This can’t be Salman Rushdie’s last word

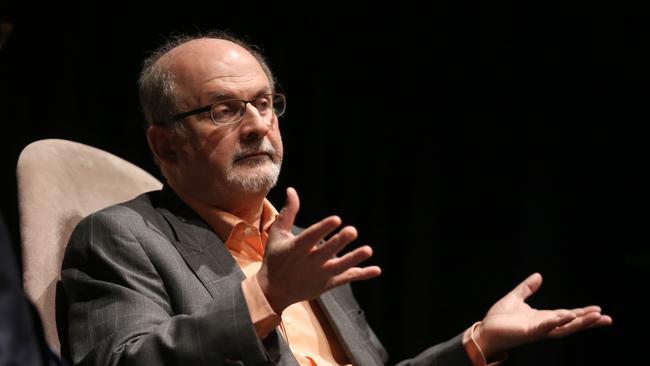

After decades of refusing to be silenced, the celebrated champion of the pen, not sword, has inspired the world of books now left reeling by the attack on his life.

Salman Rushdie was the victim of an assassination attempt on Saturday. In the hours that followed, fellow writer Stephen King offered a near-perfect summation of events: “What kind of asshat stabs a writer anyway? F--ker!”

One imagines an amused Rushdie, 75, putting things rather more elegantly.

Then again, he has for more than 30 years been forced to pay serious mind to precisely that grim question.

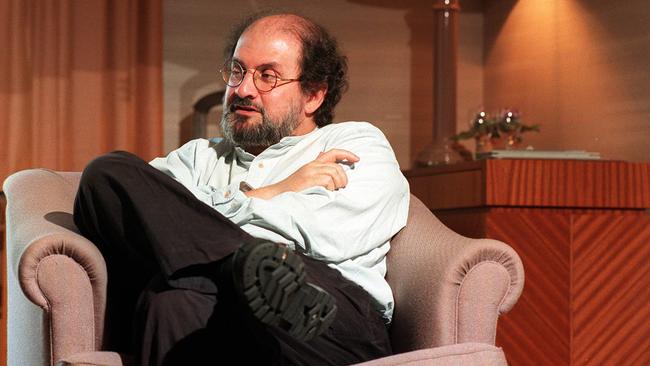

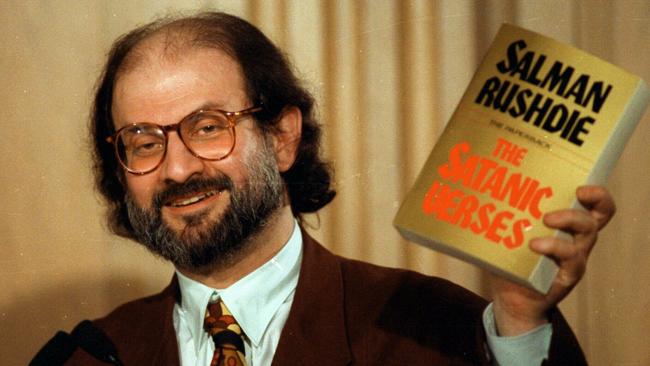

Rushdie has lived with a poisonous, $3m fatwa on his head since 1989, shortly after the publication of his fourth novel, The Satanic Verses.

He was attacked on stage at the Chautauqua Institution in western New York by a man wielding a knife, who went straight for his head and neck.

His agent has said that he is likely to lose an eye. He is breathing, however. And making jokes, which sounds like Rushdie.

The author – that’s all he is, an author, not a fighter, not a soldier – has managed to live with far more humour than most of us could muster. His favourite game is making up book titles that don’t quite work.

Mr Zhivago. That’s one of his. The Big Gatsby was another.

Which is not to say that he did not take the threat to his life seriously. He absolutely did.

When he came to Australia some years ago, publisher Random House went to enormous lengths to ensure his safety.

This is a peaceful country, and many of the people who engaged with Rushdie at the time didn’t quite believe that he needed all the precautions that were put in place. A friend remembered over the weekend how they all turned up at one event to find Cat Stevens’s Peace Train playing as the welcome music.

Shock and horror – the good, fun kind – rippled through the friendly gang of organisers, who raced to turn the music off, while making wide, amused eyes at each other.

A day or so later, Rushdie decided to make a pleasant road trip into the countryside at Milton and somehow got involved in a minor bingle with, of all things, a truck carrying fertiliser, and when the organisers received frantic word, they were like, oh my God, he’s been rammed!

He hadn’t been rammed. He had briefly been on the wrong side of the road. The poor driver was quizzed about Islamic extremism. He didn’t even know who Salman Rushdie was.

Everyone laughed because what a relief, and anyway, surely the threat had passed?

It never passed.

The world of books – readers and writers, people who love the written word – are hoping for Rushdie’s full recovery. He has refused, for three decades, to be silenced. This cannot therefore be the last word.

Many news outlets over the weekend said Rushdie’s books made him a target.

It is completely backward way of looking at things.

Extremists made him a target. He is the victim, not the cause.

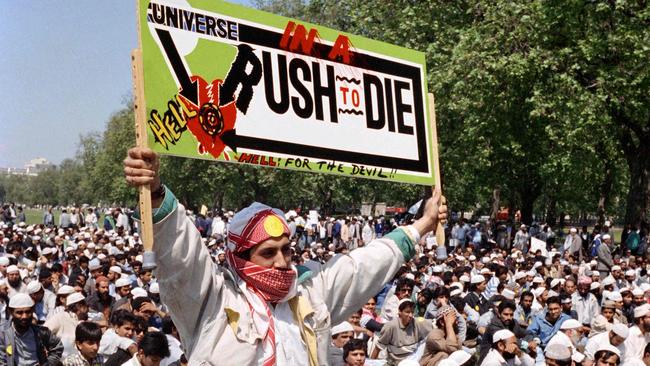

Rushdie, an Indian-born, Booker Prize-winning author, was accused by radical clerics of mocking Islam. Copies of his book were set alight, including on the streets of Britain.

The late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, then supreme leader in Iran, issued the fatwa.

A Japanese translator of his work, Hitoshi Igarashi, was murdered in 1991. The killer in that case also went for the neck.

In 1998, Iran’s reformist president Mohammad Khatami appeared to lift the vendetta, telling reporters at a UN meeting in New York that the threat against Rushdie was “completely over”.

But Khomeini’s successor as Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, said in 2005 that the fatwa was still valid – and he remains in power.

Nonetheless, Rushdie has in recent years lived a little more freely. He visited Australia for a third time in 2014, delighting an Opera House crowd.

His first visit – the one before he got hit by the truck – was with travel journalist Bruce Chatwin in 1984. They climbed what was then known as Ayers Rock, where he heard Azaria Chamberlain’s story. On the flight home, he began taking the notes that became The Satanic Verses.

In New York in the early 2000s, he was a regular at festivals hosted by free-speech group PEN, where he met Caro Llewellyn who is now CEO of Melbourne’s The Wheeler Centre.

“Salman and I worked together for four close years,” she said. “He came to everything, chaired sessions, and made impossible calls when disaster happened.

“Once, we had a 900-seat sold-out event and no author. I rang Salman who called Christopher Hitchens who got on a train from DC straight from the Vanity Fair White House Correspondents Dinner. Christopher would do anything for Salman, and the only thing he asked for when he arrived was some decent scotch.

“We laughed a lot.”

Rushdie served for many years as president of PEN (they are the ones that arrange for the empty chairs to appear on stage at writers’ festivals, to draw attention to writers and poets imprisoned by scared little dictators around the world.)

Chief executive of the American chapter, Suzanne Nossel, said Rushdie had called her just last week to talk about the ways in which they might help Ukrainian writers in need of refuge.

He was passionate in his defence of free speech, saying: “Without the freedom to offend, it ceases to exist.”

Another famous quote from Rushdie: “If you are offended it is your problem, and frankly lots of things offend lots of people … I can walk into a bookshop and point out a number of books that I find very unattractive in what they say. It doesn’t occur to me to burn the bookshop down.”

In Australia, the former academic, now author, Kylie Moore-Gilbert, who was imprisoned in Iran for more than three years, expressed outrage at the attack on Rushdie, upon hearing about it at the Canberra Writers’ Festival.

“I’m utterly shocked,” she told the Australian.

“It is black day for freedom of speech, and a tragic day for literature.”

Video footage of the attack on Rushdie shows volunteers – most of them unarmed, and every one of them a braveheart – surging forward to help.

Just moments earlier, he had received a mighty round of applause for his life’s work, as a champion of free expression. In standing so confidently in front of a roomful of people, it seems that he had allowed himself to hope.

That he might live freely, yes, but that we all might learn to settle our differences peacefully.

This is of course the hope of all mankind, which rests in open hearts, and open minds. Not in violence, but in dialogue. With books and pens, not swords.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout