Voting Yes for the voice is about hope, opportunity, and a better and brighter future for all Australians

The referendum to recognise Indigenous Australians with a voice advisory body would affirm our faith in a better and brighter future for all Australians.

Robert Menzies likened winning support for a referendum to one of the 12 Labours of Hercules. He should know because in September 1951, his proposal to ban the Communist Party failed. He never championed another referendum, despite several proposals considered by cabinet and parliament, over his next 14 years in office.

Menzies is one of many prime ministers who failed to amend the Constitution. Harold Holt, Gough Whitlam, Malcolm Fraser, Bob Hawke and John Howard all lost referendums they advocated. Howard did not support the republic referendum but campaigned for his preamble to the Constitution, which included recognition of Indigenous Australians, in November 1999.

Labor’s track record of achieving constitutional change is not good. Whitlam and Hawke both put six referendums and lost them all. John Curtin, Australia’s most popular prime minister, was also unsuccessful with his 14 powers referendum to guide post-war reconstruction in August 1944. The last successful referendum proposed by Labor was on social services during Ben Chifley’s government in September 1946.

The challenge for Anthony Albanese was always going to be daunting. Yet he took up the proposal in the Uluru Statement from the Heart (2017) to recognise Indigenous Australians in the Constitution with an advisory body to parliament and government, known as the voice. This was a generous proposal extended to all Australians to walk with them on a journey of reconciliation.

But the prospect for this referendum being carried, meeting the high bar of a majority of voters and a majority of states, is slim. Success cannot be ruled out – and there are signs in published and private polling that the Yes camp has clawed back support after a somewhat ill-disciplined and unfocused campaign – but it would require an intervention from the Greek God to be adopted.

If this referendum fails, it is nonsense to suggest Albanese will suffer significant long-term damage to his standing. His prestige will be diminished in the short-term. But his determination and conviction in standing up for his principles will be respected by voters. Taking a stand for unpopular causes was Howard’s stock-in-trade. He was known as the conviction leader.

This referendum deserves support. It would recognise that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders were the first peoples on this continent, with a continuous culture and tradition dating back more than 60,000 years, in the founding document of the nation. This is about showing respect for, and being proud of, sharing this continent with them.

The voice to parliament and government would be an advisory body, made up of Indigenous Australians chosen by their communities, able to make representations on policy matters that affect Indigenous Australians. It is a tragedy that the education, employment, health, housing, justice and safety outcomes for Indigenous Australians are far worse than for non-Indigenous Australians. We must close this gap.

We are more likely to make progress in alleviating this entrenched disadvantage if Indigenous Australians have a seat at the decision-making table. This is what the voice provides: a mechanism that is community-led and empowering, changing the interface with government. They can share lived experiences of what works and does not work with politicians and bureaucrats. The voice can only make suggestions on policy; it would not have a veto power or be able to spend money or deliver programs.

It is not radical or risky. It would not open up the litigation floodgates to the High Court, as the nation’s finest legal scholars agree. It would not challenge the supremacy of parliament, which would have the power to determine the “composition, functions, powers and procedures” of the voice.

It would not divide us by race or citizenship; we already recognise the special status of Indigenous Australians in legal judgments, laws and policies.

Moreover, the Constitution already has race-based powers in sections 25 and 51 (xxvi).

This straightforward and modest proposal, put forward by Indigenous Australians in a spirit of goodwill, holds the promise of systematically improving policy outcomes. Importantly, it would strengthen accountability and transparency in decision-making concerning policies for Indigenous Australians.

Every Yes vote is a vote for better lives and a better future. A No vote is a vote for nothing to change, which gets us nowhere.

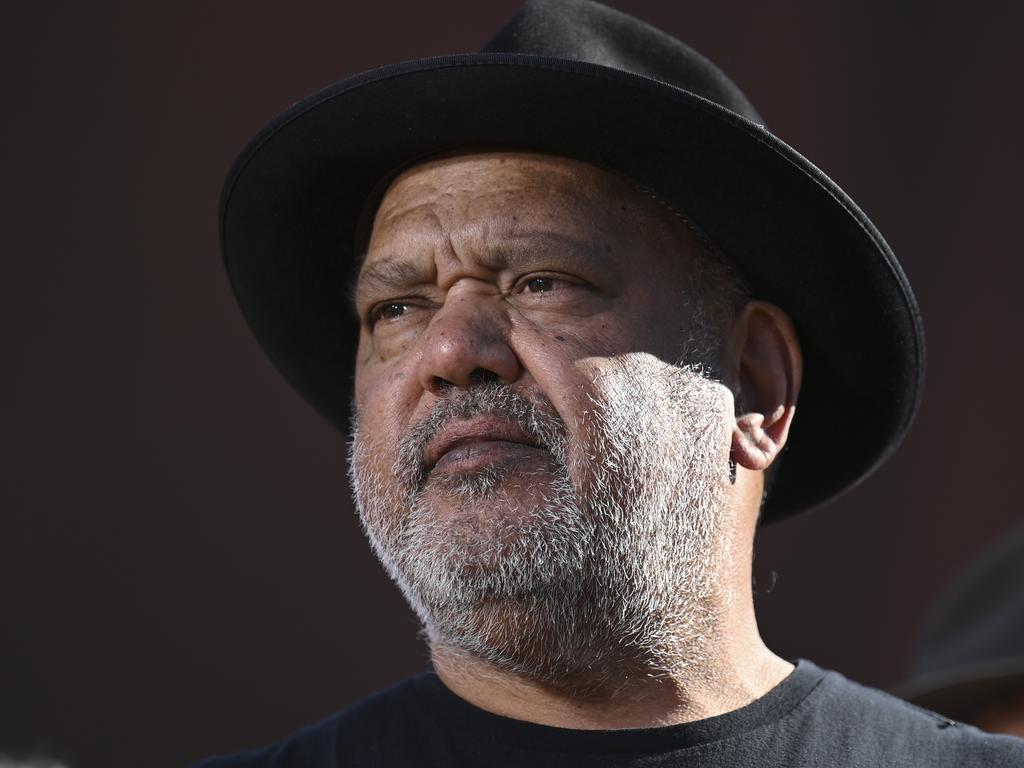

If the referendum fails, Albanese must identify a path forward for reconciliation. Voice architect Noel Pearson says there is no Plan B. He is right – about that because the No camp, led by Warren Mundine and Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, offer no alternative proposal for recognition and improving Indigenous lives. But Australia cannot walk away from the vital need to reconcile a nation and improve policy outcomes for Indigenous Australians

As Australians vote on the most important constitutional referendum in a generation, writing Yes is choosing hope over fear, reconciliation over division, and for a new era of justice and opportunity for Indigenous Australians. Voting Yes is affirming our faith in a brighter future, building and enlarging our nation, and walking together as one. It is about the soul of the nation. This is a turning point for Australia. The choice is ours. We must vote Yes.

Achieving constitutional change in Australia, whether initiated by a Labor or Coalition government, has never been easy. Since 1901, just eight out of 44 referendums proposed have been supported by a majority of voters and a majority of states. Polls suggest the 45th proposal is doomed to fail on Saturday.