved standards in aged care and disability “while reducing pressures arising from poorly designed policies”. Let’s see how Labor goes on two big-ticket items that can’t sit much longer in ministerial in-trays.

“We will need a tax system fit for purpose to pay for these services, that appropriately balances fairness and efficiency,” Kennedy told business economists in June 2022. “This is achievable.”

That optimism for managing change goes against history and the current run of play, where cost of living dominates our political economy and the budget, when you take out the rainbows, is running at a $25bn a year deficit.

Peter Costello, the last custodian to land systemic tax reforms, claimed tax was the hardest reform of all.

Returning bracket creep, which never sleeps in a system where nominal wages rise and the thresholds aren’t indexed, is not tax reform; all governments make a song and dance about kicking back from time to time years of accumulated fiscal stealth that sees average tax rates rising.

Even after the rejigged tax cuts kick in on July 1, the Parliamentary Budget Office has projected the average tax slug for individuals will steadily rise and hit a record high of 27 per cent in 10 years.

In a new book, Mixed Fortunes: A History of Tax Reform in Australia (Melbourne University Press), Paul Tilley details the hazards and pinpoints the reasons behind the three episodes of successful reform – income tax unification in 1942, Paul Keating’s 1985 reforms and Costello’s 2000 new tax system that introduced the GST.

Tilley explains that reform is elusive but the benefits can be large, especially for growth in productivity and living standards, and which is central to perceptions in the land of the fair go. “The tax system is like a social contract between the government and the people,” he tells Inquirer.

“Citizens give the state the right to raise tax to fund public services. But the system also has to be fair. In the midst of the current politics around cost of living, there are pressures on this so-called taxpayer morality and we don’t want it to fray like it did in the 1980s when there was widespread avoidance and evasion.”

The former economic policy adviser, who has published a history of the federal Treasury, mixes scholarship with life lessons from the grind of advising governments for 30 years. He says it requires a rare alignment of the stars to get meaningful change, especially the right political economy setting.

In horse racing terms – and this is me, not Tilley – you need a “quaddie”, or quadrella; that is, four winners in a row: sound policy arguments, the right change process, strong political leadership and good timing.

Governments often opt for a wide-ranging formal review. Before they can act, they need to establish there is a problem that needs to be addressed. A review – internal, external or some combination between – can canvas options that may be too controversial for the government of the day.

Within this, Tilley explains that reviews can be foundational (establishing the initial case for tax reform) or determinative (where governments are ready to roll and it’s mainly about implementation).

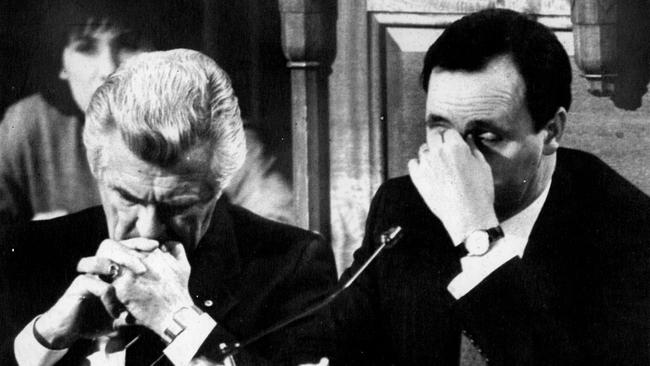

Getting the politics right requires storytelling, courage and a strong budget position, which governments led by Bob Hawke in 1985 and John Howard in 2000 did so well. Even so, those two successes were mixed, as University of Melbourne tax expert Miranda Stewart notes in the book’s foreword. In 1985 it was Option A that was enacted, not – as Stewart reminds us – “the optimal tax approach” of Treasury’s cherished Option C with its broadbased consumption tax.

Howard’s GST, too, was sub-optimal, with its relatively narrow base because of exemptions and a host of nuisance state taxes still on the books. It has not proven to be the growth tax that was promised, and in a decade still will raise the equivalent of only 3.5 per cent of GDP, where it is today.

Stewart, a visiting fellow in Treasury’s revenue group, says the Henry review (2009) had the vision and breadth to be the platform for future reform but was derailed by the global financial crisis.

She also notes the “demoralising experience” of the enactment and repeal of two taxes that could have made a significant difference to the sustainability and effectiveness of the tax system, namely the carbon tax (or Julia Gillard’s emissions trading scheme) and the resource super profits tax.

“We are still grappling with the legacy of those tax reform failures,” Stewart writes.

Tilley says the Henry review is an invaluable foundation, with a steady stream of its 138 recommendations eventually finding their way into the world as law, in defiance of the partisan critiques that said only 1½ of its measures saw the light of day.

International bodies have been constant in their push for tax reform. In its health check on Australia, published in January, the International Monetary Fund called for “a more growth-friendly tax structure” and saw “merit in a comprehensive tax reform”, by rebalancing the system from direct to indirect taxes.

The IMF said high reliance on personal and company income tax was amplifying the challenges of financing future health and aged care, while noting the growing dependence on bracket creep. “Addressing these challenges head-on will avoid costly delays in tax reforms needed for sustained and shared prosperity,” it said.

Tilley and others have identified other areas for reform, including inconsistent taxing of savings, road user charges, land tax to replace stamp duties, better taxing of profits in a global economy and getting a superior deal for taxpayers for the sale of resources, with offshore oil and gas at the top of the list, despite Labor’s fiddling.

As Tilley shows, in any change to the tax burden, short-term winners and losers are apparent. But it may take years for the benefits of improved efficiency, equity and simplicity to be realised. Hawke and Howard were prepared to burn political capital for the national interest and were blessed with skilful treasurers to manage the big-picture narrative and bureaucratic nitty-gritty.

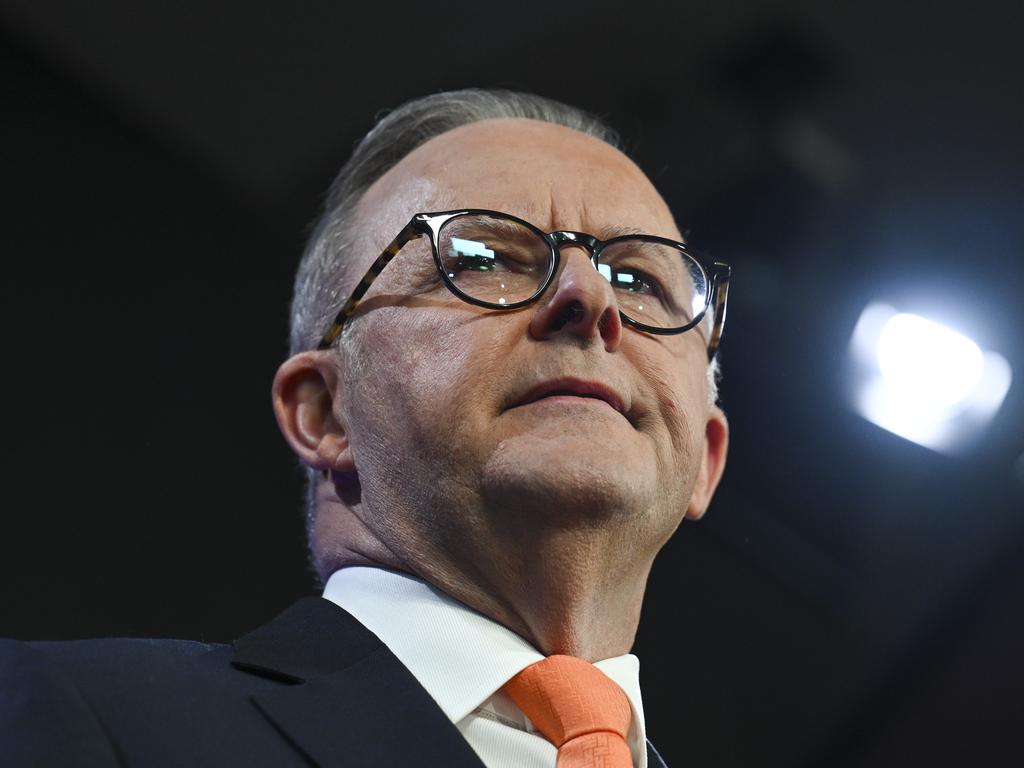

The emerging view inside Canberra’s political and policy engine rooms is Chalmers has the ambition and ability to be a change agent, or a “searcher” as one economist calls democratic politicians; our elected representatives are, all things considered, better policy innovators than experts, bureaucrats and keyboard know-it-alls.

Yet the Treasurer tinkers, tailors his message, soldiers on and espies only low-risk targets such as multinationals.

Tilley’s ride through history is dispiriting because of the odds against a big bang on tax. Yet he remains hopeful: if you build the case, the moment will come. “A reformist government needs to be ready to move quickly when the political window for reform is flung open, such as early in a new government’s term or even in a crisis,” he writes.

The former Canberra official tells Inquirer governments need to establish there is a “burning platform”, a problem that must be solved, before they can truly spring into action.

This week, Business Council of Australia president Geoff Culbert warned the nation was losing ground, amid falling student performance, dire productivity slippage and capital flight.

“We are going backwards on so many critical measures,” he told a business summit dinner. “We have a burning platform and unless we do something about it, it will only get worse.”

Culbert argued we were in a “jail of short-term thinking”. To get proper tax reform, we need to take political risk out of the equation, rely on experts, invite people into the conversation and build the case for long-term changes.

That sounds as sensible as it is naive; it goes against every instinct of the current political class, including tribal warriors Anthony Albanese and Peter Dutton. Consensus leading to reform will require an even greater exotic outcome than a four-strike quaddie, something like an act of God.

After almost two years at the crease, and a third budget two months away, Jim Chalmers has made a tentative start on reform. No wild swings or playing and missing, but signs of intent. Not sure, however, about a creeping tendency to hog the strike. In his comms-heavy, congenial manner, the Treasurer is like his budget brother Josh Frydenberg – playing the long game, thinking time is on his side, building relationships across the economy’s institutions.