Sydney’s collection of 1001 riches: from mousetraps to great art

A Sydney exhibition is so rich with intriguing items from a vast history of mankind, it’ll keep you doubling back. But this one takes the cake.

The title of this exhibition alludes to the labyrinthine narrative structure of the 1001 Nights, the monumental collection of interconnected tales that took shape in the Perso-Arabic world some 11 centuries ago and was first published in Europe in a French translation by Antoine Galland in 1704-17. Like Scheherazade’s episodic but linked narration, the exhibition, too, is a labyrinth of small rooms filled with unexpected encounters and conjunctions.

There are in fact so many rooms and so many objects in them – all chosen on the basis of being “remarkable” items in the Museum’s vast and diverse collections – that you have to keep wandering around and going back on your tracks to make sure you haven’t missed one, and in the process you repeatedly spot things that you overlooked on the first visit, simply because your attention was drawn elsewhere.

It was only on the second time that I entered one room, for example, that I saw pieces of Ancient Greek ceramics. One of these is an Attic black-figure amphora from 530-510 BC, by which time Attic ceramics had displaced the formerly dominant and orientalising style of Corinth. The central figure is undoubtedly Demeter, goddess of cereal crops, but she is accompanied by two dancing satyrs and wreathes of ivy, reminding us of the close connection between Demeter and Dionysus that I mentioned two weeks ago.

Above this are two cylix cups for drinking wine, with their flat dish-like shapes and pairs of handles. The display reminds us of the technical vocation of this collection, for there is a clear difference in skill and refinement between the earlier piece, made in Athens around the time of the Persian Wars (490-80 BC) and the latter, made in Apulia probably in the 4th century. Apart from the superior decorative painting, the Attic piece has a taller stem, a more elegant shape, and exquisitely fine handles; the later Italian cup has a shorter stem, a heavier form and above all rather crudely reinforced handles.

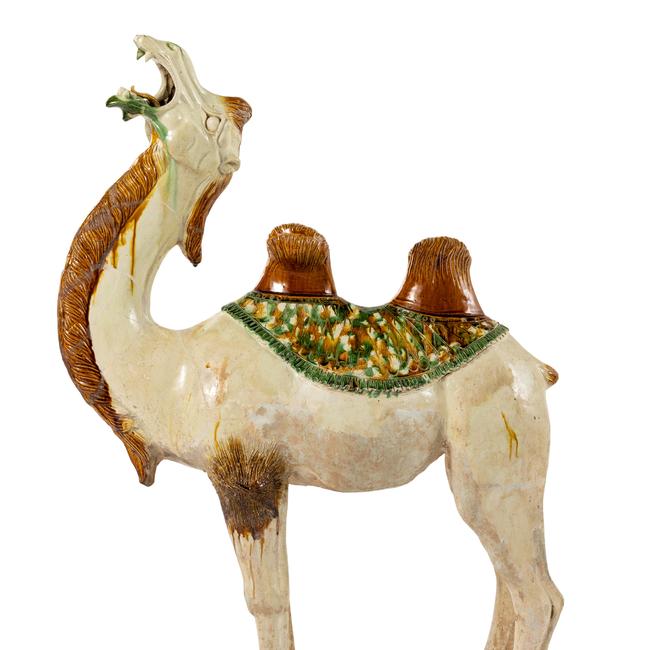

There are countless other fine examples of ceramics, in particular from East Asia, including many cups, bowls and vases, but also objects as different as an impressive Tang Dynasty Bactrian camel (618-907AD) in the characteristic three-colour glaze of the period, or a Cricket jar – effectively a ceramic cage – in enamelled and gilt Satsuma ware made in Japan around 1900; like the Greeks and the Chinese, the Japanese enjoyed keeping pet crickets for their song.

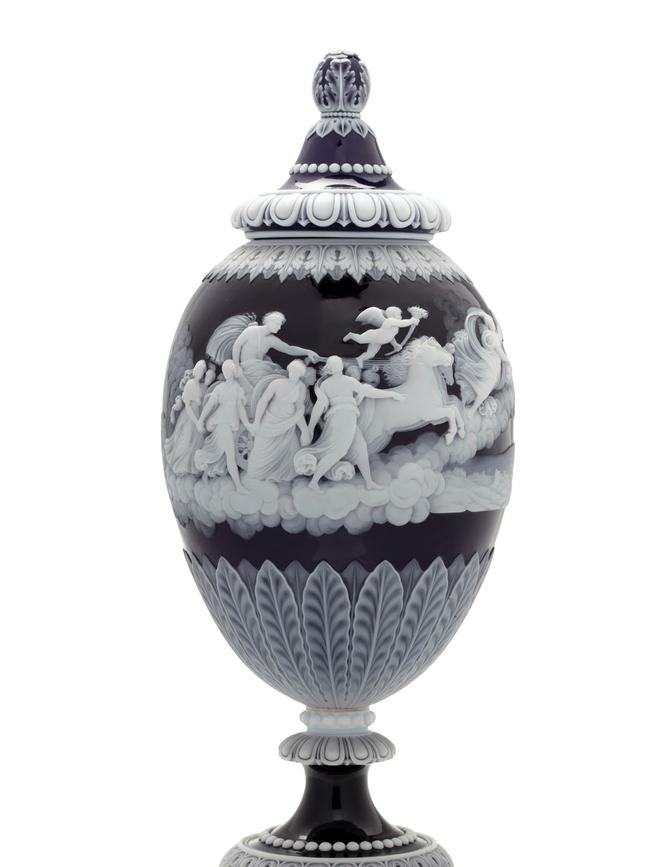

Among the many examples of European ceramics, from the simple to the extravagant, like a boar’s head tureen, some of the more outstanding pieces are by Wedgwood, currently the subject of an exhibition at the David Roche Foundation in Adelaide, Wedgwood: Master Potter to the Universe, which I hope to visit in a few weeks. A later piece, imitating Wedgwood’s cameo effect in glass, is the Aurora Vase, made by Thomas Woodall for Thomas Webb & Sons (1879); this is a reproduction of Guido Reni’s famous Aurora Fresco (1614) in the Casino dell’Aurora Pallavicini in Rome.

Painting is not prominent in a museum dedicated to the applied arts, but there is an interesting example of early 17th century Flemish landscape painting in Italy on the lid of a virginal made in Bologna in 1629, a few years after the death of the Bolognese Pope Gregory XV Ludovisi. The painting is close to the style of Paul Bril, and is an episodic and anecdotal collection of scenes of the labours and pleasures of country life.

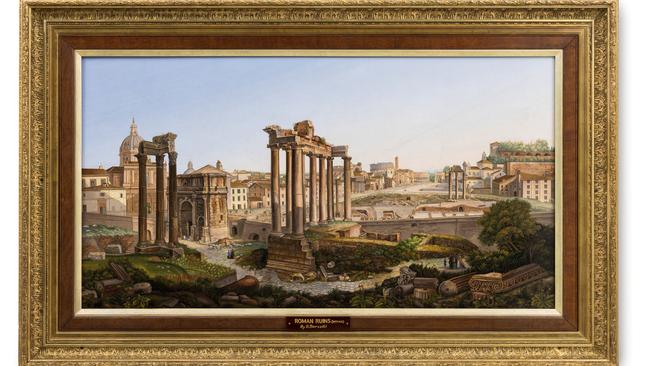

Some other images that may look like painting at first sight are actually examples of micro mosaic (glass tesserae), like almost all the altarpieces in Saint Peter’s in Rome. Thus a large cityscape by Biagio Barzotti, simply titled Roman ruins (c. 1876) is in fact a detailed and accurate view of the Roman Forum, including the three surviving columns of the Temple of Vespasian on the left, then the Arch of Septimius Severus and the portico of the Temple of Saturn, as well as the Colosseum in the background and the Arch of Titus, restored by Valadier in 1821.

Some objects evoke religious belief but also indirectly social and political themes; thus there is a sumptuous Japanese house-shrine honouring Amida Buddha, a favourite in Japan with his promise of eternal life in the Pure Land, accompanied by two Bodhisattvas. This work speaks as much of the family’s prosperity in this life as of its hopes for the next one. There is an enormous bronze bell, too, from 15th century Ming Dynasty China, recovered from the ruins of a temple in Beijing (then Peking) in the Boxer Rebellion in 1901.

Three small ornaments on a wall could escape notice but have interesting and grim associations; they are manillas, described as currency or jewellery from West Africa, and dated between 1850 and 1948. This was the African end of the transatlantic slave trade, and manillas were paid as currency to the Africans who, as in Benin, rounded up members of other tribes to sell to the slave traders. The women of the men who had enriched themselves in this way wore such manillas on arms or ankles to display their wealth and status. The dates of these items are significant, however, because Britain outlawed the seaborne slave trade with the Slave Trade Act, 1807, so the ornamental function clearly outlived the economic one.

Many things in the exhibition have less serious associations, such as the various dresses and costumes and a considerable amount of jewellery. A Sedan chair designed in France, presumably in the early 19th century – the French term is “chaise à porteurs” shows how the wealthy could be carried through wet and muddy streets by two porters without soiling their shoes. Because porters could take you up to the door of your apartment, staircases in old buildings were usually wide up to the second or third floor, and narrower after that, going up to the dwellings of the more modest classes.

One piece of furniture of outstanding interest is Governor Macquarie’s chair. This fine example of very early colonial furniture somehow ended up in the Vancouver City Museum, which generously gifted it to the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences in 1961. Macquarie’s chair should remind visitors of his role as a visionary governor determined to turn a penal colony into a city and to give convicts who had served their sentences a second chance to play a useful role in society. Of course these days we are simply told that it “serves as a sombre reminder of the violence inflicted by Governor Macquarie upon those who resisted colonial rule”.

Closely connected to the history of settlement and the development of modern Australia is an impressive display of longcase clocks, opposite which, as another device for measuring time, is a massive section cut through an ancient red cedar tree, felled in Queensland a century ago, in 1923, according to the inscription on the timber itself, which contradicts the label’s date of 1924. The tree was 350 years old, and thus allowed its growth rings to be used as a timeline of Australia’s history from almost the first Dutch landings in the early 17th century to Cook’s visit a century and a half later and then from the foundation of Sydney onwards.

The clocks themselves tell us much, too. They were not all simply handsome grandfather clocks designed to stand in the residences of the wealthy. One, for example, is a regulator clock used to measure time by the stars rather than the sun, which was made in 1808-10 and brought to Sydney in 1821 to be used at Parramatta and later Sydney Observatory. Sidereal time is more accurate than solar time, and regulator clocks, developed in England about a century before this time, used a weighted and geared mechanism to achieve a very high degree of accuracy.

This was obviously essential for astronomy, but also for navigation. A second such clock, which was made in England in 1791, was employed by George Vancouver in exploring the northwest coast of North America before being used again by Matthew Flinders in his circumnavigation of Australia in 1801-03, to check the accuracy of the chronometers whose own invention had for the first time made it possible to determine longitude accurately.

All of this reminds us that the settlement of Australia did not just introduce new technologies of agriculture, building and industry to a land where none of these things had existed, but brought entirely new ways of thinking, systems of scientific, rational and critical discourse which had never developed here, and which in fact cannot develop in pre-literate cultures.

Of course, the outcomes of rational and scientific thinking are not all beneficial, for these new powers can be used for ill as well as good. And at the same time there are no doubt things that pre-literate people know and understand which can be lost in the brave new world of science and progress. But once a new kind of thinking has implanted itself, there is no turning back to a time of primal innocence.

One device in the exhibition that evokes the loss of individuality and humanity in the modern industrial world is the Bundy machine, which allowed companies to know exactly when an employee had “clocked on” or “clocked off”, or indeed had “Bundied on”, an expression that was very common a few decades ago but seems to have fallen out of use in the digital age.

There are more whimsical timekeeping devices, particularly two alarm clocks that incorporate kettles so that the clock can wake you up with a cup of tea, or at least with boiling water for tea. The more charming of these is made in copper for the kettle, brass and mahogany, and was manufactured in 1902 by the Automatic Water Boiler Company in Birmingham. Evidently the kettle must have tipped down, lighting a methylated spirit lamp, some minutes before the alarm went off.

The other device has the brand name Teasmade, is in white plastic and chromed metal, and belongs to the 1960s. This one must work electrically and presumably pours boiling water over tea leaves, so that you awake to a cup ready to drink. But if this and a few other things are amusingly eccentric, there is one device that is not just truly remarkable, but without doubt the most bizarre in the exhibition.

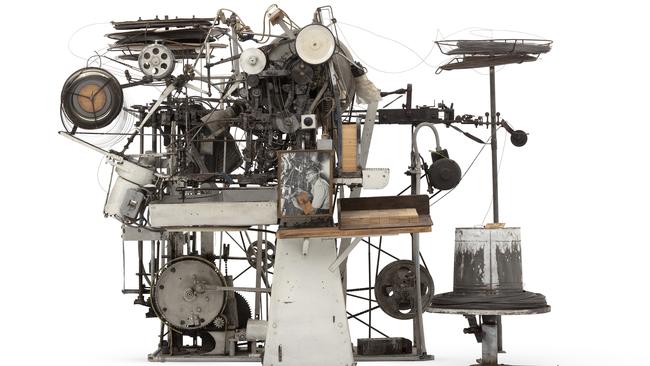

The “Supreme” mousetrap making machine looks like a spoof, so complicated that it’s hard to imagine how it even worked, let alone that it could produce anything. And yet a little research proves that its inventor, A.W. Standfield, used it to make a trap in 1.5 seconds, and could turn out 1000 an hour. He was, in fact, not only the inventor of a better mousetrap, but of a better machine for making mousetraps.

1001 Remarkable Objects

Powerhouse Museum, Sydney, until December 31

This page: Powerhouse collection/Ryan Hernandez.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout