Post-referendum traps await leaders in a nation divided over the Indigenous voice to parliament

Democracy empowers and it terminates. The task facing Prime Minister Albanese from Saturday evening will require a new tone and content to bring the nation back together, regardless of whether the Yes or No case prevails – and any compromise on this task will be a grievous mistake.

With polls showing the No case likely to prevail, there are serious traps ahead for both Albanese and Opposition Leader Dutton. Albanese has been astute enough to prepare the ground – if the referendum is defeated he will not legislate the voice. That is the obvious consequence of the options Albanese has taken.

In that case, the voice won’t be in the Constitution and won’t be legislated. Presumably, the idea of a national voice will be finished. The upshot will be immense heartache; but a referendum result is decisive. It comes with a finality. That happens when you choose a referendum.

If Albanese had chosen a different course, he could have informed the Indigenous leaders at the outset he had decided to legislate first – then create a new parliamentary committee to consider and recommend on a model and legislate in his first term knowing he had enough support in the House of Representatives and the Senate. This would have put the Coalition under pressure once the voice was up and running.

Six years ago, on May 31, 2017, on this page, Father Frank Brennan wrote: “Australians will not vote for a constitutional First Nations voice until they have first heard it and seen it in action.” Brennan said the voice should be legislated first so it becomes “an integral part of national policy”.

Why did he say this? Because the voice is a totally new, contentious concept. Its architects and advocates were blind to this reality – but not the public. A singular referendum commitment was an “all or nothing” gamble. Albanese, the Indigenous leaders and lawyers behind the voice were absurdly overconfident. In his weekend Inquirer article, Greg Craven, one of the architects, said their confidence was in “plague proportions” with Indigenous leaders and the legal coterie saying the Yes vote would poll 70 per cent. It was a catastrophic blunder.

At best, it will poll just over 50 per cent and may fall below 40 per cent. It is heresy, but a political truth, that a Yes vote – while a victory for Albanese – will bequeath a litany of political nightmares with the thinnest popular mandate, a divided nation, a split indigenous community and the government having to sort out every policy principle and endless detail about the voice. The conflict will be institutionalised. The heresy that cannot be spoken is that, for Labor, a No vote will come with benefits – the political relief of avoiding such a damaging perpetual dispute.

If the public votes no there are two risks for Albanese: might he wish to continue the battle in some form or another and will he pursue the politics of blame, notably, blaming Dutton for his defeat?

Albanese cannot play both sides in defeat. He cannot say he respects the judgment of the people but also blame Dutton for a defeat that, as PM, he can’t stomach and doesn’t countenance. You can’t fake acceptance of the people’s judgment. Acceptance of the people’s decision must be genuine. This is the big trap for Albanese.

Putting the referendum was his decision. It is Albanese’s responsibility. You put the referendum, you own it. Contrary to his comments, it has been deeply divisive. Everyone knows that. Albanese’s task after the vote is to repair the divisions. Respecting the result won’t be easy. There will be a cavalcade of anger from aggrieved people accusing the No side of everything from misinformation to racism.

Yet what is required in defeat is the humility to grasp one’s own mistakes and realise, finally, the voice was a contentious proposal that broke every rule in the book for a successful referendum. The most astonishing aspect was the dismissal of Labor’s referendum record – one out of 25 successes – that should have meant the utmost prudence and bipartisanship on any referendum proposal.

The trap for Dutton – and his supporters – will be misinterpreting a No result, if that is the outcome. This vote is a one-off about the voice. It is not a vote of confidence or no confidence in Albanese. A referendum loss is not an omen of election defeat for Albanese. The voice won’t be an issue at the next election; it is not a priority for most people.

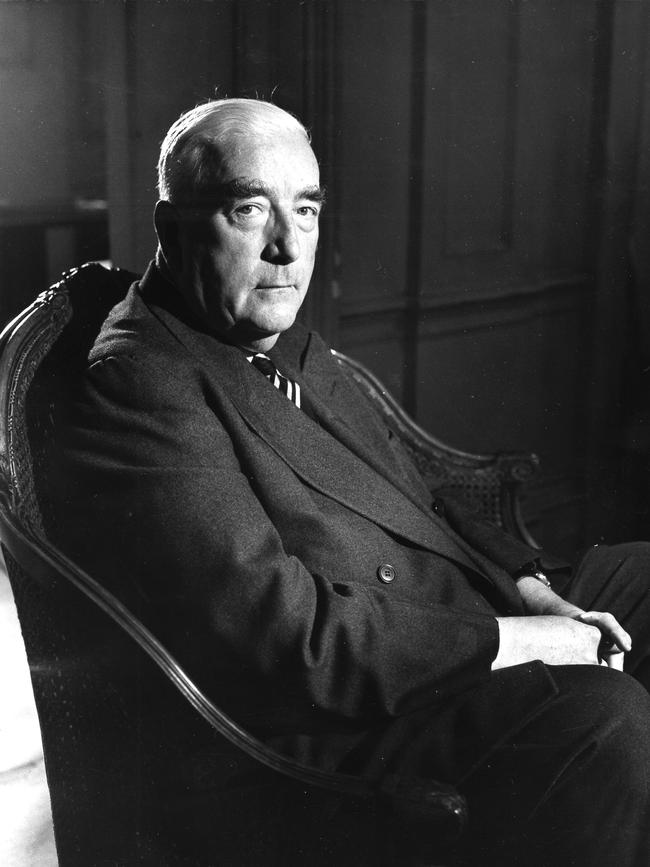

History shows that Bob Menzies and Bob Hawke suffered serious referendum defeats but were hardly affected politically. Referendum results are bad pointers to the next election. Most people soon forget about them. People suggesting the referendum might finish Albanese as PM are talking nonsense. The trap for the Coalition is being lulled into a false conclusion – thinking the referendum alone means a permanently diminished PM.

Newspoll shows the Albanese government heading the Coalition 53-47 per cent in two-partypreferred terms and Albanese heading Dutton 50-33 per cent on the better PM question. Albanese will suffer from a No vote because of damage done to his political judgment. How much damage depends on his post-referendum management.

Probably the main risk flows from the question raised by the referendum: Who does Albanese govern for? He will need to demonstrate to the country that his vision as PM extends far beyond the inner-city progressive class and arrogant institutional elites that became the backbone for the voice. This is the big trap for Labor. Dutton sees his chance – he will say the voice constitutes the defining revelation about Albanese’s political character.

For Dutton, there should be no triumphalism, just respect for the Indigenous peoples who have backed the voice for years and who feel repudiated and let down. Dutton will need to reach out; it will be a test of his empathy. It will be part of the shared leadership story; both Albanese and Dutton will need to devise new machinery, hopefully bipartisan, to navigate the future in Indigenous affairs. They will face an exacting task managing an emotional tide of pent-up resentments after the result.

Dutton will need to dispense with any Liberal government rushing to a recognition referendum. That’s nonsense. After this campaign, the country will need a long referendum break. Dutton, moreover, couldn’t put a referendum without a consultative process that would need to win substantial Indigenous support – that would be years away.

A No vote will be a setback for reconciliation. But it will not be the end of reconciliation. History tells us reconciliation has often been undermined by bitter partisan disputes; witness native title and the apology. Nobody owns the reconciliation pathway. One lesson from the referendum is the depth of political differences among Indigenous peoples and Indigenous leaders. Like the rest of the country, Aboriginal political preferences cannot be categorised by group identity and cannot be stereotyped, though this is often assumed. That damaging mentality is surely finished.

If the No vote prevails Dutton must beware of an emotional resurgence of populist conservatism and far-right elements driven by the false notion the No vote constitutes a cultural and ideological turning point. That’s delusional. It would see the Coalition making a similar historical blunder as Albanese.

Finally, the end of the referendum campaign means Albanese must return to core business – inflation, cost of living, power prices, the energy transition, living standards, government services, real wages and national security – massive structural problems where his government is starting to look unconvincing.

A beaten referendum is yesterday’s political project. It becomes friendless. The idealism and conviction are sucked from the system. After the vote there will be a new politics – Anthony Albanese and Peter Dutton will be driven to new scripts. Hard to imagine now but it will happen.