As Rushdie explained to GQ magazine in 2005, various cultures have different starting points for someone in his predicament. For example, the respect continental Europeans have for artists is such they would instinctively defend them from attack. Americans, while not having the same reverence for artists, would nonetheless fiercely invoke their constitutional right to freedom of expression.

But in Britain, a pragmatic attitude prevailed, and not for the better. “Rocking the boat is not a good thing,” observed Rushdie. “The fact that I defended my work was called arrogance, whereas anywhere else it might be called principle.”

Rushdie, wrote children’s author Roald Dahl, was a “dangerous opportunist”. The rationale to this accusation was that of a literary poseur oblivious to his irony. “In a civilised world we all have a moral obligation to apply a modicum of censorship to our own work in order to reinforce this principle of free speech,” he told The Times.

Spy novelist John Le Carré declared that “Nobody has a God-given right to insult a great religion.” Australian author Germaine Greer was also indifferent to Rushdie’s fate. “I refuse to sign petitions for that book of his, which was all about his own troubles,” she said. Then Archbishop of Canterbury George Carey said the book “contained an outrageous slur on the Prophet [Muhammad] and so was damaging to the reputation of the faith”.

Hugh Trevor-Roper, a former Regius Professor of History at the University of Oxford, welcomed the possibility of physical retribution. “I would not shed a tear if some British Muslims, deploring his [Rushdie’s] manners, should waylay him in a dark street and seek to improve them,” he wrote. Former Thatcher minister Norman Tebbit labelled Rushdie an “outstanding villain” and decried his “egotistical and self-opinionated attack on the religion into which he was born”.

A survey by the Independent in 1990 found that 30 per cent of British MPs were in favour of banning paperback publication of Rushdie’s book to appease angry protesters. As to the question of whether those who called for Rushdie’s death should be prosecuted, 34 per cent were in the no/undecided category or refused to say.

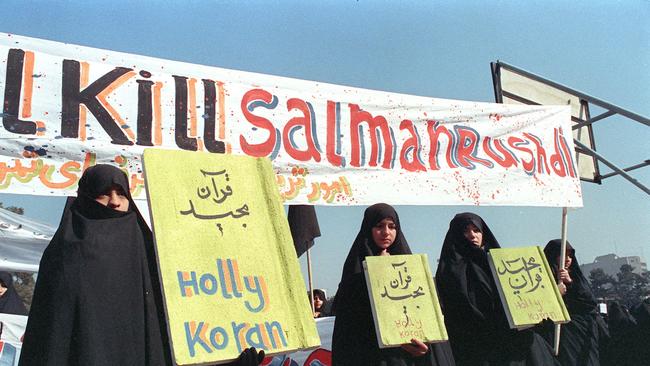

In May 1989 around 20,000 Muslim protesters descended on London, burning copies of the book, assaulting police officers, and demanding Rushdie’s execution. Many of them waved portraits of Ayatollah Khomeini, the Iranian political and religious leader who had earlier that year issued a fatwah calling for the author’s assassination. But as The Guardian observed a year later, the Director of Public Prosecution did not prosecute a single person for incitement in that respect, claiming (laughably) there was insufficient evidence.

A BBC survey of British Muslims conducted in 1989 found that 28 per cent supported the fatwa. Applied to today’s numbers, this percentage equates to around 945,000 people. Small wonder that then University of Oxford chancellor Roy Jenkins wrote that year: “In retrospect we might have been more cautious about allowing the creation in the 1950s of a substantial Muslim community here.” Jenkins, notably, was no reactionary. As Labor Home Secretary in the 1960s, he introduced Britain’s first anti-racial discrimination legislation.

Writing about the affair in the New York Times in 1989, former US president Jimmy Carter lamented that Western nations “had become almost exclusively preoccupied with the author’s rights”. Rushdie, he claimed, “must have anticipated a horrified reaction through the Islamic world”. This was nonsense. Far from turning American public opinion against Rushdie, Carter succeeded only in reminding readers of the weakness and vacillation that defined his one-term presidency.

Elitist resentment of Rushdie in Britain continued for many years. “This is a man who has deeply offended Muslims in a very powerful way,” said Shirley Williams, a former Labour minister and later Liberal Democrats leader in the House of Lords, in 2007. It was “not wise and not very clever to give him a knighthood,” she told a BBC audience, complaining that public resources and funds had been used to protect him from harm.

Also making an appearance at that forum was the legendary writer and orator Christopher Hitchens. “I think that’s a contemptible statement,” he said of Williams, “and I think everyone who applauded it should be thoroughly ashamed of themselves.” As late as 2019 this smug pusillanimity was still evident. “Rushdie’s silly, childish book should be banned under today’s anti-hate legislation,” wrote Independent columnist Sean O’Grady. “It’s no better than racist graffiti on a bus stop.”

The reaction in Australia to The Satanic Verses was low-key compared to that in Britain and the Indian subcontinent. Nevertheless the scenes were ominous. As the Sydney Morning Herald reported in March 1989, about 1000 protesters marched through Sydney in support of Khomeini. “Children as young as 10 wore gowns saying ‘Death to Rushdie’,” the Herald noted.

The reaction was not without dark humour. Writing to the Herald in February 1989, one Zia Ahmad of Sydney – an articulate fellow it must be said – proclaimed his belief that Rushdie deserved to die, provided the sentence was delivered by an Islamic court. “Having said that, I must admit that Iman Khomeini’s public decree sentencing Salman Rush is understandable,” he added. And then in closing: “I am afraid that this whole episode is generating a hate hysteria where Muslims are viewed as bloodthirsty fanatics”. You don’t say?

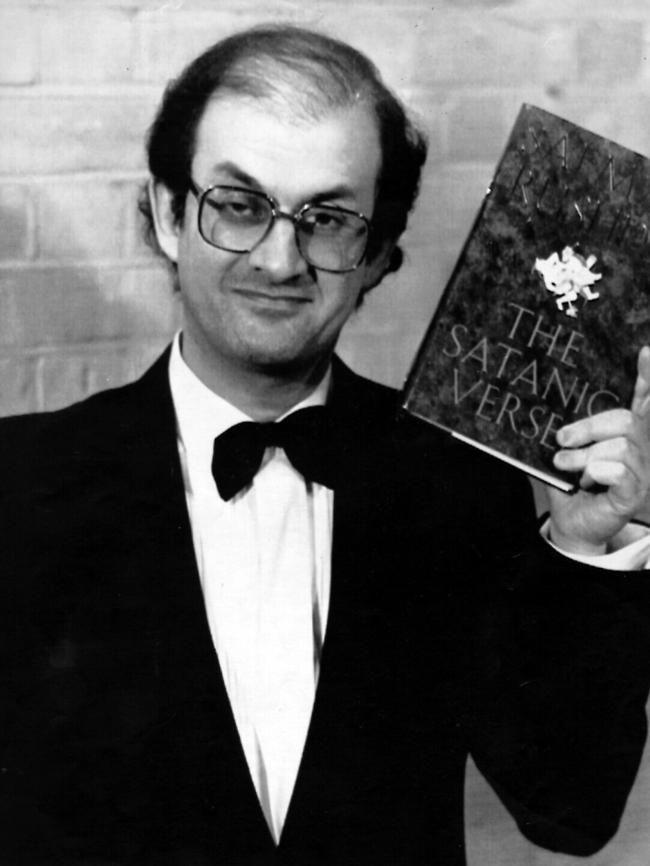

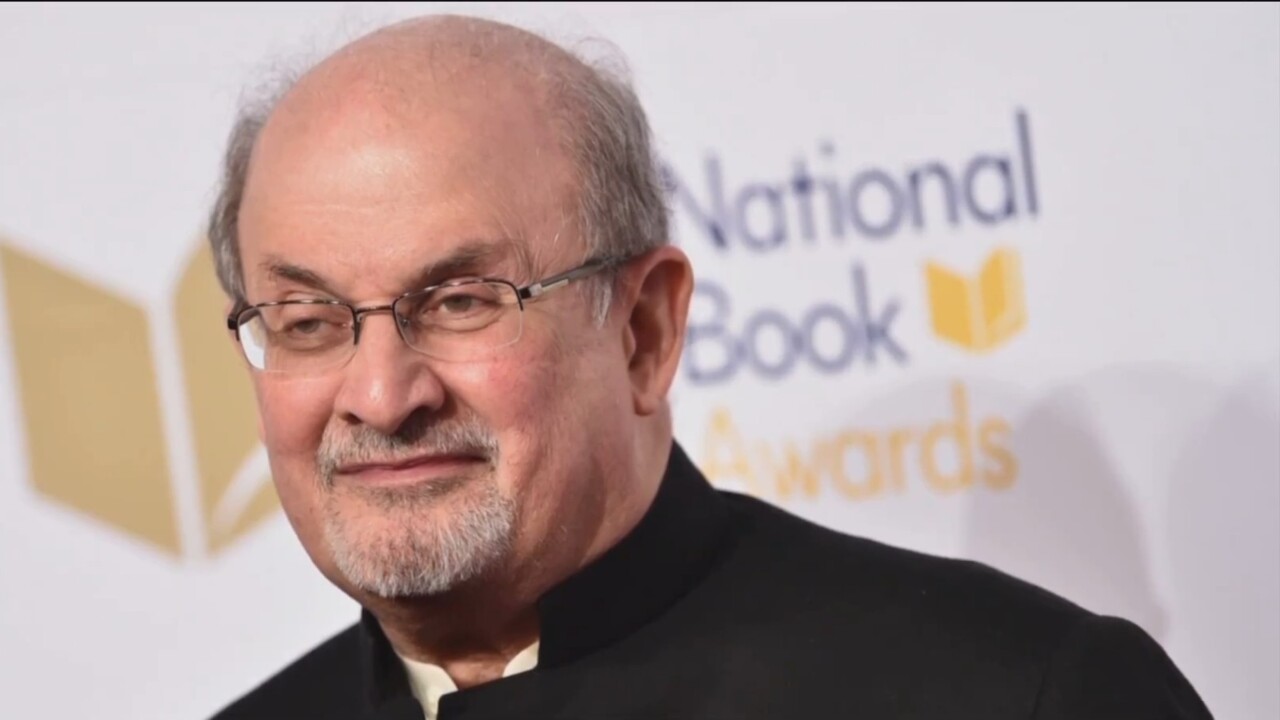

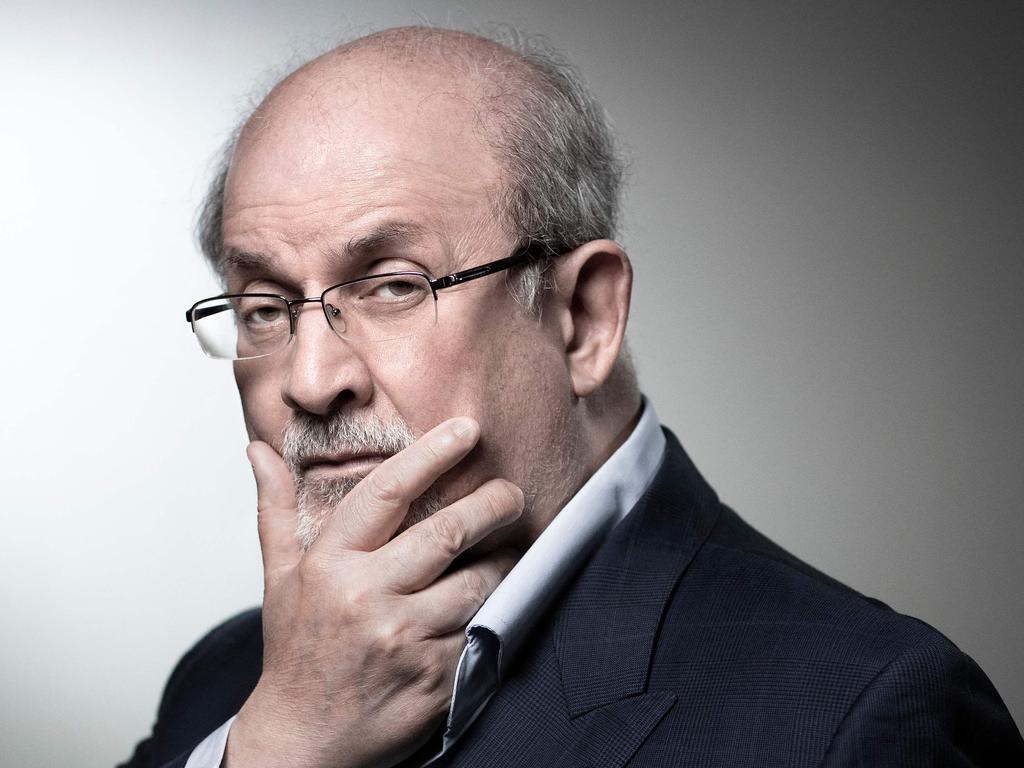

This Friday, hundreds of writers will gather outside the New York Public Library for a public reading of Rushdie’s works, a re-creation of a demonstration held there in 1989 following the announcement of the fatwa. As for Rushdie, the attempted assassination last week in New York state has left him with multiple injuries, severed arm nerves, a damaged liver, and the possible loss of an eye.

Yet despite this, as his son Zafar noted, “his usual feisty and defiant sense of humour remains intact”. Despite being 75 and having spent nearly half his life under a death sentence, Rushdie is still giving fundamentalists and useful idiots the finger.

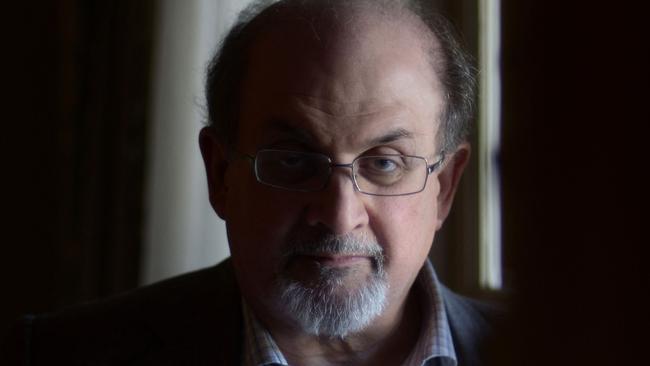

It has been 34 years since Sir Salman Rushdie wrote The Satanic Verses. But as recent events attest, the author, shall we say, still attracts critics. And it is not just the insane reaction of Islamic fundamentalists that he has found hard to comprehend. What truly befuddled him was his treatment by the establishment, a phenomenon he labelled an “English disease”.