The grubby truth about freedom of speech

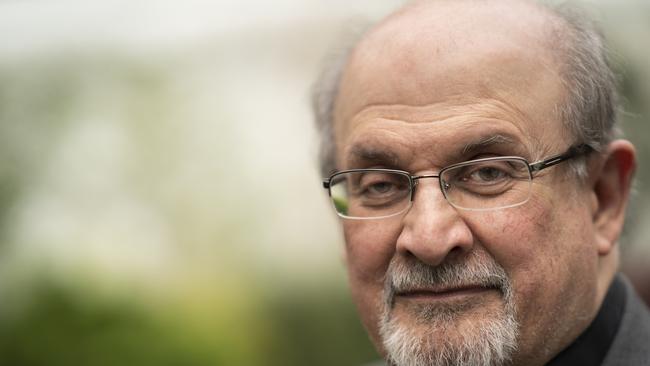

Everybody grasps the wrongness of what happened to Salman Rushdie. But the cause of free speech is rarely so glamorously certain, and may even run contrary to human nature.

Horror – then the consolation of fierce clarity. That Sir Salman Rushdie should have been mutilated with a knife for the sin of writing a novel is an outrage of burning simplicity. Everybody grasps its wrongness. Bevies of quite random celebrities spilt on to the internet to join the frenzy of condemnation that now attends every modern tragedy.

Principled dismay at this assault on the imaginative freedom of writers was issued from unsubtle culture warriors who I am convinced have never so much as glanced at the spines of the self-help books in WH Smith let alone tangled with a work of fiction as elaborate and fantastical as The Satanic Verses. Across the globe, editorial war banners were unfurled: free speech must be defended. Rushdie’s book is a bestseller once again. Floods of new Amazon reviews contain only one word: “solidarity”.

The cause of free speech is rarely so glamorously certain, as was usefully demonstrated by the comedian Jerry Sadowitz who was expelled from the Edinburgh Fringe last weekend for using hateful language and displaying his penis to some in the audience of 600 people.

It will be admitted, I think, that a gulf of artistic achievement separates the exposed phallus of Sadowitz from the contested novels of Rushdie. I know which I would rather defend. But for supporters of free speech, the unsavoury task of constructing a queasy, qualified justification for the unheralded appearance of Sadowitz’s member in an Edinburgh auditorium is the more representative battle. It is a profound mistake to suppose that the fight for free speech is invariably easy or obvious or fashionable.

Few people, I suspect, particularly like free speech, even those who think they do. The managers of the Pleasance Theatre, which banished Sadowitz, issued a breezily paradoxical statement which asserted both that “the Pleasance is a venue that champions freedom of speech” and also that Sadowitz’s material “has no place on the festival”. Similarly, Jacob Rees-Mogg, who imagines himself a haughtily rational free speech libertarian, is campaigning to have the left-wing writer Afua Hirsch banned from Whitehall.

No human society is without taboos. I am persuaded by the arguments of evolutionary psychologists that a tendency to prohibit certain words and acts is an aspect of our fundamental nature, part of the genetic apparatus we evolved to help us bond against outsiders in the groups that were essential to our survival on the distant lion-haunted savannahs of our pre-history. Free speech, I think, is at odds with human nature.

And so, its defenders are doomed to champion an abstract principle against lurid reality. Condemn the unexpected theatrical display of a sexagenarian penis, or the use of a hateful word, and your argument acquires rhetorical immediacy. By contrast, talk of “liberal values” sounds arid and pious. Everyone can see the visceral grotesquery of offence. A liberal society that holds a diversity of opinions and faiths and jokes cannot be seen. It is the very air we breathe. We will only notice it when it disappears and we begin to suffocate.

All attempts to chart free speech end up ill defined and ragged. Outside sweaty west coast libertarian conferences, almost nobody believes in the principle absolutely. There is always a “but": “I believe in free speech but not that people should be free to abuse one another with racial slurs”; “I believe in free speech but not in the right to send death threats online”, to quote a couple of mine.

All the defenders of free speech are ever trying to do is place that “but” a little further out, a maddeningly inexact task that involves counting miniature gradations of irony and grimly weighing up context. Is Sadowitz’s use of racial slurs justified by the “debased, powerless” character he plays on stage? Can we know without seeing his act? To pretend these matters are simple is to invite justified charges of hypocrisy.

“Woke” criticisms of free speech have merit. It is obvious that freedom of speech is not evenly distributed among the population. The speech of a newspaper columnist is clearly more privileged than the speech of someone without that “platform”. It is fatuous to pretend that words cannot cause harm. Even John Stuart Mill thought they could. The argument is not that free speech is a shining and sublimely uncompromised solution to the problem of human communication. Rather that it is, to adapt Churchill on democracy, the worst system “except for all the others we have tried”.

An honest defence of free speech acknowledges that it inflicts pain on vulnerable people, disperses power unequally and has no scientifically identifiable principles – but that it is precious nonetheless. It is a grubby, unfortunate truth.

Has there ever been a less glamorous time to support free speech? Because social media companies refuse to accept editorial responsibilities, the internet is overrun with the gory worst of what humans have to say.

The most vocal modern defenders of free speech are not artists or libertines but pimply “Enlightenment bros” and the talking heads of GB News. Of course, one’s principles should never be formed in accordance with what is and isn’t trendy. So we are left as the awkward, perhaps half-embarrassed, defenders of this unhappy, dysfunctional system which is nevertheless by far the best one we’ve yet devised.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout