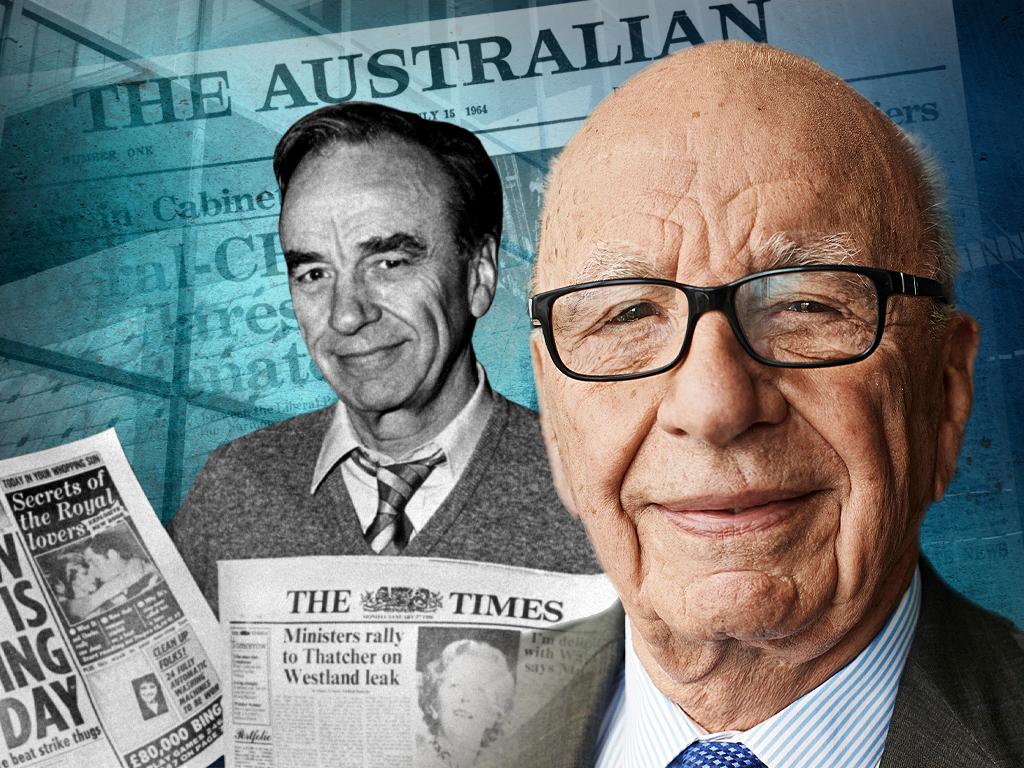

How Rupert Murdoch changed the face of media across the globe

These rules have been the pillars of his life and the basis of his success in shaping and dominating global media.

The legend of Murdoch has been built on his innate curiosity, ranging from technical innovation to an ear for gossip, his acuity in reading the tea leaves of society, his business flair and his gambler’s willingness to bet on new ventures.

During his seven decades at the helm of News Corporation everything has changed. And changed again. The only constant between 1954 and 2023 is Murdoch.

He has changed the face of media across the globe. He has weathered two print revolutions and is facing a third. He has introduced new ways of consuming media, such as subscription television, and has announced he is stepping down as executive chairman of Fox Corporation and News Corp while in the centre of far-reaching jockeying to define a news media future within the world of artificial intelligence.

The first major revolution in newspaper production came in incremental moves through the ’70s when computers and photo typesetting rendered hot metal obsolete. Locally, the move to the new technologies was slow, costly and contested by unions.

In the UK, where Murdoch owned The Sun, the News of the World, The Times and the Sunday Times, there was no movement. Fleet Street was in the iron grip of unions, overmanning and featherbedding was rife and innovation verboten. This convinced Murdoch the only way ahead was to crash through using new technology in an all-new state of the art computerised production facility.

This was Wapping, the 1986 year-long arm wrestle with the unions that Murdoch won, allowing the entire British newspaper industry to follow and prosper. The great profits that flowed from Wapping underwrote the next chapters of his achievements.

The launch of Sky satellite TV in the UK in 1989 was another bet-the-company moment, but after a faltering start and a few missed heartbeats, it created the subscription TV template that soon spun off multi millions in profit.

Many pundits confidently predicted Murdoch had overstepped with his moves into TV. But they forgot he had launched NSW 9 in Adelaide in 1959 and had run with flair and vigour the Channel 10 network in Australia through the ’80s, until cross-ownership provisions of media regulations forced him to sell when he acquired the Herald and Weekly Times business in 1987.

He was therefore no stranger to TV when he began acquiring US TV stations to form the Fox network in the mid ’80s – a move experts predicted would fail because of the might of the incumbent free-to-air networks.

A decade later he took the great gamble that led to Fox News. Murdoch’s hunches and his company’s research revealed an untapped media market within the US – the masses of people who felt alienated by what they saw as left-leaning American mainstream media.

It was big, bold and brassy, and it clicked with millions of viewers.

When the balance sheet of Murdoch’s life is being written, Fox News will figure strongly because alongside its billion-dollar a year financial success came fearsome controversy about its proclaimed harmful effects on American, and global, democracies.

Those who oppose or complain about Murdoch put the blame for current division within America firmly at his door. But what they’re really complaining about is that he, an outsider they saw as a buccaneer, stole their lunch by seeing the market opening, aiming his output at the masses of disaffected citizens, and showed up his competitors as lazy and afraid to innovate.

During the last two decades of the 20th century News Corp’s growth was exponential.

Murdoch, keenly aware that in the emerging digital age that content would be king, added the Twentieth Century Fox film studios to his bag of assets and bankrolled the highest grossing movie to this day – Avatar.

Not every move worked. He bought TV Guide in the US for $US3bn just as free-to-air TV was losing its grip on audiences to cable services, and he paid over the odds for the early internet darling MySpace, only to see it quickly overrun by Facebook. The advent of the digital age was the second revolution in media that challenged every player, but it was Murdoch who had the courage to overturn early giveaway policies and impose subscription gates on his newspapers. The publishing world followed.

We are now on the brink of yet another digital-inspired revolution. The rise of artificial intelligence will shatter current templates and present huge new challenges.

It will fall to Murdoch’s elder son, Lachlan, to steer News Corp into the AI world where digital giants led by Google and Facebook hoover up vast amounts of information from myriad sources and conflate it into seemingly credible stories. But AI is not always accurate, reflecting the first rule of computers – garbage in, garbage out. AI makes fraud and fakery almost indistinguishable from fact.

The further threat is that the digital giants sweep information sources that are costly to establish and sustain – such as newspapers or TV networks – and gobble up information without payment.

How this will be sorted is anybody’s guess, but Lachlan will have an advantage courtesy of his father’s pioneering deals with Google and Facebook to pay for information taken from News Corp and re-used for their own benefit.

Rupert Murdoch’s lifework has been driven by a philosophy of free speech and free thought.

The new challenge will be how to uphold those values in an AI world where the very essence of truth is contested.

When I was a cadet reporter at The News, Adelaide, in the early 1960s Rupert Murdoch demanded of us that we question everything, write for the masses rather than toffs, be entertaining – that is, not boring – and never be afraid.