Why we will likely never fully understand dark matter - but we can try

Because dark matter doesn’t emit, reflect or absorb light, it is invisible. This exhibition takes a surprising approach to illustrating the ‘stuff’ that is said to make up 95 per cent of the universe.

Most of us probably assume that the material world is, if not the whole of reality, at least the easiest part of it to understand. It’s composed of visible and tangible things that can be quantified in various ways and whose behaviour can be expressed as the laws of physics, mechanics, optics, etc. This is the world studied by science and exploited by industry and technology; the spread of this new form of knowledge from early modern Europe to transform the lives of all of humanity is the most important development in the past five centuries of human history.

But matter itself has never been easy to define. This was the original question asked by the early Greek thinkers who, in the 6th century BC, established the basis for philosophical and scientific thinking. Thales was the first to suggest that all things that exist are made of some common underlying substance that is capable of taking different specific shapes or reverting, in entropy, to its primal form. He suggested water, because although inherently liquid, it can also freeze and evaporate. Others suggested air, or an indeterminate primary substance without specific characteristics.

There was, however, no word for matter. There were no words for any of the abstract ideas these first philosophers – heroic explorers of the mind, as Nietzsche recognised – were groping their way towards. They had to make do with words for everyday phenomena, which they extended and used figuratively, eventually creating what became two centuries later, by Aristotle’s time, a whole technical vocabulary of philosophy. What we know of these very first thinkers is largely paraphrased by Aristotle and other later authors, although a few formulations and expressions probably represent the terms they actually used.

Some years ago, I was struck by a passage in Caesar, where he mentions that the houses in Alexandria – where he was being besieged by an evil eunuch, but that is another story – are not prone to fire, since they are not made of “materia”. But the primary meaning of this word in Latin is “timber” or “stuff from which something is made”. It was extended to the metaphysical concept of “matter” by Caesar’s contemporary Cicero, in imitation of the Greek “hyle”, also meaning timber, wood or forest, which had been adopted by Aristotle to name the substance (“substance” means that which stands under) of which physical reality is composed, and which can take different forms.

Even though Aristotle developed clear ideas of matter, form and three kinds of soul, his concept of the four categories of causality left open the sense that even “inanimate” matter was not wholly without a sense of innate purpose or teleology. It was only in the early modern period that an idea of radically inanimate matter was developed; this was useful for the pragmatic ends of modern science, but led to the philosophical problem of dualism.

Since that time, however, the concept of matter has grown more complicated again. Over the past century and a half our understanding of the structure of the atom has grown enormously, in the process calling into question many earlier assumptions about the stability both of our theories of matter, and of the relation between matter and energy. Three hundred years ago, Alexander Pope could say:

Nature, and nature’s laws lay hid in night;

God said, “Let Newton be!” and all was light.

Today, however, as the title of this exhibition suggests, we are much less certain that all is light. On the contrary, although we possess vastly more powerful instruments for studying both the cosmos and matter itself, we seem to be less confident than ever of understanding the ultimate nature of being. And that is one of the reasons that it is interesting to involve art with science that is itself working on a speculative frontier of research.

The exhibition comes from CERN, which is based in Geneva and represents 23 member states and operates the largest particle physics laboratory in the world. It has also had an arts program for more than a decade; this is a natural partner for the international Science Gallery Network which was begun by Trinity College in Dublin in 2008, and now has seven galleries around the world, including the new Science Gallery at the University of Melbourne, officially opened in 2022 although I reviewed an earlier exhibition in temporary premises (Perfection in September 2018).

The premise for the present exhibition is that the world of matter is even more complex and obscure than we had previously realised: Monica Bello, Head of Arts at CERN and co-curator of Dark Matters writes: “We don’t know what makes up 95 per cent of our universe – which we believe is both dark energy and dark matter. But because dark matter doesn’t emit, reflect or absorb light, we cannot see it or touch it. It continues to be elusive as we continue our ultimate quest to understand it.”

As already suggested, most of us would identify the material world with the things that we can see and touch all around us. Of course we know that even the visible world is not as simple as we pragmatically assume; things are only visible to us because light is reflected from them and because we have evolved organs of sight that translate that reflected light into what the visual cortex imagines as objects in space and distinct colours.

But what of an invisible world? How can we even know that such a world exists if we cannot see or touch it? The answer is that we infer or hypothesise its existence from gravitational phenomena or from the gravitational forces that must be present to account for the cosmos we know, but which cannot be explained by the mass of the matter we can actually see.

In the mid-17th century, the great French thinker Blaise Pascal reflected on the new worlds that had been opened to our view by the invention of the telescope and the microscope and imagined man as being lost between “ces deux abîmes de l’infini et du néant”, these two abysses of infinity and nothingness. But that was just the visible infinite; now we are told that the whole cosmos that has inspired awe and even existential terror for centuries represents just 5 per cent of the matter we believe to exist.

One would think that even the slightest awareness of these abysses of the unknowable would put our own brief lives into a radical perspective, and help at least to free us from some of the illusions that constrain our existences and harm those of others: prejudice, bigotry, miserable attachment to ethnic and tribal identities, the self-constructed mental prisons of ideologies, the contagion of mob outrage. But humans are wedded to these expressions of the ego precisely because they blind us to the reality of nothingness.

We don’t even really know where this world came from. When we are told that scientists have modelled what the universe was like some tiny fraction of a second after the Big Bang, that still doesn’t answer the question of what it was like before, or where its materials came from. This ends up being hardly more satisfactory than being told that God created the world from nothing.

And it leaves us wondering whether we are not still struggling with the perception of a reality which, as Kant said, the human mind can constitutionally only understand in the dimensions of time and space. What if time and space do not actually exist beyond the human mind? One of the scientists quoted in the exhibition points out that water flowing from a tap only appears thus to us at a certain velocity; if we took photos every nanosecond, all continuity would disappear.

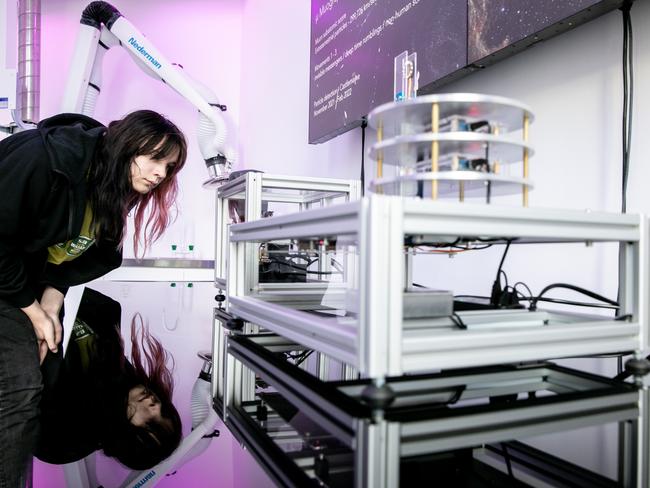

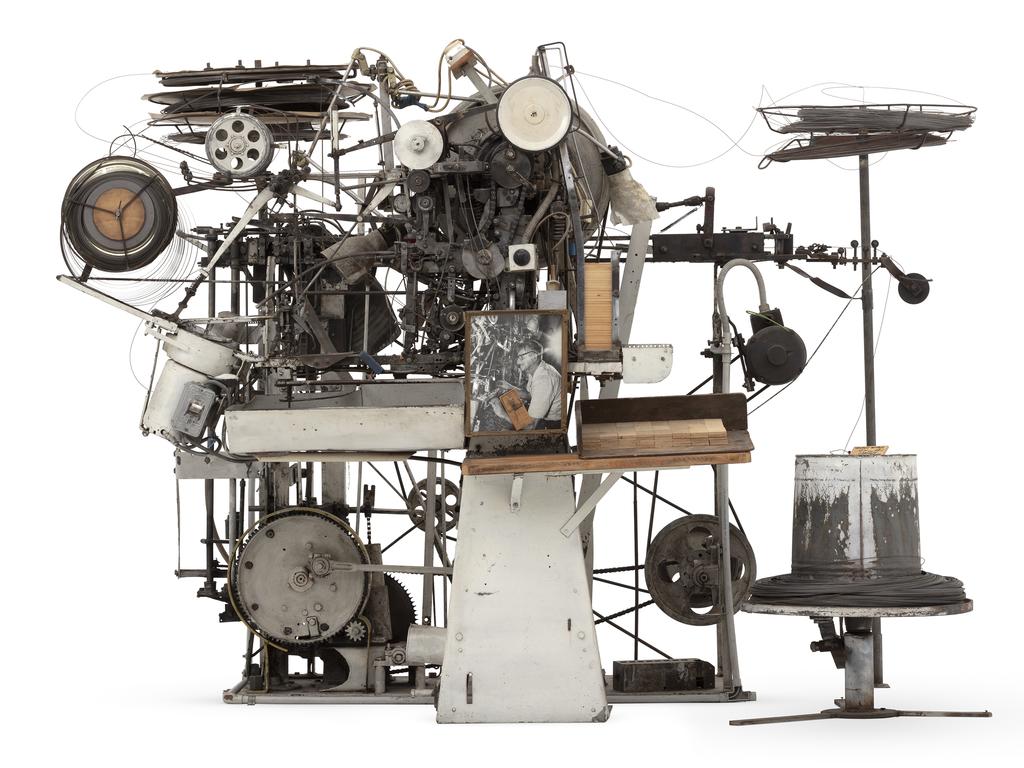

Within the exhibition, several of the most suggestive works attempt to make aspects of the invisible world visible and even tangible to us, including the quivering and luminous curtain through which we enter the exhibition and another work that has spun jumpers of copper wire, set on replicas of parts of the Large Hadron Collider. Others play on the way our imagination interprets things not actually seen.

One of the most interesting pieces is based on a device for detecting the subatomic particles known as muons. These can’t be directly seen, but they are picked up in different ways by two devices here. The first pings regularly as it registers a cosmic radiation strike, but every few minutes it gets a double hit, which apparently signifies a muon strike. When I first looked, the two cosmic ray detectors each had almost one million hits, but just 22,056 muons had been detected. By the time I left, this count had gone up to 22,067, and I twice witnessed a little ring of lights flashing to register a muon.

The other device uses materials called scintillators, which emit light when they are struck by a muon, and these strikes are registered as marks on a monitor screen. The complete set of muon traces from a previous presentation of this work is visible on another screen, and this was used, with a music synthesiser program, to create the musical score that is played in this section of the exhibition.

Of course one cannot help thinking of the ancient doctrine of the music of the spheres, in which the crystalline spheres of the planets made music as they orbited one within the other. As Lorenzo says in The Merchant of Venice (Act V, sc. 1),

There’s not the smallest orb which thou behold’st

But in his motions like an angel sings …

But this was before the new dimensions of reality revealed by the telescope and the microscope; the universe was vast and majestic, but finite. For Pascal, the infinite cosmos no longer produces music but has fallen grimly mute: “the eternal silence of these infinite spaces frightens me”.

Of all the works in this exhibition perhaps the most successful as art, in the sense of integrating scientific concepts with imaginative realisation, is a video on three screens incorporating a vocal soundtrack that could almost serve as a meditation app. The images include landscapes, the silhouettes of trees, city buildings and an old ruined stone house; but the images are digitally treated in a way that emulates a solarised photograph, that is where the image comes to resemble a negative, with shadowy outlines of light against a deep black background.

Thus while the text, printed as subtitles on the screen, reminds us that dark matter is something like the invisible backbone of our universe, the force that holds everything in place instead of allowing it to fly off in all directions, the imagery, too, presents a vision of enveloping and embracing darkness from which being emerges as spidery traces like a fragile tissue of metaphysical lace stretched across the void.

Dark Matters, Melbourne Science Gallery, until December 2.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout