All that is many miles – and as many centuries – away from the tolerance and respect for the freedom of expression that have been among the West’s greatest and most hard-won achievements. But while it should remind us that the clash of civilisations is as real as it is virulent, it would be wrong to ignore the trends imperilling the liberty to think, speak and write in the West itself.

The historical process that secured those liberties was neither simple nor straightforward. Rather, it was, in many respects, paradoxical.

Its most distinctive feature, which separated the West sharply from the Islamic world, was that as of the late 13th century Christian rulers wrested the responsibility to punish blasphemy out of the church’s hands.

Beginning with the reign of Philip IV (“the fair”), who ruled France from 1285 to 1314, the task of repressing “vile speech” – that is, all form of blasphemy – in Western Europe was progressively removed from the ecclesiastical tribunals and vested in the secular authorities.

The shift from religious to secular control hardly promoted freedom; on the contrary, it led to an unparalleled rise in the scale and severity of the repression, whose intensity only increased as the monarchies consolidated their grip over the national territory.

In part, the ferocity reflected the monarchs’ conviction that, as Charles V (Holy Roman Emperor from 1519 to 1556) put it, it was the blasphemers’ sins that called down upon God-fearing peoples “the curse of the Turks”, not to mention earthquakes, floods and plagues. But it mainly reflected the growing predominance of the theory of the divine right of kings, which justified the monarch’s rule as the expression of God’s will. Viewed in the light of that theory, blasphemy, in belittling the divinity, was a direct attack on the monarch’s legitimacy.

The Protestant Reformation, which moved religion to the heart of political contention in the 16th century, along with the explosive growth in printing and the outbreak of the “pamphlet wars” between competing sects, then gave the crackdowns further impetus, while the consolidation of absolutism in the wake of the Reformation increased their effectiveness.

In France, for example, while six royal edicts were issued directing the king’s courts to root out “hideous blasphemy” from 1301 to 1495, there were 20 in the two subsequent centuries – and by the 1620s nearly a third of those accused of blasphemy were being executed, usually after having their ears and lips cut off.

The great French liberal historian Jules Simon was therefore undoubtedly right when he wrote, in 1867, that “it was politics, rather than religion, which made religion so intolerant” in the Christian lands.

However, blasphemy’s unusual status as a religious offence whose repression depended on the secular authorities also proved its undoing, once the factors that had propelled its rise went into decline.

By the end of the 18th century, political authority was viewed as resting on the consent of the governed, rather than as deriving from divine right; the spread, however uneven, of religious toleration undermined the very notion of blasphemy, as it meant there was no single body of doctrine that expression might offend; and the new jurisprudence of the Enlightenment introduced a clear distinction between vice, such as blasphemy, whose avoidance depended on individual conscience, and crime, whose suppression was the proper function of the state.

Attempts to punish blasphemy certainly did not vanish overnight. Nonetheless, after a short-lived repeal of the blasphemy laws in 1791, they were definitely abolished in France in 1881, when future prime minister Georges Clemenceau famously declared “God is fully capable of defending himself; he scarcely needs the French parliament to step in on his behalf.”

Meanwhile, in Britain, the threshold that speech had to meet to amount to blasphemy was steadily increased, with R v Ramsay and Foote (1883) and Bowman v Secular Society Ltd (1917) narrowing the offence’s scope and introducing the requirement – later taken up in Australian law – that the conduct had to be highly likely “to lead to a breach of the peace”.

In those countries and many others, the threat of being persecuted for blasphemy gradually faded into irrelevance, so that by the 1960s the “death of blasphemy law” was assumed to be imminent.

But what the state giveth by way of freedom of expression it has always shown itself capable of taking away. Under the guise of preventing discrimination and deterring “hate speech”, one Western state after the other reintroduced a secular version of the blasphemy offence by the back door.

