Indigenous voice to parliament or not, the real work is still to be done

If the voice is defeated, the PM should proceed regardless with his bipartisan committee. We cannot contemplate a party-political divide on this issue again.

Whatever happens on Saturday night, we will wake on Sunday to an Australia where Indigenous people, on average, are less educated, less healthy and less prosperous than their non-Indigenous compatriots, and more often unemployed, victims of crime, and incarcerated, while living shorter lives.

When Sunday morning comes down, the only difference will be whether we have decided to guarantee Indigenous Australians a non-binding say on how to tackle those problems, and in doing so, recognise them in our national Constitution.

On the ground, across our vast continent, nothing will have changed – the great challenge of removing our deepest national shame, the trauma of Indigenous disadvantage, will remain. But when it comes to reconciliation and Indigenous aspiration, everything will have changed.

Either the goal of a new approach and an Indigenous seat at the table – a fresh and enduring start – will have been embraced by voters and achieved, or the descendants of our original inhabitants will have had their constitutional aspirations repudiated. We never should have left such a momentous navigation of our national story to the vagaries of a hotly contested partisan ballot.

A vote for No will be a vote for the status quo. Despite unanimous agreement that the status quo on Indigenous affairs is deplorable, we will have opted to keep it. Our national leaders, Indigenous and non-Indigenous, political and religious, community and business, defeated and triumphant, will need to respond carefully to the result with a keen sense of national harmony. This will be a challenge, especially when we have seen them manifestly fail to do that during the campaign.

The campaign has been ugly and divisive, generating more heat than light. Both major parties must share the blame.

Anthony Albanese failed to walk the extra mile to try to win the bipartisan support that has been accepted widely as a mandatory pre-condition for referendum success, and the Prime Minister rejected repeated and longstanding calls to provide more detail about how he would legislate a voice, leaving the proposal vulnerable to an unbridled scare campaign. And when those scares came, the Yes campaign failed to debate on the major deceptions; instead of rebutting accusations of racial division and unintended legal consequences, the Yes campaign stuck with a strategy based on the big picture and leftist emotionalism, when it might have been better to switch to a right-of-centre, nuts-and-bolts approach to hold the middle ground. A proposal coasting in the polls at 60-40 or better early in the year gradually fell to around 40-60 and worse.

Peter Dutton, too, never reached out constructively to find a bipartisan compromise. The Opposition Leader clearly did not want it. Not only did Dutton decide to oppose the referendum outright (rather than adopt the liberal option of an open Liberal Party position), he focused his campaign on portraying the voice as racially divisive, which was a self-fulfilling prophecy that has proven volatile and effective.

No one has been more important in this debate than senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price whose personal experience and steadfast advocacy gave credence to a No stance. Also, her very presence on the frontline as an Indigenous woman helped create the perception of Indigenous ambivalence and provided cover for non-Indigenous conservatives to run hard lines.

In the unlikely event that the referendum succeeds, the path forward is clear enough, although not easy. Albanese would need to form the bipartisan parliamentary committee he promised, with Labor and Liberal co-chairs, to negotiate the legislative detail, liaise with Indigenous leaders and oversee the implementation of a voice that will need to include and complement local, regional and state voices.

Much of the groundwork has been done though the “co-design” process undertaken by Scott Morrison’s Coalition government under co-chairs Marcia Langton and Tom Calma (declaration – I was a contributor). Yet the challenges to manage competing interests and organisations, while avoiding duplication and complexity, would be considerable.

More likely, according to all the opinion polls, is that the No case will prevail, and the referendum will be defeated. This presents challenges that are far more nuanced and difficult.

Nothing will have been settled. Not the voice, which the Coalition still promises to legislate; not recognition, which will remain an unrequited national goal; not treaty, which activists will still lobby towards; not truth, with which the national debate will still wrestle; and not reconciliation, which will have broken an axle, but will need a restart somehow, sometime.

The nation will be divided and deflated. Few No voters will be jumping for joy. Many Indigenous Australians will feel rejection at the hands of their fellow citizens.

Indigenous reconciliation is a shared national project that has enjoyed broad support and some success over recent decades, whether through the national Apology, annual Closing the Gap reports and the policies to pursue their targets, widespread embrace of welcomes to country, or other measures to include Indigenous history and culture in the wondrous fabric of our nation. This referendum unavoidably will provide a momentous inflection point in the process of reconciliation: a Yes victory would accelerate it towards a settlement; a No vote, at the least, would pause the process, and possibly threaten abandonment.

Much would rest on the magnanimity of Indigenous leaders. Some of the more experienced advocates could be expected to withdraw from public debate, at least for a period.

The risk for the nation might be radicalisation. After so many years of diligent work in developing a broad Indigenous consensus, negotiating with all sides of politics, presenting a mainstream proposal seemingly capable of winning the middle ground, and campaigning hard for it in an unsuccessful referendum, many Indigenous activists might conclude they have been too conciliatory. Receiving a stiff arm on the voice and effectively being told they have asked for too much, Indigenous leaders might expand their demands rather than reduce them.

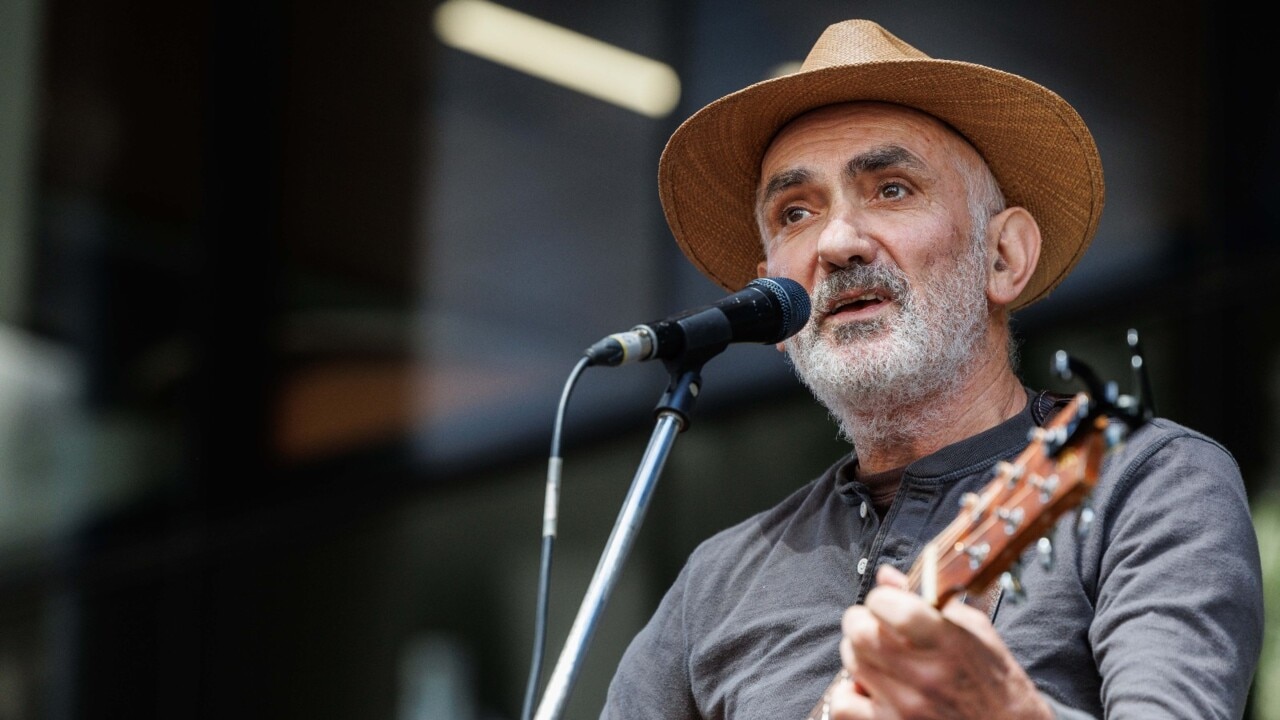

The nation’s unofficial troubadour laureate, Paul Kelly, has sung in favour of a Yes vote, popularising the phrase, “If not now, then when?” Yet if the referendum fails, the question will be if not this, then what?

That is the vacuum into which the nation could fall. Dutton’s glib suggestion we should aspire to symbolic recognition in the Constitution’s preamble takes the debate back to where it started almost two decades ago. It might satisfy his political base, but it will not satisfy the people being recognised.

The nation will need to comprehend the unsatisfactory contradiction of seeking to recognise Indigenous people in a way they have said they do not want to be recognised. We will have to understand that recognising an historically disadvantaged and mistreated minority in a way that asks the majority to contribute nothing, and delivers the minority precisely the same, would not be an act of reconciliation but one of national condescension.

This is all for the future if the proposal in the hands of voters on Saturday is rejected. But it highlights how high the stakes are for national progress and cohesion.

The Prime Minister never should have put the nation on the precipice of this historical fault line. A constitutional change generally requires bipartisanship, and no matter the recalcitrance of the Coalition, Albanese should have worked longer and more assiduously to deliver a major party consensus. It is difficult to resist the conclusion that hubris has played a role.

Albanese overinterpreted the size and significance of his election victory last year and was buoyed by the early polling strength of the voice. Labor was elected, less than emphatically, because it was less underwhelming than a tired Coalition that had churned through three prime ministers in three terms.

Something as significant and complex as the voice could not be expected to succeed if it was stridently opposed by one side of politics. The early polling demonstrated the goodwill of the population and, if it fails, the Yes campaign will have to consider how it squandered that support.

That said, the Coalition has been opportunistic, seizing the referendum as a chance to inflict partisan pain. Its attacks on the proposal have been disingenuous; its central claim that a voice is racially divisive is disproved by its own policy promise to legislate a voice – special forums for Indigenous people cannot be divisive when legislated under a new constitutional power and non-divisive when legislated under an existing power. The Coalition campaigned stridently (and divisively) on the proposition that the voice is racially divisive, while all along it promised to legislate such a body. That it was never properly challenged on this fatal flaw of logic by Labor or the media tells you a lot about the intellectual paucity of this debate.

Constitutional risk was the other central Coalition claim, but it too was exposed by reality. Former High Court chief justices Murray Gleeson and Robert French gave the voice clauses the all clear, as did former High Court judge Kenneth Hayne, the Liberal-appointed Solicitor-General Stephen Donaghue, the overwhelming majority of legal academics and a range of bar associations and law societies.

It was probably French who put it most pithily: “It is low risk for high return.” Yet largely because of the divergent incompetencies or inhibitions of our major parties, in a hyper-partisan environment, the measure looks on track to fail.

Voters always get it right. No matter that the voice could be fairly described as an elegant, effective, and constitutionally safe idea to advance reconciliation in a practical and symbolic way, if it fails the voters will not have been so assured.

The nation has been let down by a Labor government that did not comprehend the vulnerability of a unique idea given to it by a hard-won Indigenous consensus. The government has laboured under the hubristic assumption it could carry a complex reform without workshopping or sharing sufficient detail or contesting the core arguments. In short, Labor has abused the trust of voters and taken them for granted.

Even in the unlikely event the voice eked out a victory, the chance for overwhelming national endorsement will have been reduced to a skin-of-the-teeth and divisive win.

On the other hand, the Coalition should have resisted the temptation of opportunistic partisan mischief-making. It will gain little from this foray, and history may not judge it well. It was prepared to be disingenuous and divisive to defeat a historically significant proposal, just to inflict partisan pain on the government. It should have been constructive and offered a compromise on the wording or structure.

If the voice is defeated, Albanese should proceed regardless with his bipartisan parliamentary committee. Instead of overseeing the establishment of the voice, it would begin the medium-term work of picking up the pieces and finding a bipartisan way forward. We cannot contemplate a party-political divide on such a central strand of our national advancement again.

The real tragedy is magnified when you consider the minuscule differences between the parties – they are 99 per cent politics. Both major parties support a voice, both have done work on a model, both support Indigenous recognition in the Constitution, and both say they are seized by the practical challenge of closing the gap. Yet they have conspired to give us a bitterly divisive referendum campaign. Go figure.

The Uluru Statement from the Heart will not go away, and both sides of politics have subscribed to it in part or whole. Besides, the push for voice, treaty and truth will not disappear, it will simply find new forums and expression.

In the states, legislated voices will be established and begin their work, and in some states negotiations will continue on treaties. There is a danger now that the federal government will surrender its primacy in indigenous affairs as voice, treaty and truth are pursued elsewhere and the states take the lead without national co-ordination.

It appears that as a nation we will have tackled the three Rs of indigenous advancement – reconciliation, recognition and referendum – and failed. Voters, no matter how they vote, are entitled to look at both of our major parties and be despondent at how they have squandered this opportunity.

History will be made on Saturday, one way or the other. And no matter whether the referendum succeeds or fails, this history will test the values, processes and mettle of our political class and our country.