Voters said No to an Indigenous voice to parliament, but Anthony Albanese still isn’t listening

For the Yes campaign, convinced of its righteousness, the only possible explanation for its loss – one of the heaviest in the history of referendums – can be the alleged misinformation being peddled by opponents of the voice.

On full display this week in Canberra has been the Albanese government’s tortured incomprehension at the rejection of what it had pitched as a clear moral imperative and its instinct to carry on regardless, as if the referendum defeat had never happened.

On this page earlier this week, Yes backer Troy Bramston was fair-minded enough to concede some of the errors of the Yes campaign but still accused the No case of propagating “deliberate misinformation … on the political and legal implications of the voice … (with) Trump-like arguments to sow confusion, resentment and fear”. Just because some former judges claimed the voice was legally safe didn’t make it so-called misinformation to cite other former judges who said it wasn’t. And just because some people claimed the voice would be no more than a mere advisory committee didn’t make it misinformation to point out statements by many of its co-authors to the contrary.

People with whom you disagree are not guilty of peddling misinformation simply because they don’t accept an argument or put more weight on some facts than on others. What these anguished assertions are designed to do is to try to delegitimise an unpalatable result.

It’s a common enough tactic from those convinced they’ve been beaten by lesser people and weaker arguments, but it’s fundamentally antithetical to the democratic imperative that a majority of the people, under the Constitution and consistent with respect for fundamental rights, are entitled to have their way. As they did on Saturday, with Yes failing to get more than 40 per cent of the national vote and not one state, not even woke Victoria, to support it.

Sore loser syndrome is not confined to the left – think Donald Trump’s pig-headed insistence the 2020 US presidential election was stolen – but the greater the sanctimony and the assumption of moral and intellectual superiority, the more prevalent is the tendency to disregard the popular vote.

Think of the British establishment’s remoaner response to Brexit and, closer to home, the view of many sanctimonious journalists that only educated people understood the voice, meaning it was the dumb, the dinosaurs and the dickheads who didn’t.

Oozing from every pore of the Albanese government after the weekend’s predictable, but still hard to come to terms with, shock was a desire to change the electorate rather than to change its own policy. Nowhere has this been more evident than in the government’s equivocation over what comes next and whether it’s still committed to the treaty and truth elements of the Uluru trifecta now that the voice has been beaten so comprehensively. (As if anyone gets a trifecta up after losing the first leg but that hasn’t stopped Anthony Albanese from trying.)

Last Saturday night the Prime Minister said he accepted the result, and he agreed that Yes and No voters alike were all Australians, before basically relitigating the Yes case.

Instead of accepting defeat, as prime ministers and opposition leaders routinely must, the main Indigenous Yes backers have declared a week of silent mourning – as if a democratic outcome should ever be mourned – and effectively have shut up shop rather than admit they overreached.

And after saying for many months and declaring on no fewer than 34 occasions that the government was committed to implementing the Uluru Statement from the Heart “in full” – voice first, then treaty, then truth – the Prime Minister seems inclined to push on with the rest of the Uluru agenda, even though it wasn’t just the voice that was rejected on Saturday but the whole separatist mindset that the Uluru statement exemplified. The Prime Minister may think it’s a sign of his political integrity to push on with treaty and truth, via a so-called Makarrata commission, but such hairsplitting is unlikely to impress the 40 per cent of Labor voters who said No to the voice.

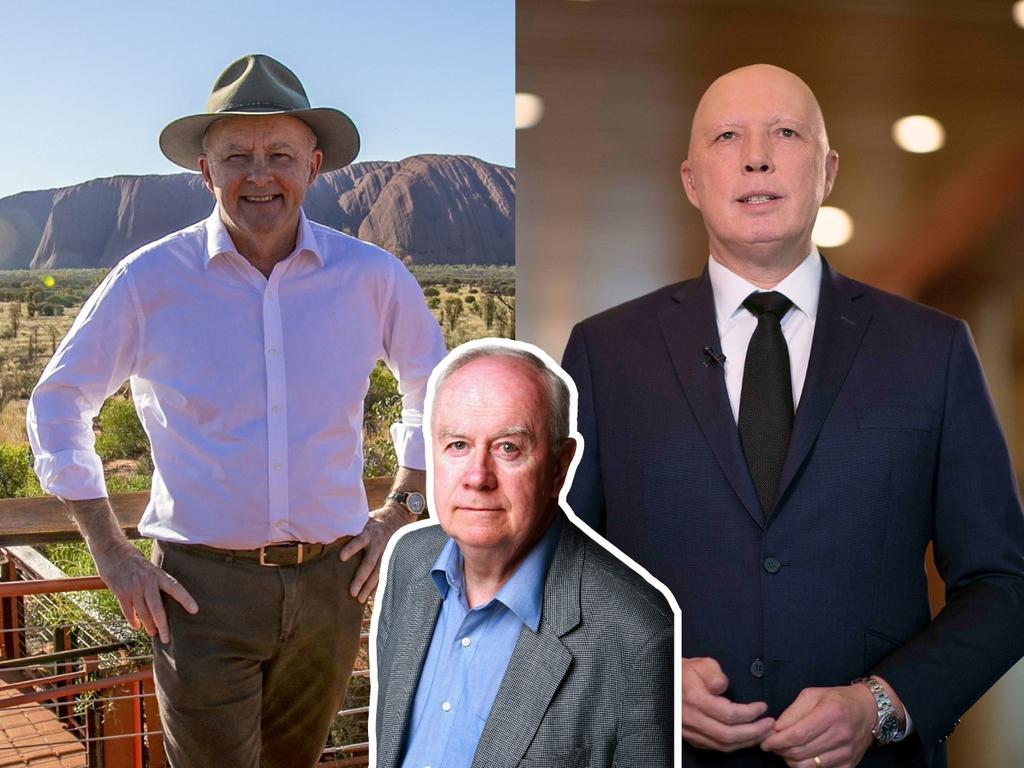

Indeed, almost nothing would maximise Peter Dutton’s chance to make this a one-term government than the Prime Minister again showing he has a tin ear, not just once on the voice but twice on so-called treaty and truth. How can a country make a treaty with its own citizens? And why would any self-respecting country ever set up a so-called truth-telling commission – a kind of official self-flagellation society – to tell a one-sided, jaundiced version of its own history?

Yet it’s hard to see the green-left inside Labor and on the crossbench, let alone the now discredited Aboriginal establishment, giving up on treaty and truth, even if the voice itself is ever so reluctantly surrendered. And unlike a constitutionally entrenched voice that required voter approval, treaty and truth could be proceeded with regardless of the voters – even though, no less than a voice, their impact would be the same separatism that voters have just rejected.

To keep faith with the electorate, the Opposition Leader’s target now has to be the $6m set aside in the last budget to begin the Makarrata process, of which $1m has already been spent, although Indigenous Australians Minister Linda Burney won’t say on what. Without that, the government is likely to get away with implementing the guts of the Uluru statement as if the referendum had never been beaten.

There’s a deeper danger in the obvious attempt to delegitimise the referendum result by insisting it was the result of “misinformation”. Having lost this referendum, mostly through a good social media campaign from Fair Australia, the left won’t want to lose again. Hence the government’s bid to muzzle social media through the coming legislation against so-called misinformation and disinformation.

The Prime Minister’s frenzied insistence that the Uluru statement was just 439 words, not the whole 26 pages spelling out the Makarrata agenda that I reported, is a sign of things to come if this Orwellian bill becomes law. At least for a time, Big Tech blocked my editorials as misinformation even though I was directly quoting key authors of the Uluru statement. The fact the Prime Minister seems determined to proceed with treaty and truth, despite the referendum’s defeat, rather proves my point.

Democracy has worked this time because arguments against the voice couldn’t be suppressed. But if this new online censorship bill passes, future No cases could readily be deplatformed.

Indeed, they may not even get to the point of being cancelled because Big Tech may prevent them from ever being posted lest that attract a heavy fine. This is a deeply sinister piece of legislation and should be junked along with the voice if free speech is to mean anything and our democracy is to remain vigorous.

Last Saturday a strong majority of Australians voted for equality and unity, but that could easily be subverted by a government convinced it has right on its side; and by state Labor governments still set on the voices, the treaties and the truth-telling that a large majority of the Australian people clearly don’t want.

With $400m spent on a referendum the government now wants to ignore, it’s no wonder people are angry.

It’s hard to avoid the conclusion that the Yes campaign can’t really concede that it has lost and doesn’t really accept the legitimacy of its defeat.