The Brown Collection: a gift that keeps giving

The collection of 154 pieces of art given by Melbourne art dealer Joseph Brown to the National Gallery of Victoria reveals a taste that was open and even eclectic.

A little more than a week ago, a regional gallery in Victoria offered several paintings and sculptures from its collection at the Deutscher and Hackett auction of August 28 in Melbourne. De-accessioning works from a public museum is unusual enough, but what was surprising about this sale was that the works disposed of were all of very high quality and normally should have been considered valuable parts of a core collection, not minor odds and ends. In addition, most of the works were gifts, the remainder being recent acquisitions.

McClelland Sculpture Park and Gallery, at Langwarrin near Frankston in Melbourne, was selling Clarice Beckett’s Boats at Sunset (1930), given to the collection by the artist’s friend, John Farmer, in 1971; Emanuel Phillips Fox’s Vanity (c. 1912), given by Dame Elisabeth Murdoch in 1979; Rupert Bunny’s The Telegram (c. 1908), given in memory of a deceased relative in 1977; Bertram Mackennal’s Circe (c. 1902-04), purchased by the gallery in 2010; Mackennal’s Truth (1894), purchased by the gallery in 2010; Mackennal’s Salome (1897), purchased by the gallery in 1992; and Frederick McCubbin’s Rainbow over Burnley (1910), also given by Dame Elisabeth in 1989.

This sale raises several important questions about the ethics and governance of public collections. The most obvious, of course, concerns the sale of works that were originally given to an institution. Another is when works were purchased, especially recently, suggesting a lack of consistent or long-term vision for the collection. It is the board’s responsibility to oversee the strategic direction of an institution and to prevent ill-judged decisions being made at the whim of whoever happens to be director at a given time.

Particularly surprising, in this case, is that three of the pieces sold, including the most recently purchased, were sculptures, and that they represent an important piece of the history of Australian sculpture: Mackennal, who was born in Melbourne, became a highly successful sculptor in Britain but also designed, among other things, the Cenotaph in Martin Place in Sydney. Clearly the recent acquisitions were made – by the previous director – with a view to building a more complete historical collection.

The vision of the present director is less clear. In a note contributed to the auction catalogue, she acknowledges the importance of the historical sculpture collection and the Elisabeth Murdoch Sculpture Foundation, which helped to fund the purchase of one of the pieces now being sold. But the penultimate paragraph reveals the truth: here she speaks of “spatial practice” and declares the gallery is now “a place of social exchange” and “a forum for discourse about culture”. Inevitably there is a reference to Indigenous culture, once again credited as the oldest culture on earth – ignoring, of course, the fact that all cultures are ultimately equally old, only the great majority of them have changed and developed while a few have not.

We can sense in these remarks an increasingly common anti-historical bias, as though the dynamism inherent in the historical development of civilisations were morally compromised compared with the imagined innocence of prehistoric cultures. While past generations may have indulged in a triumphalist account of the foundation of Australia, today the cultural classes, haunted by guilt and illegitimacy, take refuge in sentimental illusions of primitivism. Australian art history has suffered particularly badly since it is above all the story of learning to inhabit a new land; the takeover of the Wynne Prize for landscape by bland dot paintings represents an erasure of the history of Australian landscape painting and an implicit denial that anyone who has come here in the past quarter millennium can form a valid relationship with our land.

On the subject of collections, this year marks the 20th anniversary of the most important single gift of works of art to an Australian public collection. In 2004 Melbourne art dealer and collector Joseph Brown gave the National Gallery of Victoria 154 pieces, including paintings, drawings and sculptures. These have always been exhibited, as is appropriate, as a separate collection and recently have been rehung in a new display on the top level of the NGV Australia building.

Brown (1918-2009) was born in Lodz, Poland as Josef Braun and migrated to Australia in 1933 at the age of 15 with his father and siblings, a couple of months after his mother’s death. He enrolled in art classes with Napier Waller from 1934 until his studies were interrupted by the Depression, and later joined the Australian Army in 1940, serving with the 13th Armoured Regiment until 1945. After the war he started a fashion business while still continuing to paint and sculpt. In 1967, however, he sold the business, bought Caroline House, a Victorian mansion in South Yarra, and opened the Joseph Brown Gallery at 5 Collins Street, Melbourne. All the while he continued to build his own private collection, of which he had given more than 400 works to public galleries even before the final gift to the NGV.

One of the distinctive qualities of Brown’s taste, both as dealer and collector, was that it was so open and even eclectic. This was a time of rapidly changing art fashions, when writing about art was often dominated by strident quarrels between different schools of abstraction, and when those who considered themselves the spokesmen of the avant-garde – retrospectively in its death throes – were contemptuously dismissive of anything that did not match their narrow and increasingly sterile conception of painting.

Jeffrey Smart remembered how depressing those years were, when art publications were entirely monopolised by abstract paintings, and the kind of thing he and many others were doing was barely taken seriously. But Brown had a broader perspective; as he said, he was not interested in fashions but only in whether a given painter had made a contribution to the history of Australian art.

Consequently, although he was himself an abstract artist, he saw the value of Smart and others, who like Balthus, Lucian Freud and David Hockney, have ended up being more highly regarded than almost all their abstract contemporaries.

The same breadth of taste led him to appreciate colonial artists from John Glover to Eugene von Guerard; today there is nothing unusual in admiring these significant figures, but we have to remember that the third quarter of the 20th century represented the nadir of their reputations.

Von Guerard is a touchstone: in the first edition of Alan McCulloch’s Encyclopedia of Australian Art (1968) he is perfunctorily discussed in a few paragraphs; in Robert Hughes’s youthful The Art of Australia (1966) he is dismissed as a dull academic artist. It was not until the 1980s that von Guerard’s importance was rediscovered, with Candace Bruce’s Eugen von Guerard (1980) and Tim Bonyhady’s Images in Opposition (1985), and his rehabilitation as a central figure in Australian art history was confirmed by Ruth Pullin’s Nature Revealed (2011) followed by Pullin’s The Artist as Traveller (2018).

Brown owned a couple of beautiful landscapes by the artist from the height of his career, Spring in the Valley of the Mitta Mitta (1863) and Yalla-y-Poora (1864), a fine portrait of a colonial estate; the property belonged to the Ware family, one of the first to settle the Western District of Victoria. The collection also includes a handsome portrait of JG Ware, attributed to Thomas Flintoff, from the same years (c. 1865).

Brown owned many other colonial paintings, such as Glover’s A Mountain Torrent (c. 1837), recalling the earlier colonial period, and Abram-Louis Buvelot’s Bush Track, Dromana (1875), representing the style that came to supersede von Guerard’s in colonial taste and prepare the way for the Heidelberg School. There are works by Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton, but they are often more curious and less obvious examples of their style, such as A Moorish Doorway by Roberts (1883), painted in Spain not long before he returned to Australia in 1885 to establish the Heidelberg movement, or Streeton’s Tambourine (1891), a glimpse of Roberts’ studio at Grosvenor Chambers in Collins Street, Melbourne.

Brown was also instrumental, as early as 1968, in restoring the reputation of another important Australian artist, largely forgotten because he had lived most of his life as an expatriate, with the exhibition John Peter Russell 1858-1930: Australian Impressionist; this was the precursor to the more recent John Russell: Australia’s French Impressionist (2018) by Wayne Tunnicliffe, which helped establish the artist’s standing for a new generation of art lovers. And he was prescient in appreciating the talent of painters such as George Lambert and Hugh Ramsay who, like so many others, have been more widely understood following survey exhibitions in recent decades – Lambert in 2007 and Ramsay in 2019-20, both at the NGA in those pre-Covid years when our most important galleries were still interested in Australian art history.

Brown was just as perceptive in collecting works by the modernists of the interwar period, the war years and the decade following the war that produced so many remarkable works by Arthur Boyd, Russell Drysdale and Sidney Nolan. All of these artists were ignored by the ideologues of abstract painting, even if the last three were establishing reputations and careers in England beyond the parochialism of Australian art fashions.

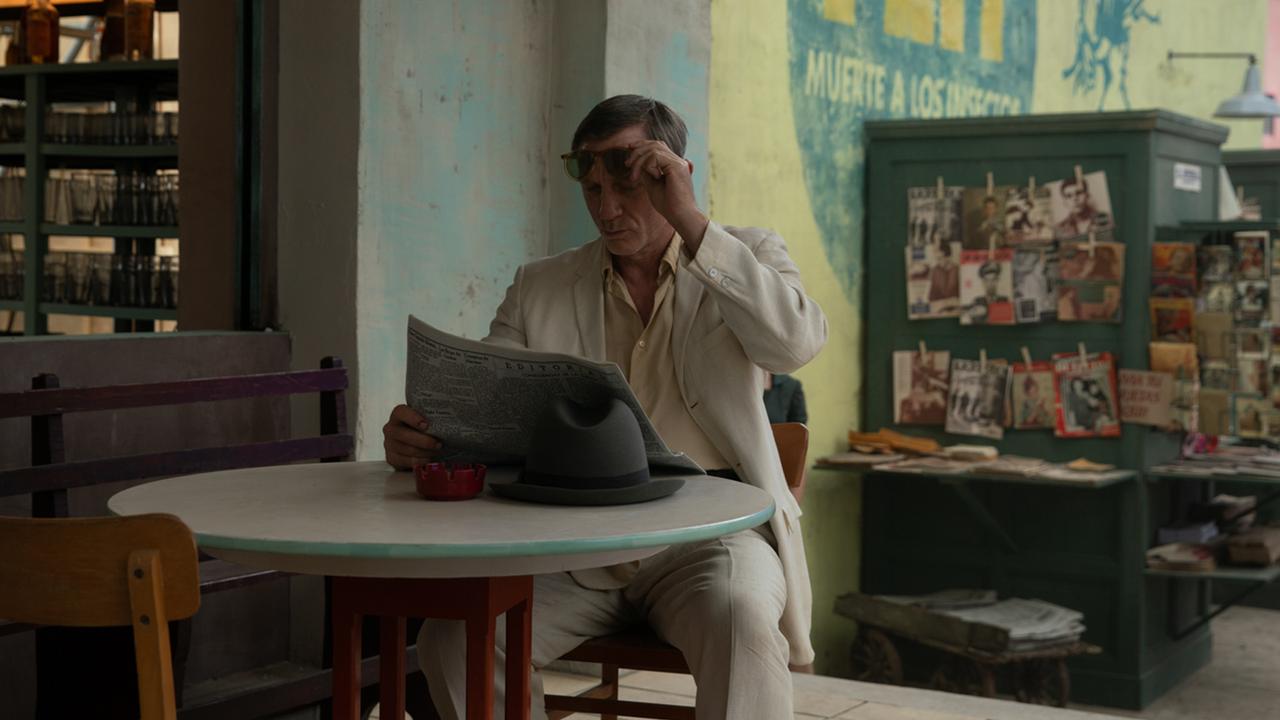

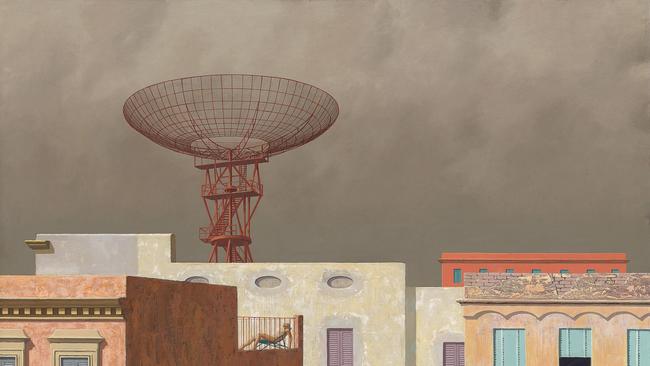

Thus we find Grace Cossington-Smith, Yosl Bergner, Godfrey Miller, Drysdale, Boyd, Albert Tucker and others from these decades; other important modernist realists, for want of a better word, include John Brack with The Block (1954) and Smart with Rooftops (1968-69), a work from his earlier years in Italy, in which a contemporary radio dish sits high above a cityscape of stuccoed Roman houses, while a single naked figure is seen sunbathing on a rooftop.

Of course not all the pictures in a collection such as this will delight us equally; some may represent styles that have not aged as well as others. But that is to be expected in a collection that represents a combination of personal judgment and a sense of what is significant in any period.

Personal judgment will never be infallible, but it tends to be more reliable in the long run than the groupthink of institutions, whose policies and guidelines are mainly intended to evade the responsibility of taste and discrimination.

We are fortunate that the terms of Brown’s gift stipulated that the collection be displayed together, in whole, and in dedicated rooms.

This preserves its unique character as a true collection, assembled by an individual with passion and dedication and not by a committee. And I think it is safe to say that works from the Joseph Brown collection are not going to be slipping surreptitiously out the door and into an auction catalogue because some museum director, incumbent for a few short years, wants to raise funds to establish a “a place of social exchange” or “a forum for discourse about culture”.