That the change involved a process of replacement was widely recognised: for example, the UN’s Rabat Plan of Action (2011) recommended that states repeal “stifling” blasphemy laws and instead take “preventive and punitive action to effectively combat incitement to hatred”, including by strengthening the penalties for “expression which encourages discrimination”.

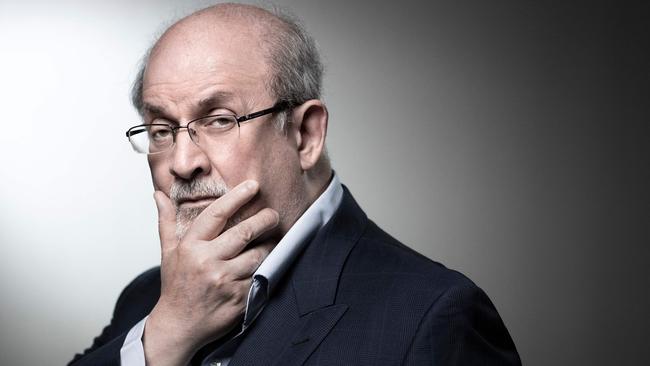

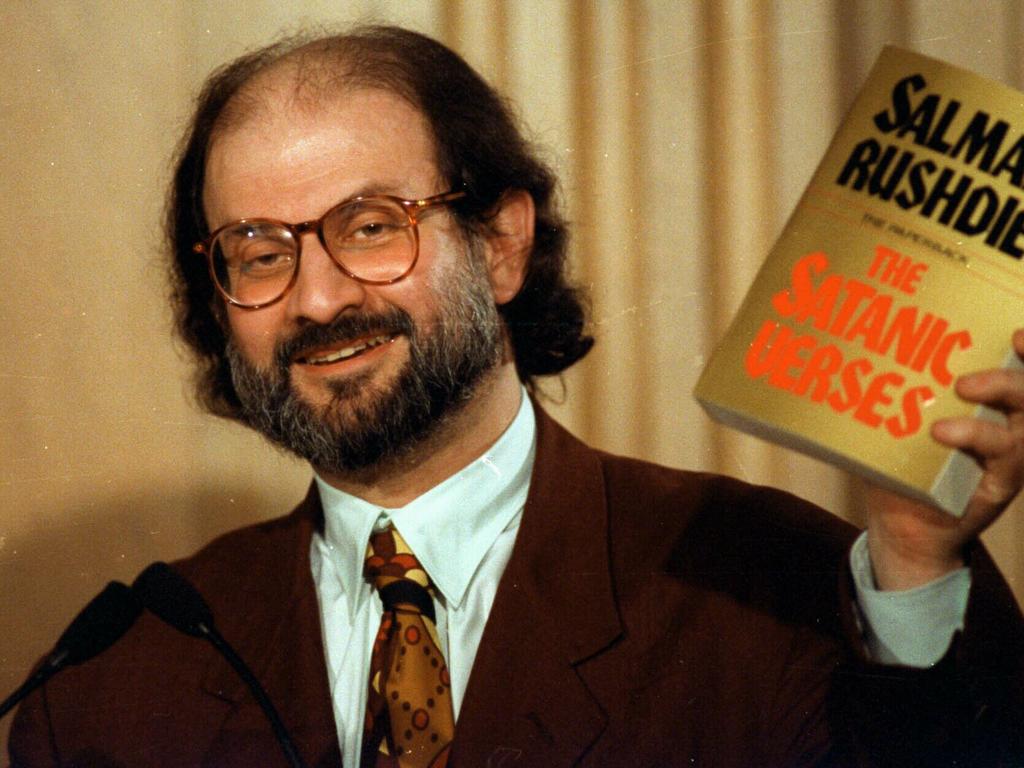

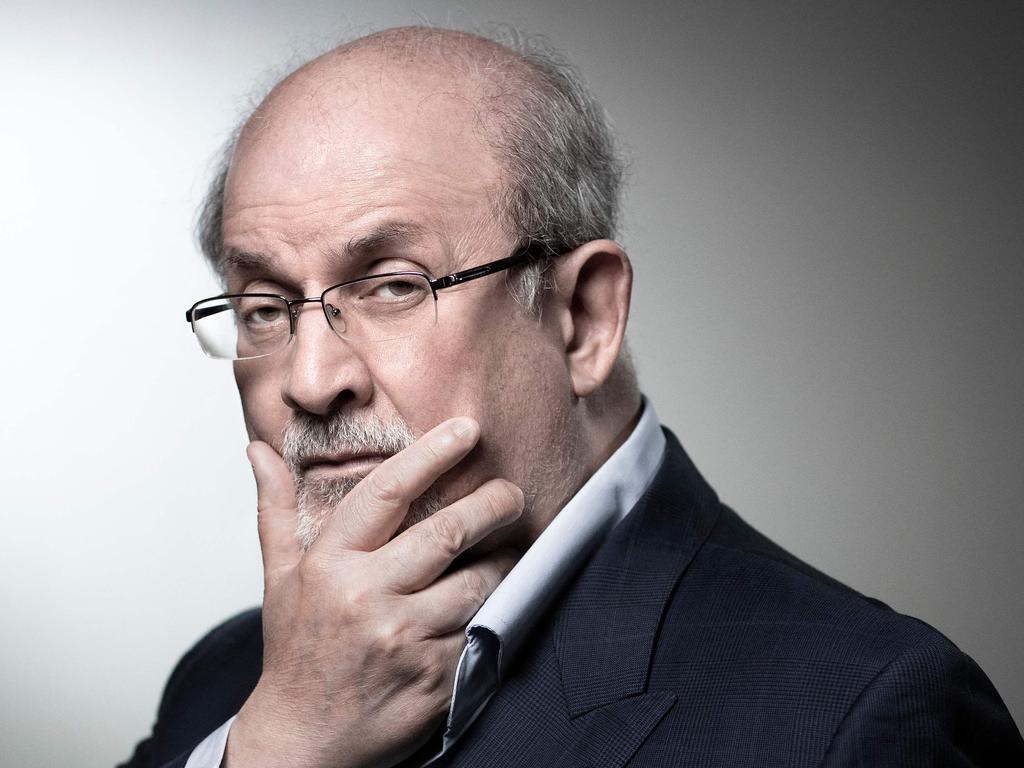

However, it soon became apparent that the only blasphemy the new laws targeted was that offending the dominant moral pieties of the age, with every attempt to tackle issues such as the desirability of gender conversion or to frankly address the threat posed by the Islamism that nearly cost Rushdie his life running the risking of triggering a complaint.

To make things worse, the threshold that had to be met for expression to be regarded as breaching those provisions was significantly lower and more subjective than that which, already a century ago, the courts had imposed on the common law offence of blasphemy.

And further aggravating the harm, the process itself was made into a punishment, as the late, lamented Bill Leak learnt at such high cost.

In his Histories, Herodotus claims that if the Athenians, who were massively outnumbered, managed to defeat the invading Persians at the Battle of Marathon (490BC), opening an East-West political and cultural divide that shaped the ancient and modern worlds, it was because they, and they alone, had secured the right to “frank, free and equal speech” – allowing dangers to be identified, errors to be corrected, and a broadly shared patriotism to be forged.

Now, as the threats we face multiply, the need for “frank, free and equal speech” is greater than ever. We owe it to Rushdie, and to thousands of persecuted writers worldwide, to protect that right – not just from the mullahs but from our own fanatics too.

Last week’s attempt on Salman Rushdie’s life is a grim warning of the danger facing all those who incur the wrath of Islamic fundamentalists. The fatwa condemning Rushdie to death for blasphemy reeks of the darkest aspects of the Middle Ages; by repeatedly praising the attack, Iran’s murderous mullahs have merely confirmed the depths of their medieval obscurantism.