There are two foundation stones to the success with China of Anthony Albanese and Penny Wong – their bipartisan support for Scott Morrison’s strategic resilience as Beijing tried to break Australia’s will and Labor’s determination to transform the tone and atmospherics around the fractured relationship.

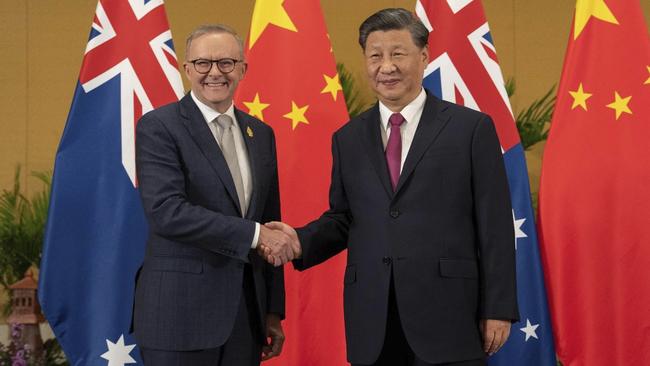

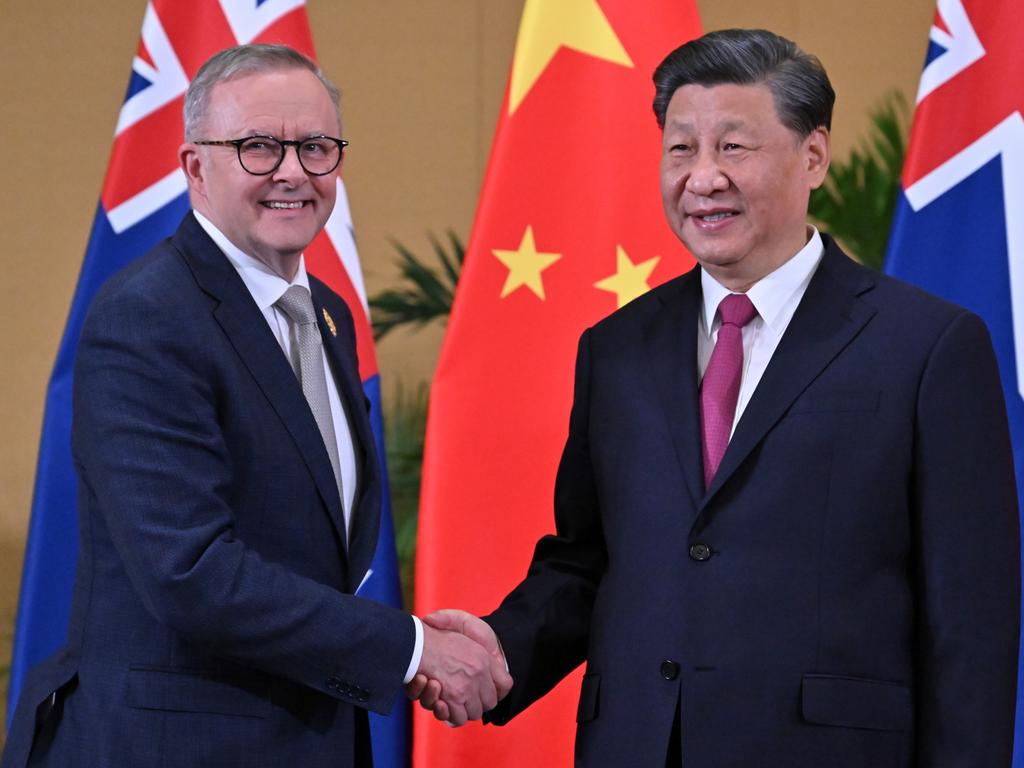

Both these Labor decisions, in opposition and in office, have been fundamental. The remarkable feature of the Albanese-Xi meeting is that the Labor government made no concessions to Beijing. The meeting reflects a reappraisal by China that is not confined to Australia, with President Xi Jinping moving to a more engaging diplomacy.

But Labor’s diplomacy has been vital. It is untenable to think this meeting would have occurred had Morrison won the election. The bad blood ran too deep. It is easy to forget the pessimism that marked relations during 2021 when it was assumed a change of government in Canberra was necessary for any improvement in ties.

How much Wong did behind the scenes is unknown. But it worked. After the bilateral there was no boasting from Albanese and Wong, no chest beating or self-praise, no talk about historic achievements. Their sustained discipline and focused diplomacy is a model. In part, that’s because they are realistic; in opposition and in office they displayed no illusions about China. How could it be otherwise given Beijing’s retaliation against this country?

Albanese and Wong have found the right formula – saying we will co-operate “where we can” and disagree “where we must”. Their message: Australia will assert its interests and values just as China will. The most pathetic response came from sections of the right-wing media, trying to belittle the meeting by saying it only went for 32 minutes and didn’t involve China ditching its trade sanctions.

What nonsense. Albanese was correct in saying the meeting itself was the success. It ended the deep freeze with no dialogue between an Australian PM and Xi since 2016 and Chinese ministers refusing to take phone calls in the previous term.

The meeting opens a new phase in relations. It is likely to be a more difficult challenge. Xi has sent the signal and, over time, China’s system will respond, a point made by Albanese. After the meeting he was optimistic about Beijing easing restrictions on trade but said “it will take a while to see improvements”. That’s prudent.

But expectations are high that Beijing will phase out its trade boycotts. The deeper reality, however, apart from the trade relationship, is that Labor has little scope to offer Beijing much in terms of political substance. And once the relationship is about issues of substance the question of Australian concessions comes into play.

This will test Albanese and Wong. They will want to shun any perception they are doing China’s bidding or accepting China’s framework for the region. The irony, however, is that China will have more leverage when dialogue is restored and relations are stabilised.

Its tactic of intimidation has failed. This became a decisive moment in Australian foreign policy and national resilience. Former Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade head Peter Varghese told me last year: “I think China is probably surprised that we didn’t give in, given the sheer extent of the retaliation.”

Morrison was consumed by a sense of mission – he felt China was trying to break the Australian government and break him as PM. He felt this personally and, too often, he reacted personally. Albanese’s response was illuminating. He believed China’s campaign must be resisted and he had a political interest in ensuring Morrison and Peter Dutton would not succeed in turning the issue against Labor.

In his March address to the Lowy Institute as opposition leader, Albanese reiterated Labor support for the 2020 Defence Strategic Update, for nuclear-powered submarines, for the Quad, for the Huawei ban and tough foreign interference laws. He said national security should “sustain maximum bipartisan consensus” and that it depended ultimately on “our unity as a country”.

It was Morrison, following Malcolm Turnbull, who engineered Australia’s realignment in seeking to counter China. But from this vantage, Labor’s bipartisanship assumes a long-run import. Labor has always been sensitive to Liberals playing the domestic China card against it, a constant theme in Wong’s speeches. Indeed, this was most memorably and dishonourably displayed in Billy McMahon’s attack on Gough Whitlam for his 1971 visit to China, branding Whitlam “a spokesman for those against whom (Australian soldiers) are fighting” in Vietnam.

Morrison and Dutton blundered with “Manchurian candidate” claims along with threat of war talk. But the bigger story is obvious – Australian bipartisanship in a strategic concord that told China this nation was not for turning, that it possessed more resilience than Beijing grasped and that it would find renewed strength in its alliance partnerships.

And what is happening today? Dutton as Opposition Leader said of the Albanese-Xi talks: “As I’ve said from day one, as an opposition we will support the government where they get it right, where it’s in our national interest to do so and when the Prime Minister is on the world stage, it’s important for us to provide that support. It’s good to see the meetings – the bilateral meetings and in particular with China … we want a normalised relationship. We want a good trading relationship but most of all we want peace in the region.”

This reminds, again, that our China policy is always more effective when bipartisan. Dutton, like Albanese, is explicit: the Liberals, like Labor, like President Biden, support the status quo on Taiwan. Under this government, there is no Labor-Liberal strategic difference over Taiwan. And that’s what matters.

It doesn’t mean there won’t be political competition, rhetorical differences and hyperbole, there’s always political competition. Beyond that, Dutton will attack Labor if Albanese offers policy concessions to Xi in this new phase of the relationship – and Labor knows that.

Wong’s elevation to Foreign Minister has been critical, given her energy and credibility contrasts with her predecessor, Marise Payne, who was unable to shape any public debate. The other contrast is Simon Birmingham’s elevation to shadow foreign minister – it is Birmingham who is now prominent in articulating Liberal China policy, unlike in the former government when, given Payne’s absence, Dutton as defence minister seized much of that role outside of the leadership.

Albanese and Wong are aware of the deep strategic differences and dangers between China and the US. They know any number of things beyond their control could go wrong – cyber attacks, security issues, foreign interference, new geo-strategic disruption.

There are three certainties: Australia’s dialogue with China will grow and that’s good; there is little prospect that Xi will modify his strategic rivalry with the West and that guarantees permanent uncertainty in bilateral relations, and; Beijing’s efforts to influence Australia will continue relentlessly, only the tactics will alter.

The cordial Albanese-Xi meeting is a breakthrough event driven by a reassessment from Beijing that offers new hopes for bilateral relations but is grounded in a strategic truth – that Australia’s steadfast resistance to China’s bullying and intimidation has left the country in a stronger position.