It’s a new dawn, but the Chinese dragon remains the same

Canberra is in danger of being seduced into thinking this is a new chapter. Like the forced re-education Beijing routinely inflicts at home, eventually, even recalcitrant prisoners are let go.

It is nonetheless being wildly misinterpreted by many of its friends and many of Albanese’s admirers.

It’s just as significant as they claim and reflects great credit on Albanese. But it’s not significant in the way they say.

Albanese’s meeting is more important than that between Gough Whitlam as opposition leader and Chinese premier Chou Enlai in 1971, or the Australian Great Helmsman’s even more famous meeting with Mao Zedong in 1973.

Geoff Raby, a former Australian ambassador to Beijing, leads the misinterpretation of the Albanese meeting. Raby is reliably pro-Beijing in most, not all, contexts. In his misinterpretation, the main problem in China relations was the unreasonableness of the Morrison government and all Australian governments over the past decade. The softer tone of the new Albanese government was thus all that was needed for benevolent Beijing to forgive us our sins.

Jennifer Westacott of the Business Council of Australia, normally an immensely sensible and thoughtful business leader, was seriously ill-advised to describe the meeting as “ a tremendous reset” of the relationship.

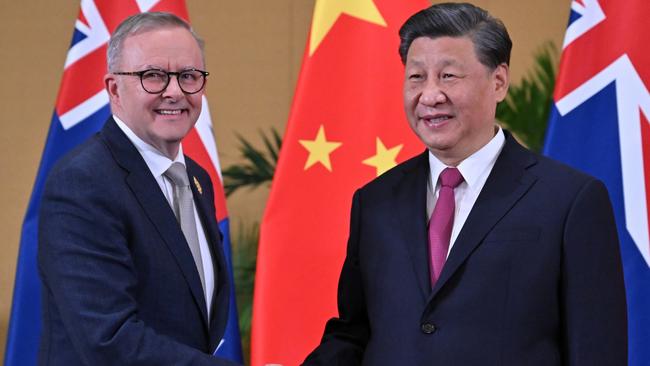

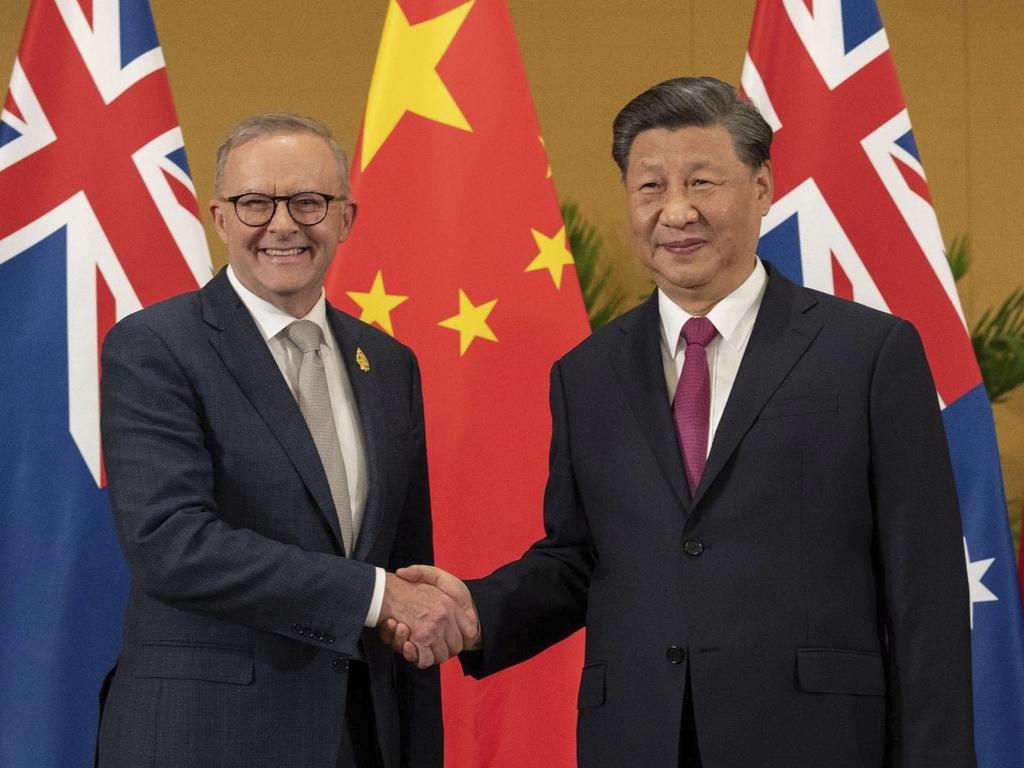

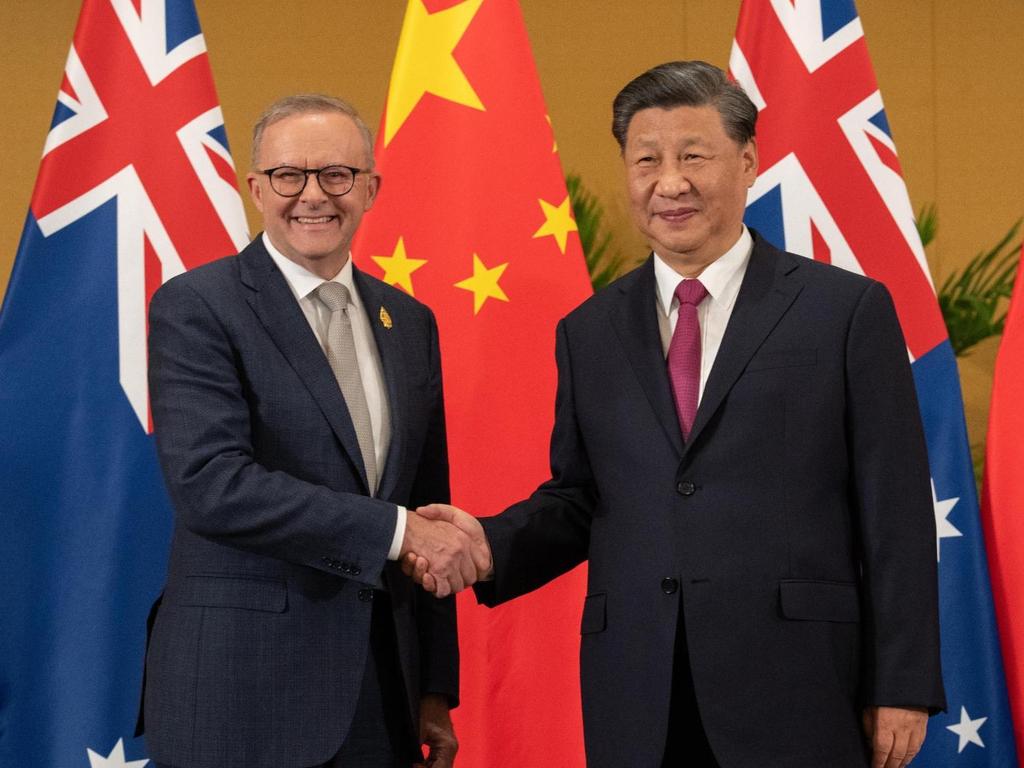

This was a week of momentous change and activity in geo-strategic issues, but let’s stay focused on the Albanese/Xi meeting. It’s wrong to see it in isolation, or even to imagine that Australian statecraft was primarily responsible for bringing it about.

Beijing has put a series of countries in the doghouse over the years, mainly for refusing to be dictated to by China. Such countries include Japan, South Korea, Germany, Britain, Lithuania oddly enough, Singapore, the Philippines and most recently Canada, as well as various others.

It does this to try to force them to change policies it doesn’t like. Inevitably, at some point Beijing decides it’s dished out enough punishment, or it’s having arguments with too many nations at once, or it wants something new from the doghouse resident, or it just gets bored. In any event, eventually it rehabilitates the offending nation.

It’s roughly analogous to the forced re-education routinely inflicted on prisoners in what Beijing euphemistically calls “residential detention”. Eventually, even recalcitrant prisoners are let go.

So why did Beijing make up with Canberra now? Its economy is doing relatively poorly and it’s facing pressure from US efforts to partly decouple from China, especially in hi-tech. The most striking example was Joe Biden’s executive order banning the export of semiconductor chips to China.

Further, it’s clear the wolf-warrior style of hyper aggressive diplomacy Beijing’s diplomats practised for several years was deeply counter-productive. It drove other countries to band together to hedge against Chinese aggression. Thus the Quad – the US, Japan, India and Australia – was revived first under Donald Trump, then more comprehensively under Biden. All Quad members plus South Korea and others are increasing their defence budgets. Wolf-warrior didn’t work.

Beijing wants to join the Trans Pacific Partnership. Individual TPP members can veto this. Albanese told me recently Canberra won’t even consider the question while Beijing has trade bans on Australia. Similarly, these bans have hurt China’s interests, forcing it to buy less calorific coal than Australia produces.

There are surely internal Chinese political dynamics about which we have no idea. It’s a very opaque system, even to Western intel agencies.

So why, if the impetus came from Beijing, do I rate the meeting a historic triumph for Albanese and his government?

First, the summit is just one episode in what is emerging as a sophisticated and integrated diplomatic and geo-strategic program from Canberra. This has been a dizzying six months of foreign affairs activism. Amid the blizzard of activity, three events are key: the Quad summit in Tokyo; the summit Albanese held with Japan’s Prime Minister, Fumio Kishida in Perth, and the Joint Security Declaration the two leaders signed; and now the meeting with Xi in Bali on the sidelines of the G20 summit.

On their first day in office, Albanese and his Foreign Minister, Penny Wong, flew to Tokyo for the Quad summit. This was a crucial statement of priority and resolve. In his meetings with Biden, and in his encounter with new British PM Rishi Sunak this week in Bali, Albanese underlined Labor’s commitment to the AUKUS agreement, under which Canberra will acquire nuclear-powered submarines.

More broadly, AUKUS is a military technology agreement. Albanese described AUKUS to Sunak as “central to Australia’s security”.

Then came the Joint Security Declaration with Kishida. This used the same language about the two nations consulting on adverse security developments and working out what to do in response as the ANZUS Treaty. This is pretty much standard language for US security treaties in Asia. It’s much the same language as is used in the US-Philippines security treaty.

When the Japanese cabinet met before the Perth summit to approve the Joint Security Declaration, they made a historic determination – that Australia was Japan’s second most important security partner after the US. Japan’s ambassador in Canberra, the influential Shingo Yamagami, has described Australia in these terms. He also said Australia and Japan were in an alliance in everything but name. This is not freelancing from Yamagami, who comes from the heart of Japanese foreign policy. This is Tokyo’s strategic view.

The Quad, AUKUS, and the Japanese Joint Security Declaration are good in themselves and well considered. Beijing despises them, absolutely despises them. They contradict in spirit and substance, in letter and intent, every element of contemporary Chinese strategic policy. Beijing has denounced all three. That is what makes Albanese’s achievement so historic and singular.

Now, recall that just a couple of years ago the Chinese embassy was demanding Australia satisfy 14 of Beijing’s “grievances”.

In the early days of the Albanese government, China’s ambassador, Xiao Qian, demanded Canberra take “concrete action” to improve the relationship.

The Morrison government got much more right than wrong in its dealings with Beijing, and in foreign policy generally. It stood up to Chinese aggression. It made three mistakes, however. In its later months it routinely talked about possible war with China. That’s irresponsible. Secondly, while it negotiated the important AUKUS agreement for long-term benefit, it did nothing to increase military capability over the next five to 10 years, so it lacked credibility. It also led a public call for a full investigation into the origins of Covid. This was justified in theory but achieved nothing.

The Albanese government has dropped the war talk and generally dialled back the rhetoric. It has settled on a good formula, used by Albanese, Wong and Defence Minister Richard Marles: it seeks to stabilise the relationship, it will co-operate with Beijing when it can, disagree when it must and not resile from Australia’s interests or values.

At the same time, it has reiterated repeatedly that it is sticking by the US alliance, the Japan security relationship, the Quad and AUKUS, and for good measure intends to significantly boost Australia’s defence capabilities over the next five years, to make us, as Marles says, a strategic porcupine, very dangerous to get mixed up with.

Thus, the Albanese government has given away absolutely nothing to Beijing. Indeed, it has continued on policy paths which Beijing hates. It has added new policies which Beijing also hates – such as the Security Declaration with Japan and the promise of increased military capability. Yet it’s seen relations with China restored to functional normality. That’s the real significance of the Xi/Albanese summit. That’s why it’s historic. It’s an example supremely of Australia holding its strategic nerve across both sides of politics and several electoral cycles.

This is a judgment shared by strategic hardheads in Washington, Tokyo, New Delhi, Seoul, London and other capitals concerned with China.

Just imagine if Albanese had rejected the Quad, which Labor opposed under Kevin Rudd; or rejected AUKUS, which Labor elder statesman Paul Keating denigrates and demonises with a passion only equalled in Beijing.

In that case, Beijing would have seen nothing but weakness, our friends would be dismayed, and it’s unlikely Albanese would have had the universal access he got to world leaders in Cambodia and Bali. Only the baying pro-Beijing brigades would have lauded him. And Australia would be immeasurably weaker.

For a guide to Canberra’s strategic standing, take Mike Green, CEO of the US Studies Centre at Sydney University. Green is the pre-eminent American authority on Asian strategic policy. He was the Asia director in George W. Bush’s National Security Council, and is the author of definitive books on Asian geo-strategic policy.

I have known him for many years. He is hard-headed and weighs his words carefully. Here is his crucial judgment: “I cannot think of an Australian government that has had a stronger series of successes at the outset. This comes in part from strategic continuity. The new government did not fundamentally change the strategic pillars of Australian policy. This was very reassuring to Australia’s partners.”

The Albanese government did change some things – not only the tone towards Beijing but also its activism towards the South Pacific and Southeast Asia. Wong has already visited 21 countries, mostly in the Pacific and Asia.

It also changed climate policy. I think its policy there is excessive, but it’s certainly popular in the South Pacific, with the Biden administration and in Europe.

The government must also bring its base along. This is always a challenge for Labor. The new government stands in the tradition of Bob Hawke, Kim Beazley and Gareth Evans, who managed the US alliance and regional diplomacy very effectively, infinitely better than Gough Whitlam did.

Wong’s recent Whitlam Oration was a masterpiece in leading Labor true believers to sensible policy. Rather daringly, she placed her government’s hard-headed attitude towards Beijing today within the framework of Whitlam’s embrace of China in the early 1970s.

Her key sentences were: “The China of today is not the same as the China of the 1970s or even the 2000s … It is an insult to all Gough did … if we act as though we live in a world that has long since passed.”

She outlined the key feature of the present environment: “The structural differences between Australia and China – different values and different interests. As China has sought to assert itself in the world, those differences have become harder to manage.”

Wong’s address was not a balanced assessment of Whitlam’s foreign policy. She left out, among other things, Whitlam’s attempt to secure election funding for the ALP from Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi Ba’ath Socialist Party; Whitlam’s hatred of Vietnamese refugees and his several statements to that effect, including when he told his foreign minister Don Willesee: “I’m not having those f..ing Vietnamese Balts coming into the country with their religious and political prejudices against us”; the fact that not only the US but Britain and Canada also cut back intelligence sharing with Australia after Lionel Murphy’s bizarre ASIO raid; Whitlam’s recognition of Soviet sovereignty of the Baltic states; his government’s prohibition on ASIO eavesdropping on East European embassies with all their spies; Lee Kuan Yew’s withering assessment in his memoirs of Whitlam as an arrogant sham, and much else in similar vein.

But her purpose was not a balanced assessment. It was, in an age-old ALP governing manoeuvre, to turn a Labor legend, no matter how ropey, to the service of good contemporary policy.

Whitlam’s embrace of China is wildly overstated in its significance and has been almost universally damaging in Australian policy. Whitlam sold out Taiwan much more comprehensively than he needed to, and subsequently refused to take many elements of Chinese policy seriously, such as Beijing’s sponsoring of deadly communist insurgencies against our friends throughout Southeast Asia.

Most importantly, by idealising and romanticising our relationship with a ruthless communist dictatorship, the Whitlam legend set up a hitherto destructive dynamic within Labor that considered any Canberra disagreement with Beijing to be a sign of failed Australian policy.

As political framing, Wong’s address, repudiating that dynamic, was brilliant.

Albanese’s government has been strategically steadfast and displayed real urgency when needed. It must now avoid a new danger, which is to be seduced into misinterpreting Xi’s honey words as if they mean a new chapter in relations with China.

All the strategic conflicts with Beijing continue. Just last week, Xi told his military to prepare for war. What he says at home is more important than what he says to us. It’s good to stabilise day-to-day relations. But the underlying realities, the contradictions and conflicts, remain intractable and dangerous.

Anthony Albanese’s meeting with Xi Jinping at the G20 summit in Bali, the first between Australian and Chinese leaders in six years, will burn itself into the history books.