Jim Chalmers exudes partisan pedigree and his budget debut is a safety-first, cut-price social and economic down payment ahead of the “hard days” he says are looming for middle Australia.

Labor’s first budget in almost a decade is more Wayne Swan “suburban idealism” than “big picture” Paul Keating reform, while narrative lines are muted with hints of the intimate EQ of Julia Gillard.

While there’s no cash splash for battlers, there are echoes of the party’s glory years under Bob Hawke, with a new housing “Accord” and tricky promises to boost wages after the recent “summit”.

It’s minimalist triumphalism, so the Treasurer won’t scare financial markets with a self-described “solid and sensible” budget.

But look at the fine print: big government is locked in as Canberra’s spending settles at 27 per cent of the economy, a couple of clicks above what it can collect in tax, recalling the loose settings Labor’s original “Razor Gang” confronted in the mid-1980s.

By plugging into the budget machinery Anthony Albanese’s election promises there’s just enough for true believers to keep the faith and for Labor swingers not to plunge into buyer’s remorse.

The Treasurer said the budget “does more than draw a line under the drift, decline and decay that defined” the previous tenants.

But the thought is inescapable: Labor is back and so is its plump taxing and spending, its “postcode” priorities, and its mantra of creating opportunity.

Chalmers, the career crusader, has imbibed the past in his trek through party institutions, but insists he’s not a prisoner of history, vowing to carry the mission “further and forward” than his political mentors.

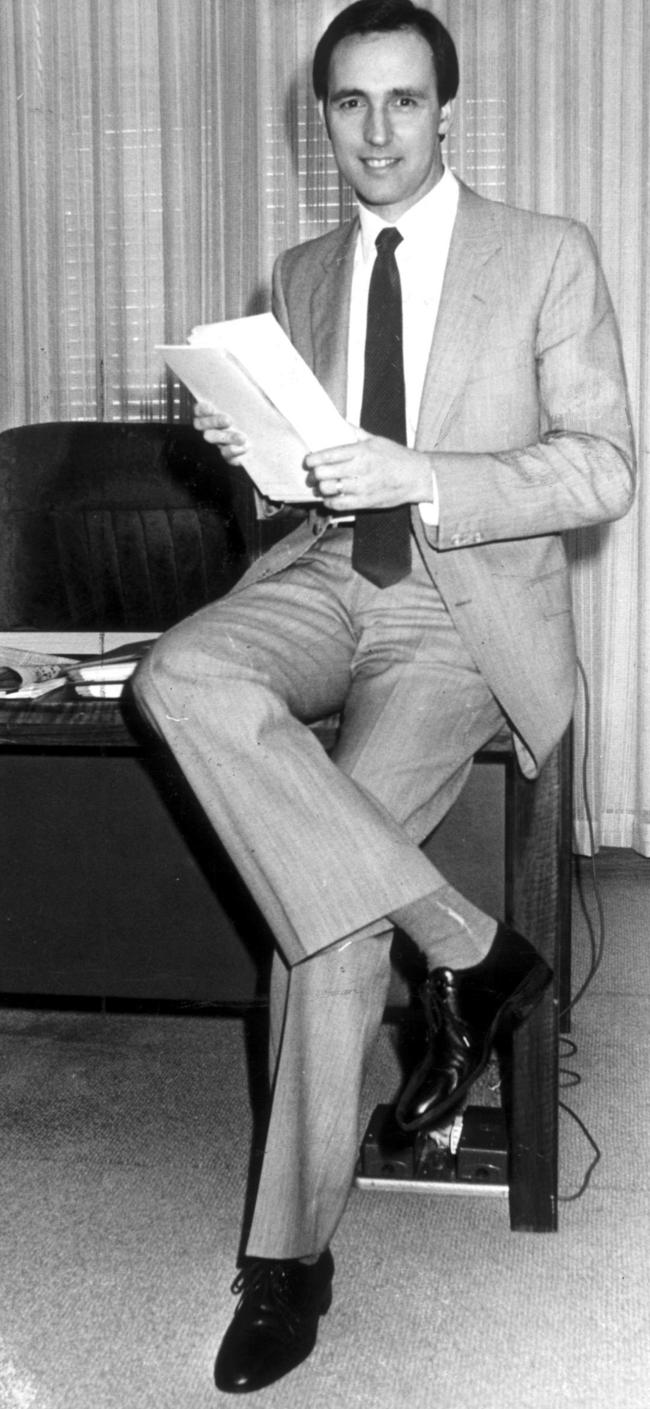

Keating is the acme of Labor treasurers, but in August 1983, at 39 and in his seventh term in parliament, he was finding his feet and voice, as the country emerged from drought and recession.

Hawke had won the March 5 election, but the next day he and Keating were presented with a grim warning from Treasury secretary John Stone about the “truly alarming” state of the budget.

Stone said Labor’s programs would cost $1.8bn, taking the deficit to $12bn, or 6.5 per cent of GDP, “the highest in Australian post-war history”. A flurry of set pieces followed in 1983, akin to the game-plan Albanese Labor has used to drive the agenda since May.

