The Yes case for the voice is logical and rational. It’s No that’s confused, inconsistent and incoherent

It is a generous invitation to all Australians, offered in a spirit of reconciliation.

The No case is confused and inconsistent, and offers no coherent alternative that would allow Indigenous Australians to advise policymakers and take responsibility for helping to close the gap on education, employment, health, housing, justice and safety outcomes between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians.

The No case proposes no pathway to achieve both symbolic reconciliation with the First Australians – a proposal first advanced by John Howard in 2007 – and a practical proposal with shared responsibility that would help alleviate the entrenched disadvantage many Indigenous Australians face.

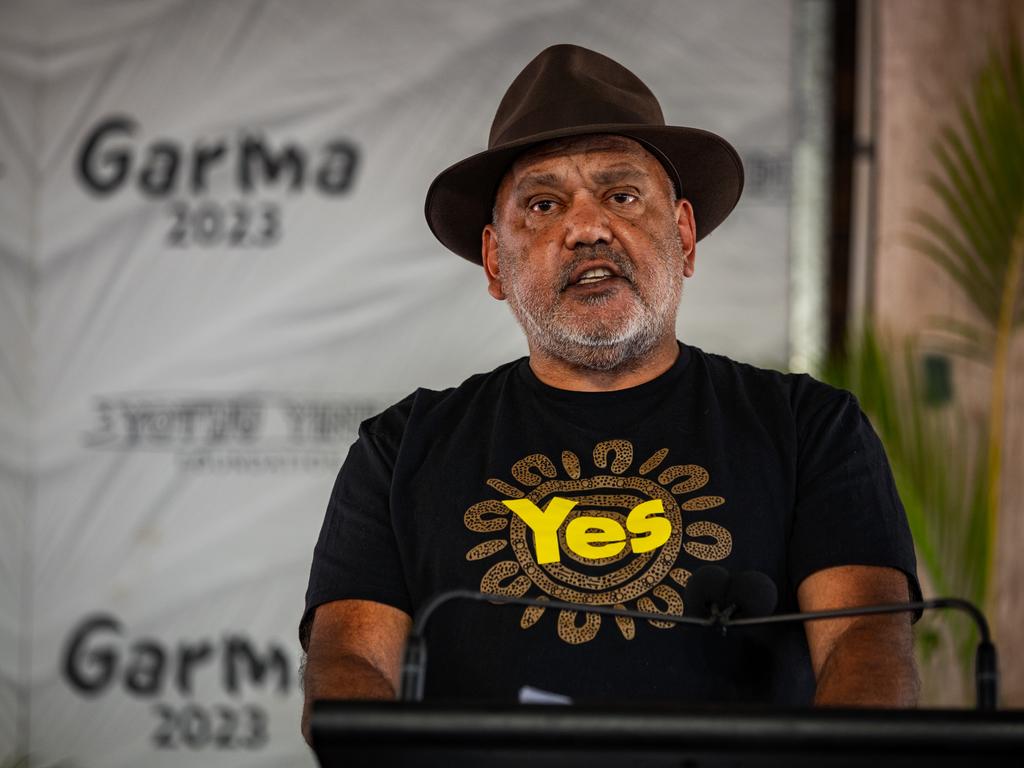

Warren Mundine, the leading spokesman for the No campaign, earlier this year called for a new preamble to the Constitution that would provide symbolic recognition of Indigenous Australians and migrants to Australia. But the idea was slammed by ethnic communities and it has been dropped from the No campaign.

Mundine also favours a treaty between First Nations and the commonwealth. A treaty process is one of the planks of the Uluru Statement from the Heart. Mundine has long made the case for treaties with Indigenous Australians. He suggested every tribal nation should have a treaty with the commonwealth as part of the “constitutional fabric” of a reconciled Australia.

But Peter Dutton, another leading campaigner for the No case, does not favour treaties.

The Liberal Party leader has said treaties would not make any difference to the lives of Indigenous Australians and would result in “billions and billions and billions” of taxpayer dollars being spent by lawyers “sitting around tables in Sydney and Melbourne” negotiating it.

But Dutton does favour legislating local and regional voices to advise the parliament on matters relating to Indigenous Australians. He thinks this would help close the gap. But he does not favour a national voice. Why? He has not offered a convincing explanation why a national voice would not work but local and regional voices would.

However, several Liberal politicians believe Dutton does support a national voice. The Liberal MP for Hughes, Jenny Ware, issued a statement to a newspaper in her southern Sydney electorate in April stating the Liberal Party’s position was threefold: to support constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians; establish local and regional bodies to advise on policy; and also a national voice.

Wait, what? The Liberal MP said the party’s position on a national voice was clear: “a legislated (rather than constitutionally enshrined) national body developed on a bipartisan basis in advance of the referendum”, Ware said. So the Liberal Party supported a national legislated voice. But this is not what Dutton announced.

The confusion among leading proponents of the No case is evident. Moreover, Dutton, as Ware indicated, supports constitutional recognition via a symbolic statement in the Constitution. But a national voice is itself an act of recognition. This is the key part of the voice proposal that they fail to comprehend.

The bafflement in the Coalition is further underscored by the position of Nationals leader David Littleproud. He too is opposing the referendum – he did that even before the wording was announced – but does support constitutional recognition. Littleproud opposes Dutton’s plan for regional voices. He is open to local voices but has not taken a final position on that. It could hardly be more muddled.

Even the Marx Brothers could come to an agreed position. What this means is that if the Coalition wins the next election – a remote prospect – Dutton is unlikely to have the parliamentary numbers required to legislate regional, and quite possibly local, voice structures to advise on closing the gap.

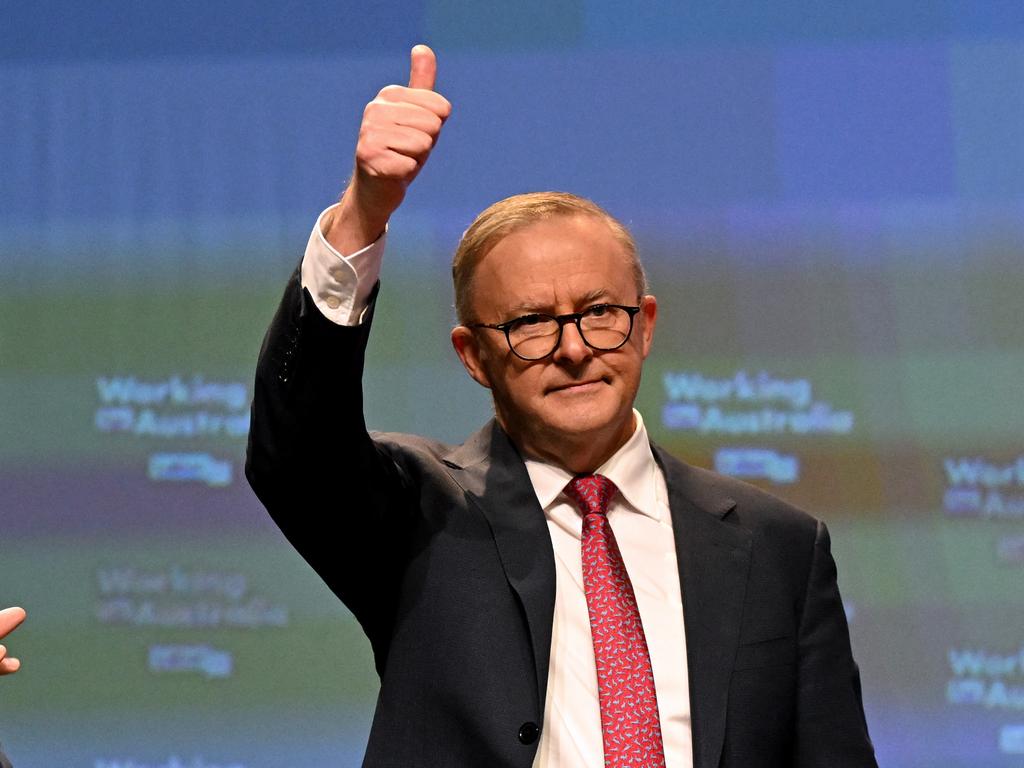

Anthony Albanese has ruled out legislating any voice to parliament – national, regional or local – if the referendum is defeated. He has made the valid point that Indigenous Australians have not asked for this.

They have asked for a head of power to establish a national voice in the constitution. Importantly, the parliament determines how the voice is constituted and how it operates.

There are many red herrings propagated by the No campaign, including that the voice would be akin to a House of Lords with a hierarchy of descent and privilege of origin. This argument has been made by Tony Abbott. The voice to parliament would be no such thing. It would be a representative body of the First Australians and able only to advise policymakers, who can reject the advice.

The only person with a privileged position within government by right of origin is our head of state, King Charles III. The monarchy is a profoundly anti-democratic institution, yet it sits at the apex of our Constitution with its powers nationalised in a vice-regal representative. And if you are privileged enough to live in Tasmania, you get 12 senators for just 400,000 registered voters. In NSW, there are the same number of senators yet 5.5 million voters.

All Australians have a right to make representations to parliament; the referendum would not grant any special rights but it would establish a permanent advisory body for those with a special place on this continent. The High Court, through its Mabo judgment, recognised the legal tradition and cultures of the First Australians.

Nor would the referendum inject race into the Constitution; it has always been there. The 1967 referendum empowered the government to make laws for Indigenous Australians.

At the heart of the No case, riddled with confusion and inconsistency, is a promise of more of the same. The No campaigners offer nothing to improve the lives of Indigenous Australians. Instead, they promulgate fear and misinformation for squalid political purposes. They fail to see the unifying opportunity the referendum holds for all Australians. It is a moment we cannot afford to miss.

The Yes case for the constitutional referendum on a voice to parliament and government could not be more straightforward, logical or rational: it would establish a representative body so Indigenous Australians would provide advice about matters that affected them.