Referendum on Indigenous recognition wrecked by poor Yes campaign and No camp misinformation

There can be no denying a flawed, poorly organised, badly executed and ineffective Yes campaign. It needed a coherent structure with leadership, authority and responsibility. It apparently used the collective wisdom of geniuses from across the political spectrum but there was little evidence of that.

The campaign lacked a clear message. Having Yes on T-shirts and signs was not an argument. The side could not mount a persuasive case for the referendum or counter those made against it. The cashed-up Yes campaign struggled with online and social media. Television and radio spots were ineffective. There was little billboard and local newspaper advertising, or letterboxed pamphlets.

A streamlined campaign structure and carefully chosen spokespeople with message discipline are critical. There was no effective inoculation strategy – anticipating arguments from the No side – or any effective rapid response. When Marcia Langton equated the No campaign with racism, internal Yes polling nosedived.

Neither can we deny the deliberate misinformation propagated by the No camp on the political and legal implications of the voice. But it did more than raise red herrings. It assaulted the integrity of the Australian Electoral Commission. And it promulgated Trump-like arguments to sow confusion, resentment and fear.

The voice was not radical or risky. It did not challenge the supremacy of parliament. It did not have any veto power, nor could it spend money or run programs. It would not have led to endless litigation in the High Court. It would not insert racial powers into the Constitution; they are already there. And it would not create a new class of citizenship; it was about recognising indigeneity.

Noel Pearson told me he felt betrayed by fairweather friends such as Greg Craven, Julian Leeser and Frank Brennan who supported a constitutionally enshrined advisory body to parliament and government, then opposed it, then supported it. Their arguments against the referendum were weaponised by the No camp.

The No campaign spoke of maintaining the rage and declarations of war. It accused the Yes campaign of being elitist. Yet you cannot get more elite than a frontbench politician (Jacinta Nampijinpa Price) and successful businessman (Nyunggai Warren Mundine.) They too had corporate support with deep pockets. Their arguments were endorsed by reactionary conservatives living in the wealthiest, whitest suburbs of Sydney and Melbourne.

It is true no referendum has succeeded without bipartisan support. It is also true referendums with bipartisan support have not always succeeded.

The Coalition was never going to support a referendum to provide constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians with an advisory body to parliament and government. The Coalition opposed the Uluru statement on the day it was offered in 2017. Malcolm Turnbull rubbished the voice as a third chamber of parliament. So did Barnaby Joyce, then Nationals leader. So did Turnbull’s predecessor, Tony Abbott, and successor, Scott Morrison.

Another fairytale is if Labor legislated the voice the referendum would have had a better chance of success. Hello? Ken Wyatt twice took the voice to cabinet and was rejected by his Coalition colleagues. It never had support in the Coalition joint partyroom in government or opposition. The Coalition would have voted against legislation establishing a voice before a referendum.

So, the argument that Anthony Albanese needed to work harder to secure bipartisanship is nonsense. The opposition was never going to agree to this referendum, however worded. David Littleproud opposed the question before he even knew what it was. Peter Dutton seized an opportunity to inflict political damage on the government. Moreover, recognition without a voice is not what Indigenous leaders wanted.

Should the Prime Minister have convened a constitutional convention? This is not the 1890s. It would have given a platform for the No camp to litigate their arguments against a voice. It would have made no difference. We had constitutional conventions and commissions in the 1940s, ’70s, ’80s and ’90s that made no difference to referendums put and lost by the Curtin, Whitlam, Hawke and Howard governments.

The No campaign has led us nowhere. There was no alternative proposal for alleviating the systemic disadvantage Indigenous Australians face when comparing education, employment, health, housing, justice and safety outcomes with non-Indigenous Australians. The voice would have provided a mechanism to change the interface with government, drawing on experiences and communicating these to policymakers.

Dutton did make one clear commitment to the people if he led the Coalition to power: he would hold a referendum on constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians without a voice. Well, he has now backflipped on that proposal. It was trickery and deception on a grand scale.

Albanese will not suffer long-term damage. Sure, there will be a short-term loss of prestige in having lost a referendum. But he will be respected for standing up for his convictions and accepting the verdict, as we all must. Those prime ministers who lost referendums they advocated but won re-election include John Howard, Bob Hawke, Malcolm Fraser, Gough Whitlam and Robert Menzies.

There is little point in learning lessons from the defeat of the voice referendum because there will not be another referendum any time soon, perhaps for decades, but probably never. The same goes for the dream of an Australian republic. That too has been a casualty.

Poor fellow my country.

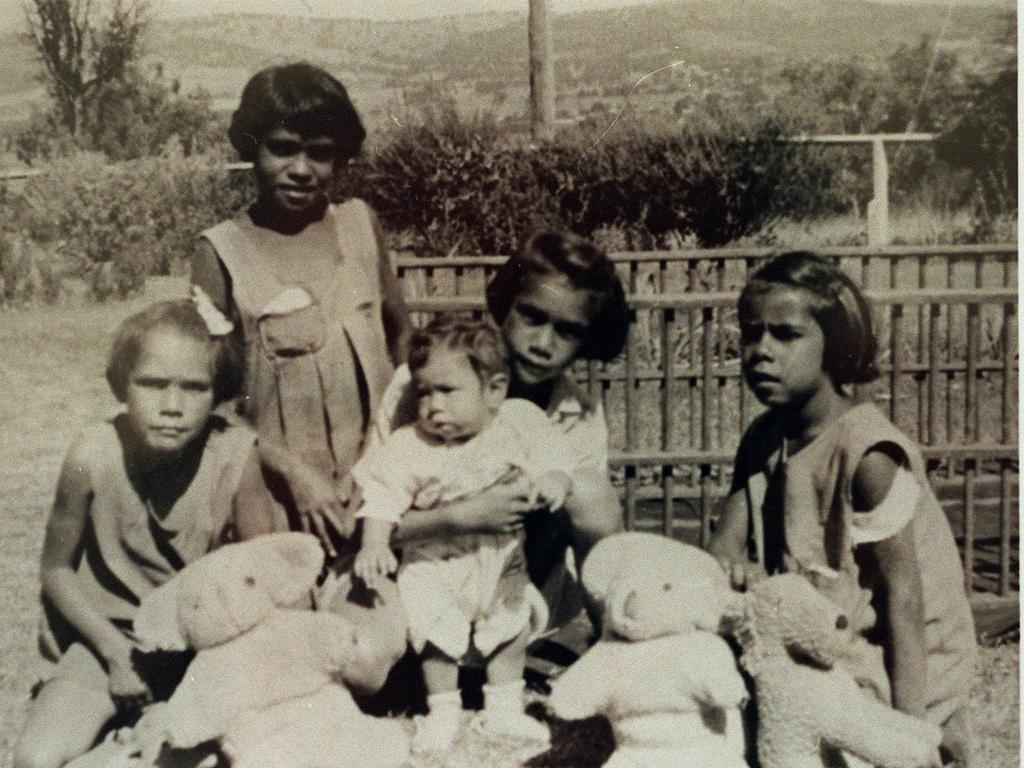

The defeat of the referendum to recognise Indigenous Australians in the Constitution is a tragedy for Australia. Indigenous people voting in remote and regional areas overwhelmingly voted Yes while the nation overall voted No. We now have no pathway for recognition or reconciliation, or a strategy to alleviate entrenched disadvantage.