“Hawkeating”, for there was barely a micron of separation in the early days, convinced cabinet and the caucus that some election promises could not be funded, although the new universal health insurance scheme, Medicare, would not be sacrificed.

An economic summit was orchestrated in April, locking in a “consensus” tripartite approach to reform. There was an economic statement in May, followed by Keating’s first budget in August. To trim the deficit, Keating opted for spending cuts rather than tax increases, all the while keeping faith with unions in the new Prices and Incomes Accord. Within a few years, Keating would boast a budget surplus, the first of three, as finance minister Peter Walsh led a ruthless assault on spending.

This year, after a kitchen-table next-day briefing from Treasury chief Steven Kennedy, Chalmers warned of a “dire” budget position, with unfunded programs lurking in the distance.

Yet the final budget outcome for last financial year showed an improvement of $48bn, for an underlying cash deficit of $32bn, equivalent to 1.4 per cent of GDP

Keating toppled Hawke for the leadership in December 1991. With unemployment high and not shifting, Labor launched the February 1992 One Nation package of cash payments, tax cuts, industry assistance and capital works. Six months later, with revenue at its lowest ebb in two decades, and Labor way back in the polls, new treasurer John Dawkins’ budget showed the deficit had doubled the previous year and would come in at $13.4bn for 1992-93.

But the stimulus was introduced too late in the game.

Chalmers did his 100,000-word 2004 doctoral thesis, Brawler Statesman, on Keating as PM, a boyhood hero, whom he still consults from time to time.

One of the brutal lessons of that period was the second, and last, Dawkins budget in 1993.

A day after Keating beat John Hewson at the March election, “the sweetest victory”, Dawkins wanted to ditch the “L-A-W tax cuts” from One Nation. The budget couldn’t afford them and so were messily rejigged: one tranche brought forward, the other pushed back, with hikes in sales tax and fuel excise to offset the cost.

Labor carries scars from the episode, which saw a caucus revolt, marking the beginning of the end for the party’s longest tenure in office. That officially ended on March 2, 1996: the day Chalmers celebrated his 18th birthday, Albanese turned 33 and was elected to parliament, and Swan lost his seat.

It’s a different era, but no less potentially disastrous as Chalmers contemplates the stage-three tax cuts starting in July 2024, which critics say are too costly, how to raise wages and manage a clean-energy transition.

Chalmers was in the treasurer’s backroom for Swan’s first budget in May 2008, spinning reporters about Labor’s hefty surplus and $41bn for three nation-building funds, the biggest of which was to be overseen by new infrastructure minister Anthony Albanese.

We now see the seeds, lightly sprinkled, in the PM’s $15bn National Reconstruction Fund.

In 2008, just like now, the world was closing in, and inflation was a scourge, forecast to average what would seem now as a very acceptable 4 per cent in 2007-08, But it meant the RBA would be doing the heavy lifting to bring down inflation. Swan returned from Washington and, compared with the Kevin07 adrenaline of colleagues, his demeanour was anxious, a sense of foreboding transmitted by global officials and peers about the looming storm.

“Very few commentators understand or acknowledge the turbulent international circumstances we’re experiencing,” Swan told this reporter over a cup of tea on budget morning.

“I hope the people see that we’ve delivered on our election promises,” Swan said, pivoting to the “postcode” pollie Chalmers hopes never to stray far from. “And that we’ve made some tough decisions in this budget that are the right ones for the nation’s long-term future.”

There weren’t many tough decisions by Swan on spending, mainly housekeeping, as in this budget. The sensible part was quarantining the export revenue windfall for the new funds.

At the 2007 election the major parties had promised massive tax cuts and Swan put them into the budget and a little bit more for “working families” and pensioners in a $55bn blitz. There was an end to some of John Howard’s middle-class welfare, with $33bn in cuts to existing programs: Swan as the Great Redistributor.

All up, there was to be a “modest contractionary swing”, Alan Wood concluded in our coverage. “It’s not going to do much to make the RBA’s task easier. It is also true that it could have been much worse, and on its track record in its final years, under the Howard government it would have been.”

Swan’s surpluses never arrived, blown away by the global financial crisis and a revenue drought that stretched through the next few years while Labor’s emergency spending kept rolling long after the tempest had disappeared.

In his 2013 book Glory Daze, an insider’s account of the bruising Rudd-Gillard years and GFC, Chalmers claimed Labor landed the “most successful and best deployed stimulus spending in the world”, yet never got the credit as national sentiment curdled. “How did such a world-beating nation get so down on itself?” he asked.

Now in his fourth term as an MP, Chalmers confronts a world in turmoil, in some ways more treacherous than the times of custodians past who first lit the way and whose legacies are slouching into Labor myth. What’s inevitable, however, are the pregnant storylines about a man on the rise, the would-be financial engineer of opportunity, and what comes next for Australia.

More Coverage