Indigenous voice to parliament opponents taking us down a divisive path

Unlike many issues, the Yes and No cases are not quibbling about detail here. They are going head-to-head with starkly different versions of division – and its first cousin, equality. It is a pity that on this vital issue, the No case is at its least reputable, and indeed divisive.

Far from preventing division, various No supporters fan it for their own purposes. The immediate object is to win the referendum by catalysing the electorate into two fundamentally sundered camps, with the majority scared to death of voting Yes.

But there are darker agendas. Some ideologues use the referendum as a stalking horse for their long-term project of undermining the very concept of Indigenous disadvantage, and even Indigenous character. Within the No side, they are a relatively small but powerful cabal.

On the issue of division, the position of the Yes side – as articulated by Prime Minister Anthony Albanese – has appeal.

Far from dividing, Albanese sees recognition generally and the voice itself as completing the Australian constitutional project.

Broadly put, Australian history has three great strands: British constitutional heritage; the blessed influx of migrants; and our founding Indigenous people.

This last, fundamental component has been devalued. Restoring it only enriches our national story.

It is no wonder this vision has broad appeal. It is the same vision – though not the same constitutional outcome – shared by conservative prime ministers John Howard and Tony Abbott. Its only problem is a faint whiff of philosophy, never helpful in a referendum.

The No case attacks this vision with the aggression and principle of a white pointer. The assault is calculated to provoke a fear that in turn produces profound popular division.

The first strand of argument is clothed in the tatters of constitutional principle. It shrieks the voice will create two classes of citizens by giving Indigenous people vast rights shared by nobody else.

This is untrue. Indigenous citizens will have no new powers or constitutional rights. They will have no differential status. Unlike in Canada and the US, there will be no unique Indigenous privileges. There simply will be a means for Indigenous people to express collective views to Canberra.

If this is an Indigenous Bill of Rights, and I were an Indigenous person, I would demand my money back.

The No case is misleading in maintaining the law never differentiates between groups of people based on disadvantage. Multiple equal opportunity Acts, let alone special laws for disabled people, stand out. Will we repeal them?

Constitutionally, the greatest division and inequality in Australia is that every state gets the same 12 senators, regardless of population. Tasmania gets more places per person than Victoria. This is real power, not a constitutionalised chat. It is irrelevant that it was part of the Federation package. The principle is the same.

The second sickening irony is that there is indeed a dramatic division between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, but it is not constitutional, nor does it favour Indigenous citizens. Indigenous people suffer social and economic disadvantage that would see white Australians rise in armed revolt.

This is the division that grips and chews.

The tragic comedy of the No case is that it vaporises over the divisive unfairness of an advisory voice, but sees no element of division in death, sickness and non-existent opportunity. Of course, they worry about Indigenous health and education. But as a point of bitterly harsh, practical division, they are obtuse. It is the old biblical example of seeing the speck in another’s eye but not noticing the plank in your own.

This is the official currency of the No side. Preaching against division, it divides by pretending to non-Indigenous Australians that Indigenous Australian are getting a cushy, special deal.

Frighteningly, this debate on division is going to get much worse. It is the process of morphing into genuine racial politics.

Until recently, the forces of No have held some of their nastier arguments about division in reserve. It was not out of decency, but a question of timing. As the referendum ripens, these worms emerge. There are two arguments cynically calculated to divide Australian like a medieval religious schism.

The first is that the voice referendum should not be put when “ordinary Australians” are doing it tough. The second, vastly worse, is the mania of the “fake aborigine”, to give it the offensive label of some of its adherents.

The argument around the plight of everyday Australians is dangerous because, as the saying goes, every great lie contains a kernel of truth.

Many Australians are indeed doing it tough. Interest rates are high, wages low, and electricity expensive.

These are circumstances where it is easy to foment resentment against any group seen as receiving an advantage.

This is where the politics of division becomes truly dangerous. By fanning embers of resentment, the No case risks starting a fire of genuine racial sentiment.

Resentment is always a bad base for policy. Logically, one group loses nothing when it is unaffected by modest change assisting some other, profoundly disadvantaged group. Their gain is nobody’s loss.

But as a cynical promotion of division, the politics of grudge is highly attractive. Given encouragement, some proportion of people will feel neglected and disadvantaged by the voice. In practice, these will be Australians most exposed to economic hardship through social background or lack and opportunity.

This is a critical group of voters, whose natural generosity may be undermined by the dog-whistle of division. Their votes will deliver or doom the referendum.

It is notable that the critique of the voice by Opposition Leader Peter Dutton has progressively moved from technical point-scoring toward the politics of division and belaboured battlers. Hip-pocket referendum recrimination has become mainstream.

The argument the voice should be rejected because many Indigenous people are not actually Aboriginal is the most divisive and dangerous in the entire referendum. It was always going to be wheeled out by plausibly deniable fringe-dwellers on the No side.

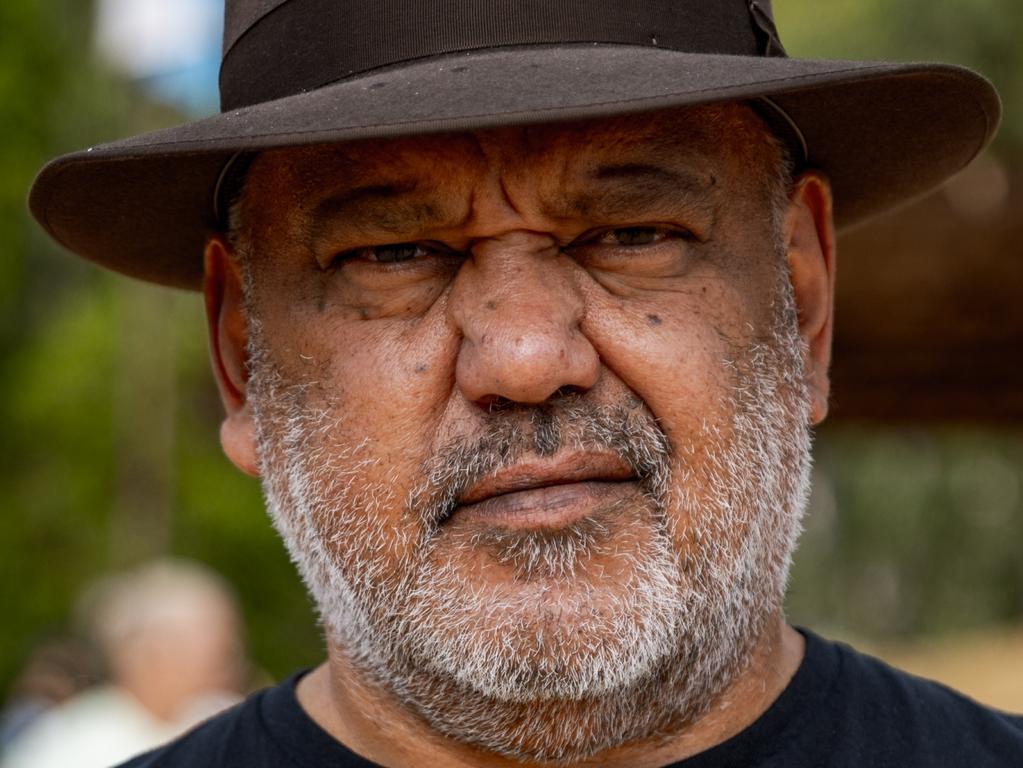

Leading No campaigner Gary Johns fired the first shot. He argues Indigenous people should be DNA tested before they receive government benefits. Johns was and remains a member of the governing committee for Recognise a Better Way, the organisation that leads the No case.

Many Yes supporters hope to ignore this line of argument on the basis that it is just too horrible to contemplate. You can understand the reaction, but they are wrong.

If this calumny is not smashed even before it is fully launched, it will lurk invisibly in the polling booth. Incipient confusion on racial identity can be whipped up by unscrupulous No campaigners into a settled suspicion. It also can be poisonously combined with the politics of resentment. If I am struggling, why are dubious Aborigines getting all the scholarships, the grants, and the jobs?

The Yes case needs to be realistic here. Saccharine optimism aside, racial authenticity is one of the objections most raised on the ground against the voice. Unnervingly, it appears across political, economic and social boundaries.

The entire argument is more than offensive: it is just plain wrong. It typically starts with the proposition “anyone can say they’re an Aborigine”. True. But just because you say you are Indigenous will not mean you are, or anyone thinks you are.

The Australian test for Indigeneity has three parts: ancestry, identification, and acceptance. Forget the first two for the moment. Unless you can get the Indigenous community to accept you as one of theirs, you are out of luck.

This debunks the urban myth of the Bourke Street Aborigine. Why would an Indigenous community accept someone having no connection at all with the Indigenous world? Why, in reality, would it embrace someone who is dubiously one per cent Aboriginal?

True, there has been huge growth in the number of people identifying as Indigenous in the census. But there also are plenty of people declaring their religious identity as “Jedi”.

You can enjoy describing yourself as an Indigenous person without ever actually getting to be one. It is a bit like me. I proudly identify as an Irish Australian. I have a profound connection to Ireland, especially the ancestral village of Annaghdown in County Galway. A majority of my DNA is Irish. But that does not make me an Irish citizen, nor is there any way I could acquire that status.

The vilest and most stupid version of this race politics is photographic. Look at all these fair-skinned Aborigines. They must be frauds, right?

Yet as any secondary science student knows, appearance is randomly dependent on different genetic inheritance. Two cousins from the same family including both Indigenous and non-Indigenous ancestors can look completely different, one “black” and the other “white”. Just as my brother resembles a superannuated Spanish pirate while I am a plain honest Celt.

But momentarily take this grubby nonsense seriously. Look at any photo of the 30-odd members of the Indigenous Working Group on the referendum. How many of these eminent Australians could you swear on your children’s lives to type on appearance as non-Indigenous? Or can you scientifically sort our Indigenous members of parliament: Lynda Burney; Malarndirri McCarthy; Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, for God’s sake?

We must decry this political phrenology, and any other argument designed to divide us by race. If political disunity is death, racial disunity is disgrace.

Emeritus Professor Greg Craven is a constitutional lawyer.

The issue of division is a win or lose battlefield in the voice referendum. Many Australians will cast their vote on whether the voice will unite or divide the country.