Rushdie felt safe years after emerging from hiding

Salman Rushdie said he regretted ever going into hiding. Then the long-dormant political firestorm that had once threatened to engulf him reignited.

The long-dormant political firestorm that had once threatened to engulf Sir Salman Rushdie reignited on Friday after the author was stabbed in the neck in New York.

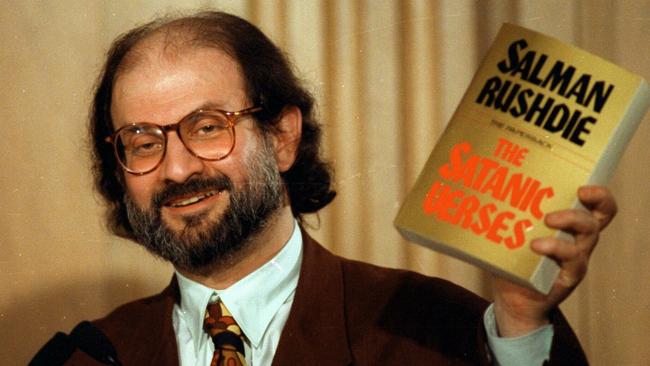

Rushdie, one of the most acclaimed and influential literary figures of his generation, had long ago emerged from the decade he spent in hiding amid the anger provoked by his 1988 novel The Satanic Verses.

He had been accused of blasphemy and Iran’s spiritual leader at the time ordered his assassination with a fatwa, or edict.

The attack before a lecture at the Chautauqua Institution in western New York state was a potent reminder of the lingering threat.

The Satanic Verses, which was critically lauded, featured a prophet named after a derogatory term for Muhammad and named prostitutes after the Prophet’s wives.

In the worldwide protests that followed the book’s publication, 59 people were killed. Bookshops in the UK and US were bombed and the offices of a community newspaper in New York were firebombed in 1989 after the editors defended the right to read Rushdie’s work.

During demonstrations in the UK protesters burnt copies in the streets of Bradford. A small bomb shattered the window of a bookshop owned by the novel’s publisher in York while bombs were also found at Penguin stores in Peterborough, Nottingham and Guildford.

In August 1989 Mustafa Mahmoud Mazeh, a would-be assassin, accidentally blew himself up in a Paddington hotel room while working on a bomb to kill Rushdie.

The novel’s Japanese translator was stabbed to death in 1991 and two years later its Norwegian publisher was shot and seriously injured.

After the controversy Rushdie sought to calm the hostility and released a statement saying: “I profoundly regret the distress that publication has occasioned to sincere followers of Islam.”

However, Iran rejected the conciliatory message. Ayatollah Khomeini had said that even if Rushdie apologised and “became the most pious man of all time, it is incumbent on every Muslim to employ everything he has got, his life and wealth, to send him to Hell”.

Despite the threats, and many of the shops brave enough to stock the book hiding it behind the counter, The Satanic Verses became a bestseller and prompted a debate over free speech in the West.

In 1998 Iran said it no longer supported the fatwa against Rushdie but the threats on his life lingered. He lived with a round-the-clock security detail and moved often.

International travel became almost prohibitively difficult and for many years British Airways said it would not permit Rushdie on its planes because of the danger posed to its staff.

The late Christopher Hitchens, a close friend and supporter of Rushdie, recalled the author staying at his house in Washington for Thanksgiving in 1993 and the accompanying security arrangements of heavily armed guards.

Rushdie is reported to have commented that the situation was “like a bad Salman Rushdie novel”. When it was announced that the writer would be knighted in 2007, a spokesman for the Iranian foreign ministry said that honouring Rushdie, one of “the most detested characters in the Islamic society, is obvious proof of anti-Islamism by ranking British officials”.

A decade ago, a semi-official Iranian religious foundation raised the bounty on Rushdie’s head from $US2.8 million to $US3.3m. The author dismissed the threat at the time. Rushdie also released a 2012 book about his time in hiding, Joseph Anton: a Memoir, after the pseudonym he used.

The book was one of the most eagerly awaited literary events of the decade. While promoting the book, Rushdie said he had no regrets about writing The Satanic Verses.

“I found myself caught up in what you could call a world historical event,” he told The New York Times. “You could say it’s a great political and intellectual event of our time, even a moral event.

“Not the fatwa, but the battle against radical Islam, of which this was one skirmish. There have been arguments made even by liberal-minded people, which seem to me very dangerous, which are basically cultural relativist arguments: we’ve got to let them do this because it’s their culture.

“My view is no. Female circumcision - that’s a bad thing. Killing people because you don’t like their ideas - it’s a bad thing. We have to be able to have a sense of right and wrong which is not diluted by this kind of relativistic argument. And if we don’t, we really have stopped living in a moral universe.”

Rushdie did, however, say he regretted going into hiding and said he should have refused. In 2015 he told The Times that for the past 16 years he had been “walking around the streets for all that time, taking the subway and catching taxis with Muslim taxi drivers”.

A 2019 the BBC claimed the fatwa had been requested by a British Muslim leader. Kalim Siddiqui, who was the director of Britain’s pro-Iranian Muslim Institute, visited Iran before the death threat was declared. He died in 1996.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout