How a handbag thief became Sydney’s most celebrated artist

Nineteenth-century artist Charles Rodius was transported to the colony after stealing a ladies handbag and went on to paint the leading citizens of Sydney.

By 1829, when Charles Rodius arrived in NSW, Sydney was just over 40 years old but already a rapidly growing city. The State Library of NSW, which is presenting the first monographic exhibition of this remarkable and little-known figure, had been established in its original form in 1826 and the Australian Museum in 1827. The Sydney Free Grammar School, the precursor of Sydney Grammar School, had opened in 1825 under the colourful Laurence Halloran, originally transported to the colony for murder but by all accounts, and in the estimation of Governor Lachlan Macquarie, a pedagogue of exceptional talent. Francis Greenway, a fine architect transported for forgery, had designed the Hyde Park Barracks (1819) and St James’ Church (1824) among other notable works.

Another important colonial artist had just left Sydney in 1828: Augustus Earle, who had arrived in 1825 and painted several portraits of colonial figures such as captain John Piper, Mrs Piper and their children (c. 1826) and governor Thomas Brisbane (1825), as well as landscapes and early images of Aboriginal people, including a full-length portrait of Bungaree, who had accompanied Matthew Flinders on the Investigator’s circumnavigation of the continent in 1801-03.

Unlike Earle, who was a free artist and subsequently joined Charles Darwin’s voyage on the Beagle (1831-32), Rodius arrived in Sydney as a convict. But his background was very different from that of most of the men and women transported to NSW. He was born in 1802 in the great mercantile city and trading port of Hamburg, then – long before the unification of Germany in 1870 – an independent city-state and former free city of the Holy Roman Empire. His family belonged to Hamburg’s large Jewish population, and his birth name was Joseph Meyer. The family may have been Christian converts, since the artist was later buried as a Catholic, according to the Australian Dictionary of Biography. But the same source also gives his birthplace as Cologne, a Catholic city, under French occupation in 1802 (1794-1814), so he could have been born a French citizen; or perhaps Rodius simply was trying to conceal his Jewish origins.

The young Meyer went to Paris to study art and presumably architecture, or architectural drafting, during the years of the Bourbon Restoration that followed the fall of Napoleon in 1815. He learned drawing, watercolour and the new printmaking technique of lithography but seems never to have studied oil painting. He settled in London in 1827, and at some point in this period changed his conspicuously Jewish name to Charles Rodius, with a Christian first name and a Latinate surname that recalls the forms adopted by Renaissance scholars, especially in the northern countries. Soon after his arrival in Australia, incidentally, the Sydney Herald published his new surname in Hellenised form: Rhodius, as though from the island.

Being trilingual and a gifted artist, the still very young man – only in his mid-20s – tried to earn a living in London teaching French, German and drawing but seems to have found it hard to make ends meet, perhaps because he had sophisticated tastes; he was fond of the opera, which he attended not long after Thomas De Quincey, who used opium to enhance his experience of the music, as he relates in Confessions of an English Opium Eater (1821). Rodius, though, appears to have taken the opportunity to steal women’s handbags, and it was for this that he was transported to Sydney. Fortunately for Rodius, as for Halloran and Greenway, the colony was in need of talented men and he was at once put to work in the Government Architect’s office, carrying out a survey of important buildings in Sydney and NSW. His abilities were more broadly recognised among the leading families in the city, too, and with their support he was granted a ticket of exemption in 1832, followed by a ticket of leave in 1834.

Much more will soon be known about Rodius as a result of the work of distinguished art historian David Hansen, curator of this exhibition, whose research in the extensive holdings of the State Library was supported by a Ross Steele fellowship, and we can look forward to the publication of Hansen’s book on the artist in the next year or two.

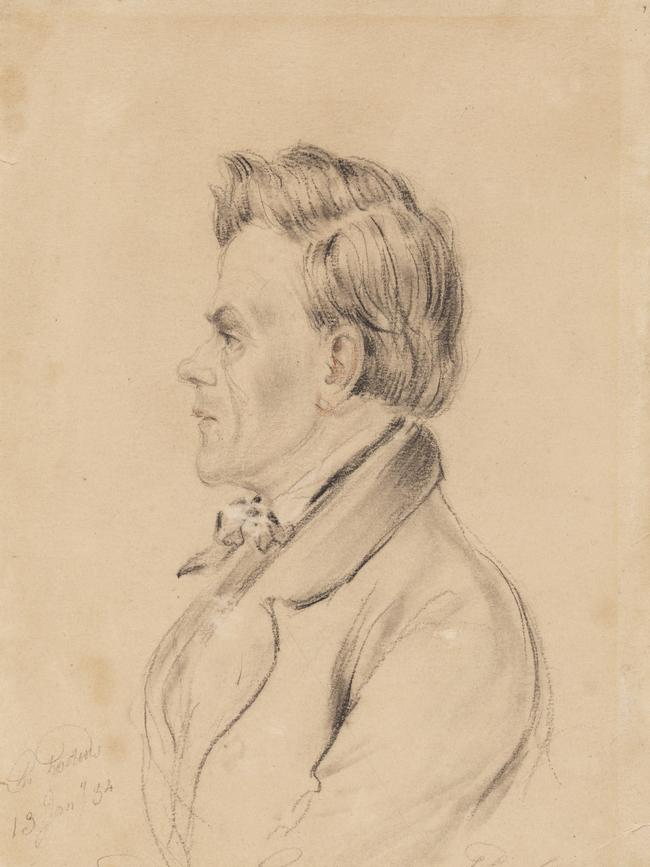

Rodius’s drawings have preserved vivid and sensitive likenesses of many of the leading individuals in Sydney almost two centuries ago – in some cases the ancestors of people we may still know today.

There is, for example, a striking likeness of the young Henry Parkes, long before he became the elder statesman with the beard of an Old Testament patriarch: clean-shaven and lean, he is drawn in court while prosecuting some employees for an illegal strike. Or Charles Windeyer, journalist, magistrate, politician and founder of a well-known legal dynasty; the reproduction of his portrait as a lithograph is evidence of his popularity and of a public demand for his likeness.

A few portraits stand out not only for their sensitivity and perceptiveness but also for a particularly high degree of finish, in contrast to the majority in which head and shoulders float on the white page; these are presentation pieces that, in their way, emulate the pictorial density of painting. Notable among these is the portrait of chief justice Francis Forbes, who had arrived in Sydney in 1824 and introduced the practice of trial by jury in the former penal colony. Forbes was also a supporter of Halloran, and later chairman of trustees at Sydney College (1830-50), the second forerunner of Sydney Grammar School, where Rodius was appointed master of drawing. He also subsequently became superintendent of drawing at the Mechanics’ School of Arts, the predecessor of the National Art School. The exhibition includes a self-portrait from around 1849, where he appears as an elegant and urbane gentleman – youthful for the age of 47 – whom we know to have been appreciated for his fine voice almost as much as his artistic talent.

The case of Windeyer shows that portraits could be both privately commissioned by the great and the good and published as lithographs for sale. Many of Rodius’s lithographic portraits, however, seem to have been of well-known public characters in the colony or of notorious villains whose features were an object of curiosity and perhaps horrified fascination, especially in an age that was intrigued by physiognomy, phrenology and other attempts to define the physiological basis of character. Thus the double portrait of murderer John Jenkins (1834) captures the impulsive brutality of a young thug, while that of John Knatchbull (1844) suggests the weakness and moral emptiness of the psychopath.

The features of both admirable and despised members of the community would very soon be recorded and disseminated by another technology. But the first daguerreotype was taken around 1837 – the same year as the beginning of Queen Victoria’s reign – and Rodius’s work belongs essentially to the last pre-photographic generation. He was aware, however, of the rising threat of photography and, according to the Design and Art Australia Online database, “he advertised in 1855 that he guaranteed ‘a correct likeness … at the same expense as a Daguerreotype or Photograph … and avoiding the stiffness which detracts so much from correct expression in the latter’.”

Rodius’s portraits are of an age before there was any easy mechanical alternative to preserving a likeness, and when, more generally, drawing was still considered a skill almost as fundamental as writing itself. It was not only the foundation of fine art but an everyday necessity to scientists, doctors, engineers, architects, soldiers and sailors. And, like writing, it was understood as a skill that everyone could learn to a reasonable and functional degree, even if most people are no more likely to become great draughtsmen than masters of prose style.

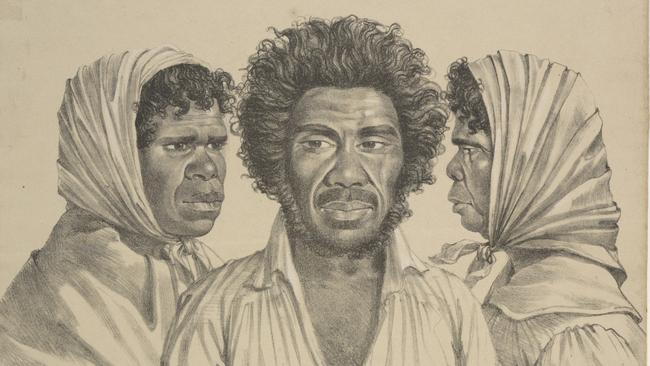

Just as memorable as Rodius’s portraits of the leading citizens of Sydney are his drawings and prints of Aboriginal men and women whom he may have met in the Domain and Woolloomooloo areas where they tended to congregate.

He was clearly interested in the subject from the beginning, for he drew a portrait of Bungaree in 1830, soon after his own arrival in December 1829 and not long before his sitter’s death in November 1830. Bungaree is wearing the same bicorn hat that he raises in salutation in Earle’s 1826 painting, but was in reality already unwell by this time. The Sydney Monitor reported in March 1830: “Mr C. Rhodius uses the lithographic press with great skill. He has executed front and profile likenesses of Bungaree, in a most superior style.”

There are many other Aboriginal portraits from the following years, and one of the great virtues of this exhibition is to bring together the State Library collection and some other works in private hands, with an important corpus of drawings and prints from the British Museum. Together, they bear witness to the closeness of the artist’s study of these sitters, many of whom can be seen in several versions, or compared in sketches and lithographic prints.

What most strikes us about these Aboriginal portraits, however, is a kind of honesty, lucidity and directness. Earle’s images of Aboriginal people, from his portrait of Bungaree to his lithograph Natives of NSW as seen in the streets of Sydney (1830), or landscapes like Waterfall in Australia (c. 1830) or A Bivouac of Travellers, in which a vivid early sketch (1827) was repainted later after his return to England (1838), are invaluable documents, but vary considerably in tone according to their genre.

Rodius’s drawings, in contrast, being simply head studies, stand outside of any genre other than pure portraiture. They can feel sympathetic but, as Hansen suggests, there is nothing sentimental about Rodius’s sympathy; it is rather a kind of respect that arises from a lucid and dispassionate devotion to truth. He does not try to make the features of his sitters prettier than they are, or more appealing to the European eye; but neither does he caricature them in any way. He presents them in such a directly matter-of-fact way that we accept them as simply different.

It is plausible to suggest that Rodius’s view of his Aboriginal subjects is connected to his experience as a Jew, and perhaps especially one from Hamburg, where the Jewish population, as already noted, played a significant part in the city’s economic life and though generally supported by the upper classes was, typically, resented by the lower. There were violent anti-Jewish riots there in the 18th century and throughout Rodius’s lifetime. At the same time, anti-Semitism was frequently (and it seems increasingly throughout the 19th century) visually expressed through the caricature of Jewish features.

Perhaps it was this kind of experience that provoked in Rodius both a fascination with distinctively different physiognomies and a determination to represent them dispassionately and without judgment.

Christopher Allen is a member of the State Library Council. Charles Rodius, Exhibition Galleries, State Library of NSW, Sydney, ends May 12 next year.