David Wenham, Ned Kelly and a tortured artist

A decade after his death, Adam Cullen’s work is emblematic of a painter who suffered from terrible health problems and psychological anguish.

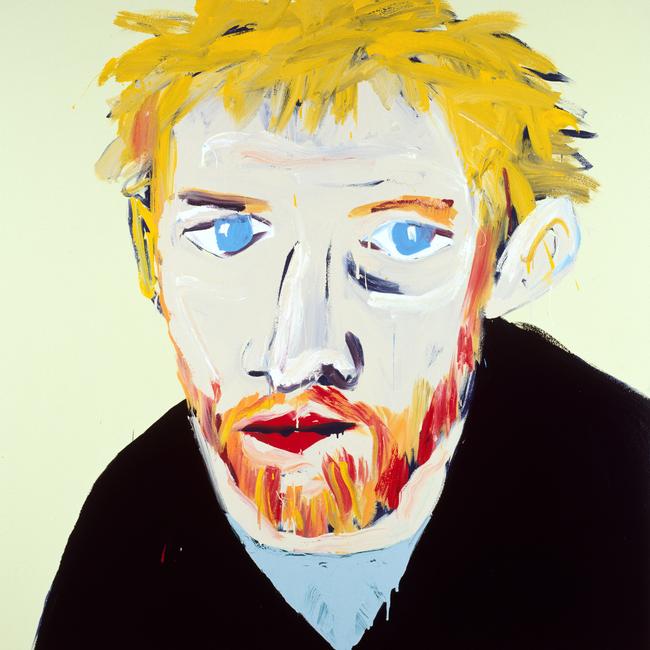

In his lifetime, Adam Cullen (1965-2012) was notorious for his violent, lurid and provocatively ugly paintings, although his best-known picture, the portrait of David Wenham with which he won the Archibald Prize in 2000, avoids the more extreme features of his style. Now, just over a decade after his death, the retrospective at Manly Art Gallery is an opportunity to reconsider his work and its place in the history of recent art.

One’s first impression may be of very big, loud compositions dominated by one or two cartoon-like figures painted in a sometimes hysterically expressionist style, evoking menace, fear or anguish. There are ghoul-like creatures, a knight with a sword dripping in blood, horse heads recalling Picasso, grotesque male and female creatures with crudely distorted facial and sexual features.

And yet there is also a self-consciously decorative quality to these pictures which verges on camp; they are generally painted on a brightly coloured and flat background, and outlined in black which makes the figure stand out as a pattern. The exhibition includes a film which is interesting in revealing Cullen’s process: he first paints the figures in various colours, some of which are destined to be covered over by further layers and only show through here and there, but without edges or boundaries.

The black is painted on afterwards, defining forms – like the shape of a helmet and the slit for the eyes in a Ned Kelly image – but also turning the whole thing into a pattern, neatly finished and complete, ready for sale to a collector who is looking for something edgy and provocative but which will still be striking as an object in an interior. At the same time, in case this tidy pattern-making seems too facile, the works are covered in dribbles of wet paint running down the picture surface, a gimmick that is pervasive in Cullen’s work as in that of many other painters before and since.

For all this, there is an undeniable intensity of feeling in Cullen’s work. The sense of fear, anguish and horror is not a mere affectation as it was in the work of some other artists who were drawn to schlock subject-matter in the postmodern period. In the latter years of his relatively short life, Cullen suffered from terrible health problems and was frequently in hospital; but well before that he was subject to psychological anguish and disturbances that led him to extremes of alcoholism and drug abuse.

The story is told in Erik Jensen’s biography of the artist, Acute Misfortune: The Life and Death of Adam Cullen (2015), but readers will probably find all they need to know in an excerpt of this book published in The Sydney Morning Herald in 2014, easily found on the web by searching for “Adam Cullen secret desires”. Jensen’s account reveals a complex man who was a loner but also lonely, had several relationships with women but didn’t really like them, and was struggling with semi-repressed homosexual desires. All of this helps to explain some of the lurid imagery in his paintings, but Cullen also has to be understood within the broader context of art in the last decades of the 20th century.

The postwar years were a period of rapidly changing fashions in art, and because it was assumed that they were all part of a linear succession in a teleological race towards the end of art history, each was accompanied by heated and, in hindsight, futile theoretical arguments about its validity and claim to represent the final consummation.

Thus painterly abstraction was replaced, in the later 1960s, by post-painterly flat compositions, and barely had that movement celebrated its apparent triumph (in Australia with The Field exhibition in 1968) when fashion moved on again to pop, minimalism, conceptual art, performance art, political posters and so on, in a final gallop towards the seemingly post-historical swamp of what became known in the 1980s as postmodernism.

Meanwhile painting – soon after its flat apotheosis – had yet again been declared dead by the conceptualists, minimalists, performance artists and others. A few years later, though, by the late 1970s, it was back again, but in a new guise, variously labelled “bad painting”, the title of an exhibition in 1978 by Marcia Tucker, neo-expressionism and other names in Italy and Germany. Many of Tucker’s original artists are almost completely forgotten today, but the dominant figures of this movement in America included David Salle, Julian Schnabel and Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Most of the work these artists produced was of questionable aesthetic value, and after the brief revolt of the conceptualists and minimalists against the commodification of art, the bad painters, neo-expressionists and their kind all enthusiastically embraced the production of commodified, abundant and highly formulaic art for a voracious market of rich collectors, eager as always to demonstrate their wealth, status and sophistication through the purchase of work marketed as challenging and controversial.

Leaving aside the brazen market abuses of this period, so acerbically criticised at the time by Robert Hughes, the deeper significance of this whole movement was in bringing back figuration after the austere decades of the reign of abstraction. Artists all over the world rediscovered the fact that representing the natural environment and human bodies offered greater expressive potential than painting patterns or gestures with little or no reference to the universe of ordinary human experience.

Minimalism and subtlety were replaced by maximalism and exaggeration; the body returned in caricatural form. It’s tempting to say that when it was realised that painting wasn’t dead after all, it was a kind of zombie-painting that rose from the grave, half-decomposed and still scarred by its season in hell.

These artists drew on earlier traditions of expressionist painting, but also on the most popular figurative idioms that had continued to dominate narrative art at the mass or kitsch level, that is cartooning, first in print and then increasingly in animation and on television. Hence some of the deliberately ugly and formulaic elements that are borrowed by bad and neo-expressionist painting, from mainstream cartoons as well as alternative ones such as Ren and Stimpy or Beavis and Butthead. From the high art tradition they could also look to the anguished distortions of Francis Bacon.

As for Cullen, a first glance may suggest that he has little to offer beside rage, self-pity and simplistic resentment – evident, for example, in his caricatural figures of a lawyer and a magistrate. Nor does he have much to say about the natural world or the normal range of human experience. His figures are inevitably grotesque caricatures and his evocation of the feminine is violently misogynistic, as though the female can only appear as the monstrous.

Looking at his work again after many years, its most substantial core is clearly in his representation of himself, his life and his sufferings. Unappealing as it may be in many ways, we cannot forget the intensity of suffering and the sense of abjection evoked in 2007 in Saladin (why we kill Arabs), in which the artist represents himself sitting naked on the toilet, marked with the multiple scars from recent operations, next to an armoured medieval king that the exhibition’s curator interprets as an image of his surgeon.

In a couple of other works he again evokes the middle ages, and seems to see himself as a kind of modern Knight Templar, invested with a sacred mission but doomed to be killed. The Templar helmet is clearly the motif that led him to adopt the legend of Ned Kelly as a vehicle for his own sense of tragic destiny; we can witness the fusion of the two subjects in Horned Kelly (2011), one of the pictures that we see him painting in the film.

The Kelly helmet appears in several other pictures, such as Kelly with mare (2011), and in all cases it evokes a profound sense of vulnerability and withdrawal. What is behind the impenetrable mask is not just human suffering and fear, but something far more irredeemable, hinted at in the amorphous and decomposing features of Perdition No. 4 (Kelly Death Mask), also from 2011. Cullen is not romanticising Kelly as a Robin Hood figure, but imagining him as someone, like himself, enduring a state of intolerable suffering and living death.

Still more disturbing is the much bigger Missing Kelly skull (2011), painted as though to look like something from a B-grade horror film. This is another picture that we can watch him painting in the documentary, and it is interesting to see how an image that appears to evoke an almost hysterical sense of pain and terror at the approach of death is in fact being executed methodically and systematically, as though putting together a decorative composition of flowers in a vase, while glancing at a photograph pinned on his left to define the highlights on the bony ridges of the skull.

This is no doubt an illustration of the exhibition’s subtitle: art is pain relief. The idea that we rise above the immediacy of pain by expressing it in writing, music or painting, is of course a very old one. It was by all accounts not enough of a pain relief all by itself, though, since Jensen speaks of the quantities of alcohol and drugs that Cullen needed to take before he could face painting at all. In any case, with the combination of techniques for pain relief, we can see how these ostensibly expressionistic paintings are actually produced in a way that seems almost antithetical to such a style, yet clearly reflects the way that turbulent and even unbearably painful feelings have been tamed and contained in these stable, finite objects with their hard black decorator outlines.

It is curious to reflect on whether Cullen would have had the same impact if he started his career today, when the art world has become so preoccupied with moral posturing and ideologies of identity and diversity, and increasingly run by bureaucrats and so-called curators. Interestingly, Australia still has a number of relatively prominent exponents of bad painting or neo-expressionism but they are all well-behaved these days and realise that woke zeal is what the gatekeepers want to see, not cynical nihilism and existential anguish.

One of the unfortunate enduring effects of bad painting, however, has been to persuade many people that this is the only kind of painting that can be taken seriously as modern practice.

Half a century after the zombie-paintings rose from their dank graves and stalked across the blasted wasteland of late modernism, it may be time to think again about this matter. And in fact a great many contemporary painters are rediscovering the potential of the art of painting as an instrument for understanding the natural world as well as the human heart, even if the news hasn’t yet reached the wardens of our institutions.

Adam Cullen: Art is Pain Relief, Manly Art Gallery, Sydney, until December 3.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout