Prime Minister is failing to seize the moment

The nation and its leaders reek of complacency. Wake up, Australia, it’s time to tool up, tune in and get to work.

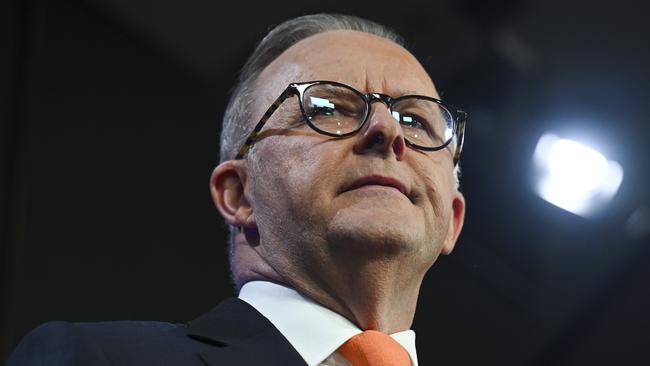

Amid the summer hiatus, Anthony Albanese has been hyperactive on the messaging front, trying to reconnect with voters.

Season ’23 fizzled out after a thumping rebuke for the Prime Minister at the October referendum to establish an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander voice.

On Thursday, he vaulted into the political year at the National Press Club, a day after dumping the legislated stage three tax cuts and rallying his MPs in Canberra.

Albanese insists circumstances have changed, but the policy song remains the same; the triumph of short-term politics, a hope that the rush never ends.

Canberra’s political class is stuck in a rut. Labor is gun-shy on reform and Peter Dutton’s gang are rarely out of their post-election bunkers.

All this sound bite and partisan fury, signifying stuff all. But the Albanese government owns the go-slow, courtesy of its May 2022 victory on an ultra-low primary vote and low-calorie platform.

OK, it honoured social policy commitments, from childcare to aged care, and legislated more ambitious emissions targets. Labor is desperately trying to prevent the National Disability Insurance Scheme from imploding, but is at the mercy of mendicant state partners to save it.

The migration strategy is sound but a lack of urgency in implementing the new road map, as in other areas, reveals timidity at the heart of government. Its operating mode looks exactly like the previous tenants’ mantra: it’s the politics, stupid

The Prime Minister scoffed this week about do-nothingness, declaring more than once he was in this game to make a “real difference to people’s lives” not just occupy the executive suite and official residences.

But the country is in a torpor, reflecting anaemic growth beholden to a record inflow of half a million migrants. Economists are calling it a “per capita recession”.

We’re muddling through because of bumper ore, coal and gas prices, the federal budget boosted by the supercycle, jobs bonanza and fiscal larceny the original stage three tax cuts would have partly addressed.

A former senior diplomat, with contacts across the globe, tells Inquirer the nation’s ruling class, for want of a better term, is listless and disengaged. Business Council chief executive Bran Black concurs about the lack of urgency in Canberra. It’s not that Labor is anti-business, per se, although look at the wharves and re-engineering of workplace laws – they don’t scream flexibility, innovation and high performance.

“I think the greatest challenge that we face right now, from an economic perspective, is complacency,” Black told Sky News this week. That was before Albanese ditched the stage three tax cuts and opted for slicing the pie in a new way.

Before Christmas, Treasury was asked to come up with an option to ease the squeeze on Middle Australia – and revive Labor’s political fortunes – without igniting inflation; officials were not the prime movers on the tax changes.

The advice on amending the tax cuts released on Thursday flatly rejected the calls to “spend” the forgone revenue from stage three, estimated to now be $19bn in the first year, on other social programs. “It remains important to deliver an overall tax cut around the size of the stage three tax cuts to unwind bracket creep and lower average income tax rates,” Treasury said.

“This case is supported by the ongoing improvement in the budget position and adverse impacts of rising average income tax rates. Maintaining the overall magnitude of the cut (and thus the broad budget impact of stage three) also ensures that any redesign does not add to inflationary pressures.”

Treasury then notes that “ensuring average tax rates for high-income earners do not rise too high and that the top marginal tax rate is only paid by a small share of taxpayers also remain relevant objectives.”

Labor’s fix amounts to housekeeping before a storm hits the roof. Indexation of the tax brackets, as occurs in many countries and imposes discipline on the spenders, is probably a pipe dream.

But the tax system needs an overhaul, as global agencies such as the OECD and International Monetary Fund have been telling us for years. Reform is a gateway to efficiency, intergenerational fairness and, ultimately, higher productivity growth and living standards.

A week ago, the IMF published its annual health check on Australia. We have solid public finances (if you hide sub-par Victoria at the back of the room), a robust banking system, and essentially “full employment”. We are cutting emissions (albeit in a very costly way) and building transport and energy infrastructure (ditto on cost blowouts). The IMF gave Albanese the green light in its initial report late last year to scale back spending to support state public works, which were poorly co-ordinated and managed; the mega-project boom was beyond the industry’s capacity, requiring the Reserve Bank to raise interest rates higher to fight inflation.

If you’ve wandered past a rail, road or tunnel construction site in our capitals over the past few months, you’ll have seen your tax dollars at work – but not the penalty-rate princes and princesses, sitting in utes with the engine running, eyes down on their phones, enjoying the blast from the aircon. That’s a pervasive symptom of decay, poor governance, and a failure by all players to serve the public.

In its final report, known as an article IV, the IMF again highlighted the need for tax reform, with a bit of uncharacteristic bureaucratic frustration thrown into the pot. Tighter budgets would aid in the fight against inflation. “A more growth-friendly tax structure and measures to improve spending efficiency would help address supply-side constraints,” the IMF said.

The Washington-based body saw “merit in a comprehensive tax reform and highlighted that rebalancing the tax system from direct to indirect taxes”. Australia is right at the top of the global ladder in reliance on direct taxes, such as personal income and company tax, which account for more than 60 per cent of revenue. Other advanced economies with an AAA credit rating, such as South Korea and Canada, make do with a 40 per cent share, and put greater weight on taxing consumption.

The IMF said tax reforms remain “indispensable to long-term fiscal sustainability and productivity”.

“High reliance on direct taxation is amplifying challenges of financing health and aged care as population ageing lowers the share of workers, and declining productivity growth puts a drag on wages,” it said.

“The 2023 Intergenerational Report underscores the growing dependence on bracket creep in the absence of tax reforms. Addressing these challenges head-on will avoid costly delays in tax reforms needed for sustained and shared prosperity.”

While noting the work to reduce emissions (although “a broadbased economy-wide carbon price is still not being considered”, it snips), the IMF, won’t be holding its breath on tax reform.

“The longstanding policy advice of rebalancing the tax structure away from direct taxes to indirect taxes remains difficult to implement,” it concludes, reflecting the sentiment at Treasury.

The IMF’s evidence on our performance against peers, trade partners and competitors delivers a reality check. Again, it’s not the look-at-me stats on jobs and falling inflation, but the ones that reveal our vitality, initiative and ability to adapt.

One of Labor’s touchstones is a “future made in Australia”. Well, we are treading water as a manufacturing nation. Between 2012 and 2022, we had no growth in manufacturing productivity, as measured by so-called “growth of real manufacturing gross value-added per hour worked”. Zero.

Over the decade, the UK had annualised growth of 2.3 per cent on that measure, while 19 countries in the Euro area achieved 1.9 per cent a year. And we want to build nuclear subs!

We live well, especially when the world confers a pay rise via record export prices. But we’re a high-cost destination to visit, run a business, or buy a home. The average growth in our unit labour costs over the two decades to 2021 was 4.1 per cent a year; in the US, it was 1.6 per cent, and 2.8 per cent in Germany. Wow, we must be doing something right, right?

We’re pricing ourselves out of the market in many activities. Not just against the low-cost factories to the world in Asia, but in a range of services as well. This will come back to bite us, as will our poor record on investing in R&D, where we spend an average of just under 2 per cent of GDP, equal to Norway and just above Canada.

But countries on the global frontier of innovation – such as the US, Germany and Japan – are spending 50 per cent more as a share of their economies.

In the end, the IMF says Australia remains resilient in the near term “but confronts a secular productivity slowdown”.

“Longer term challenges to sustained and shared prosperity are becoming more visible,” it warns. Officials clearly don’t want to offend their hosts.

We are losing ground in securing our future needs and running down our endowments.

Wake up, Australia, tool up, tune in and get to work.

From Monday, most working-age Australians will be back on the job, with students returning to school during the course of the week. The holiday season is over.