Why PM is right not to delay the referendum for an Indigenous voice to parliament

Liberal MP Andrew Bragg says the vote should be put off to mid-2024 because more time is needed “to save the concept”. NSW Liberal leader Mark Speakman will also vote yes, but believes there should be separate questions on constitutional recognition of Indigenous Australians and establishing the voice. Independent senator Lidia Thorpe has gone further in saying the referendum is mere “window-dressing” and should be cancelled.

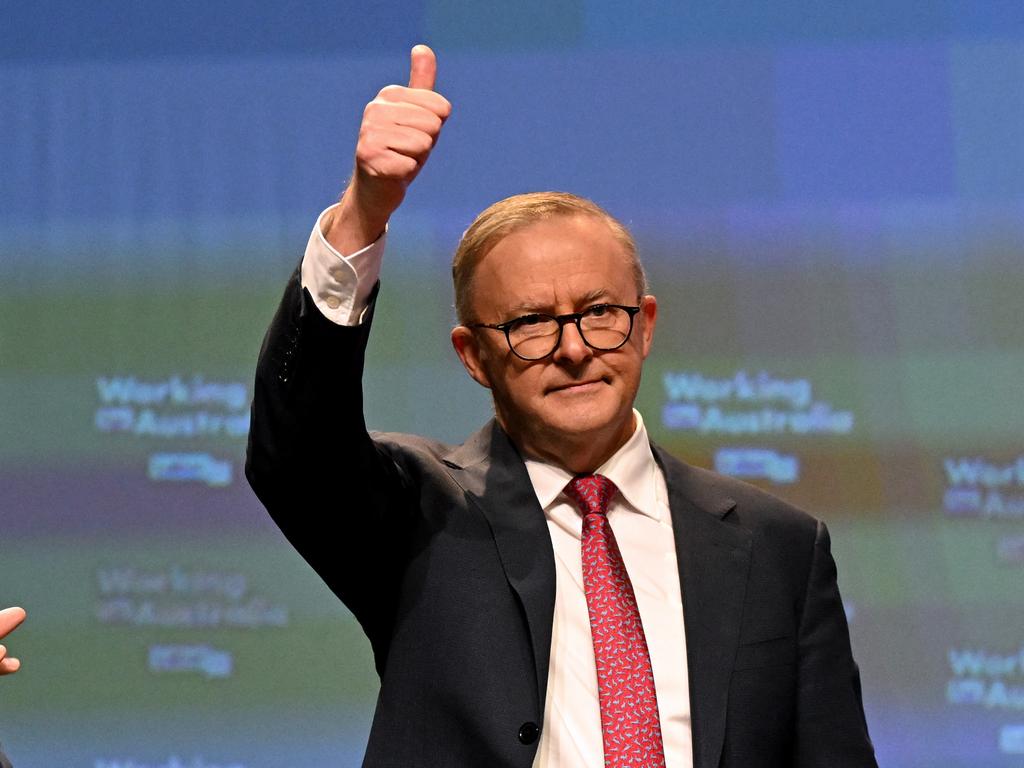

But after Anthony Albanese’s call to arms at the ALP national conference last week, it is clear none of these things will happen: Australia is on an inexorable path to a single-question referendum on the voice, most likely on October 14.

Once a proposal is passed by parliament, the Constitution is unequivocal. The proposal “shall be submitted in each state and territory to the electors qualified to vote for the election of members of the House of Representatives”.

This must occur “not less than two nor more than six months” after its passage through parliament. A referendum on the voice must be held between August 19 and December 19 this year.

Despite the clear words of the Constitution, past practice has been inconsistent. Proposals to change the Constitution were passed by parliament in 1915, 1965, 1983 and 2013 but were never put to the people.

In 1915, the Hughes government sought war powers by referendum, but this became unnecessary when the states referred the powers to the commonwealth.

In 1965, the government changed its mind about holding a referendum because incoming prime minister Harold Holt was less supportive of the proposals than outgoing prime minister Sir Robert Menzies. In 1983, the Hawke government deferred some of the proposals until 1984. These failures to hold a referendum may not have been constitutionally permitted, but they occurred nonetheless. No High Court challenge was brought.

The closest Australia has come to a referendum over recent years was in 2013 on recognising local government in the Constitution. The Gillard government sought to hold the referendum simultaneously with a federal election on September 14, 2013.

Unusually, the prime minister announced the date of the election eight months prior in January 2013. Things began to fall apart when the states showed little enthusiasm. Victoria flatly refused to support the proposal, NSW did not express a view either way and most of the remaining states expressed reservations about a curtailment of their power.

Even more problematic was the furore that arose over the allocation of funding to the Yes and No cases. After parliament suspended limits on referendum expenditure, the Gillard government resolved to fund the campaigns according to the proportion of parliamentarians voting for and against the constitutional reform. The bill attracted strong support across all parties, with 95 per cent of parliamentarians voting yes. This meant that, of the pool of $10.5m, $10m went to the Yes campaign and $500,000 to the No case.

This provoked an immediate outcry. Coalition members who had supported the reform described the funding as unfair and undemocratic. Opposition leader Tony Abbott sounded the death knell when he withdrew support. The government avoided holding the vote when Julia Gillard was deposed in a partyroom coup by Kevin Rudd. He moved the date for the federal election forward by one week which left no time for the referendum and the idea was dropped.

Albanese has made the right call in sticking the course and affirming the voice referendum will be held this year. Doing otherwise might have provoked a High Court challenge.

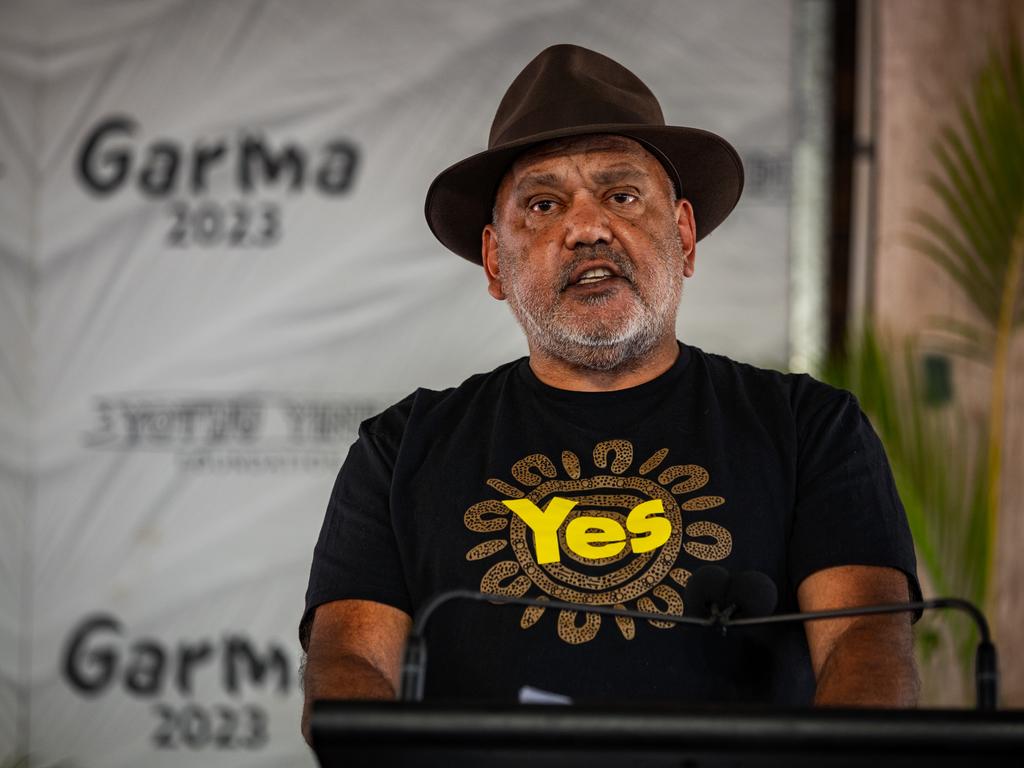

In any event, it would have been wrong to delay. It would signal weakness and indecision, and risk a loss of faith among the overwhelming number of Indigenous peoples who support the poll. It is telling that Indigenous leaders such as Noel Pearson have dismissed calls to delay the poll and instead rallied the troops by making it clear the referendum can be won.

Australia is on the right trajectory to hold the voice referendum in October this year. This gives supporters of the voice ample opportunity to convince the nation. They must grasp this now that Albanese has banished calls for delay and change.

The coming weeks will put the Yes case fully to the test. It must galvanise the nation if it is to achieve the first successful referendum since 1977 by having a majority of Australians and a majority of states vote for change.

George Williams is a deputy vice-chancellor and professor of Law at the University of NSW and co-author of Everything You Need to Know about the Voice (UNSW Press, 2023).

Many calls have been made to delay, modify or even cancel the voice referendum.