Inside the battle of Wapping and the future of newspapers

London’s print unions had paralysed newspapers and were happy for them to die off. Rupert Murdoch was not.

The standover tactics of the London print unions was a 399-year-long racket born in 1587, when the Worshipful Company of Stationers agreed that just 1250 copies of any book would be printed from a set of lead type.

After that, another set of type needed to be made, letter by letter, line by line. Not because the lead type had worn out, just so the printers could charge for the work.

At least it was work. By 1980, when I arrived as a sub-editor at The Times, these standover tactics were managed by two unions: the Society of Graphical and Allied Trades and the dominant National Graphical Association which, between them, boasted more than 335,000 members.

They had a stranglehold on newspaper publishing and decided who would be employed and even what they would be paid.

I was intrigued about a fellow who sat in an office fashioned beneath a stairwell. He always had a copy of that day’s newspaper before him, a printer’s line gauge and a note pad. I was told he was measuring “the fat”. It is hard to believe now – it was hard to believe then – that this man was paid to add up the columns of the advertisements that had not been set by the in-house unionists and then issue the company a bill for them as if they had. All this while surrounded by hot-metal printing processes that would have been familiar to the Johannes Gutenberg who had invented the printing press in 1440.

This tyranny included compositors refusing to typeset stories with which they disagreed. Newspaper libraries hold these editions with odd white spaces on pages that sit like black marks on the masthead’s soul.

All this rendered most Fleet Street newspapers unprofitable. When the owners of Times Newspapers sought to introduce “new technology” – phototypesetting had been around since 1949 – its titles were shut for 50 weeks. Union workers didn’t miss a beat – nor a pay packet.

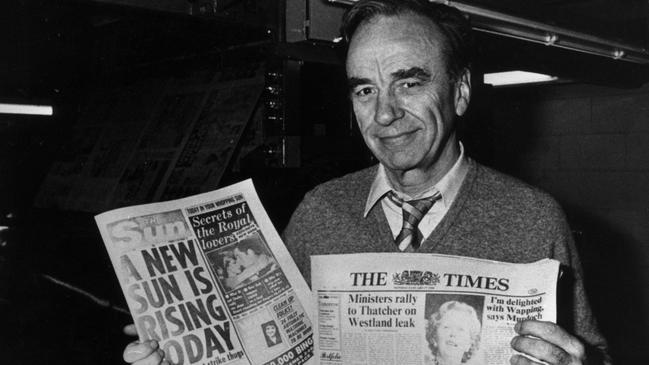

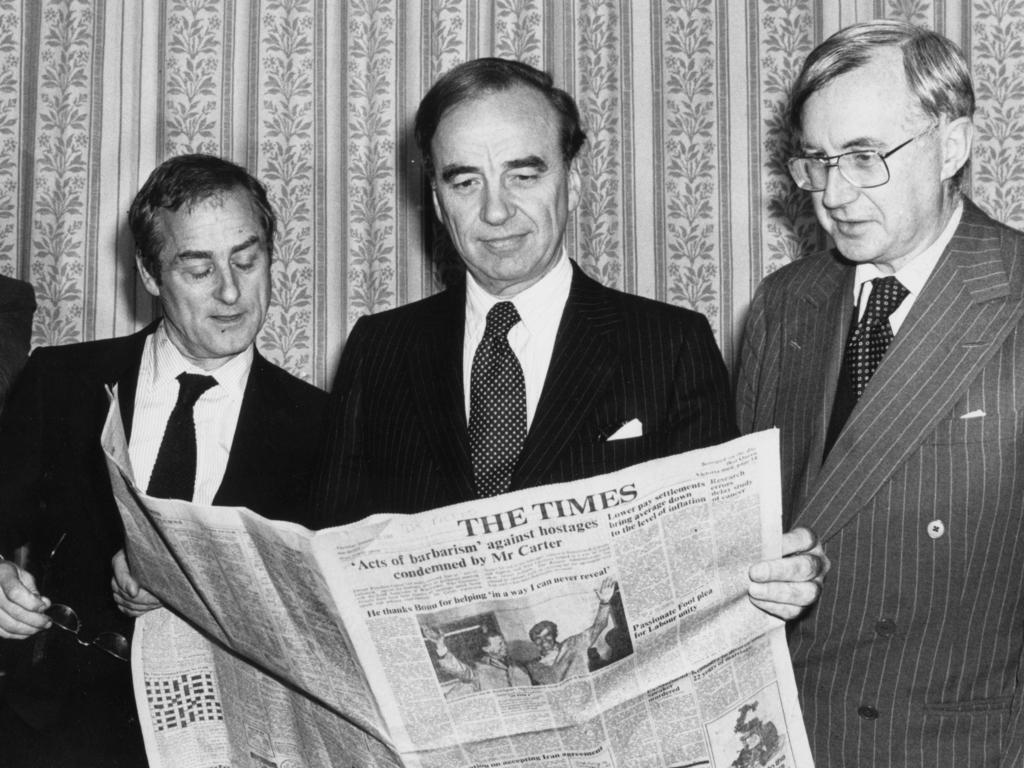

Frustrated, the Thomson family sold the legendary mastheads. The buyer was Rupert Murdoch. At first, there was no change; the print unions would start the presses and seek negotiation on one issue or another. Murdoch’s rule was firm: no negotiations while the presses were running. Either the newspaper was printed or it was not. And sometimes we lost an edition.

By then almost every News Corp newspaper had switched to computer technology. Job losses were unavoidable, but commonly negotiated in good faith. There would be none of that in London with the unbeaten NGA and SOGAT.

And so began a fight between the future and the past. When these two wrestle, the old world always loses. It’s why we fly overseas rather than spend weeks on a liner, and why we no longer hear the nightmen with their whiffy consignment.

London’s print unions had paralysed newspapers and were happy for them to die off. Murdoch was not. He built a new printing plant in Wapping just west of Tower Bridge and invited the unions to join in the future of his newspapers, but it would not be a closed shop.

They couldn’t agree and others – considerably fewer of them – filled their places.

Timid rivals, The Guardian and Mirror Group Newspapers boss Robert Maxwell, jeered from the sidelines as Murdoch won a war they had not the heart to contemplate. “It’s not the British way,” sneered Maxwell, who would steal $1.5bn from his employees’ super scheme.

Unshackled from print union despotism other newspapers sprang to life: The Independent, The European, The Sunday Correspondent. Jobs were created. The barriers to entry of this business were lowered and others could take part. And perhaps make a profit.

On that celebrated night of freedom – Australia Day 1986 – we put together the first edition of The Times and, despite the thousands of picketers rioting at the gates, it circulated around Britain.

Murdoch came up to me when the edition was “off the stone”. “Bloody exciting, ain’t it?”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout