Broad human canvas covers history of Australian art

SASHA Grishin’s new book, Australian Art: A History is huge yet it would be hard to argue it is too long: it is the scale the subject demands.

WHEN reviewing a book on a subject on which one has also published a work, it is probably prudent to begin by acknowledging the fact. My Art in Australia from Colonisation to Postmodernism (Thames and Hudson, 1997) was commissioned by Nikos Stangos, who had about three decades earlier commissioned Robert Hughes’s Art of Australia (1966). In fact Stangos saw my book as in some sense a replacement for Hughes’s volume, taking into account not only another 30 years of contemporary art but also the significant re-evaluation of Australian colonial art in the last decades of the 20th century.

As part of the World of Art series, my book was necessarily concise, conceived as an accessible introduction to the subject. My intention was to propose a way of reading the history of Australian art, a narrative that stressed the intrinsic concerns of artists in this land rather than seeing Australian art as a series of colonial, and later provincial, reflections of art-historical developments in metropolitan centres.

Sasha Grishin’s new book, Australian Art: A History, is very different in scale, in ambition and in its historiographical approach. And in the first place, if my book was meant to take the place of Hughes’s short introduction, Grishin’s is intended to replace Bernard Smith’s Australian Painting (1962), hitherto the greatest synthetic vision of the development of art in Australia. Grishin’s book is neither an introduction nor an interpretative essay, but a full-scale history of art in Australia.

When I arrived in London to see Stangos, a Customs officer asked me the purpose of my visit. When I said that it was for a book on Australian art, he replied without missing a beat, ‘‘That would be slim volume, then, sir.’’ In fact, Australian art is far from a small topic and Grishin’s book is certainly not a slim volume. It is huge and enormously heavy, and yet it would be hard to argue that it is too long: it is simply the scale the subject demands if it is to be covered in the degree of detail he has set himself.

The scale of a history, of course, is like that of a map: it can be greater or smaller depending on what one wants to achieve. On a map of a small scale, it is easier to see the shape of a country but hard to make out any but the biggest mountain ranges, rivers and cities; on a very detailed map, even small topographical features and modest towns and villages may appear, but it will be harder to grasp the overall shape of the land. In a history, concision will favour the sketching of a vue d’ensemble, but greater length is more congenial to the empirical historian who is concerned to gather all the facts in the most objective way possible. Grishin, professor of art history at the Australian National University, is essentially empirical rather than interpretative in his approach, and he has succeeded in marshalling a vast amount of research, impressive in its detail and its accuracy, into a structure that presents periods and movements in an intelligible way, while focusing largely on a series of individual studies in a manner that makes the book useful and convenient as a reference work.

In a shorter survey, the biographical circumstances of an artist’s life can only be briefly outlined, and their oeuvre frequently has to be reduced to one or two works that epitomise their contribution to the overall story. In a history of this nature, there is room to discuss the upbringing, artistic development and career of each significant individual including, importantly, the date and circumstances of their death. There is space to acknowledge personal and aesthetic complexities, as well to recognise that an artist’s career extends beyond the years when his work occupied the limelight of fashion or the forefront of the avant-garde: time and again, artists have grown from young rebels into members of an art establishment that does not always welcome the following generation.

One of the great virtues of this book, in fact, is the author’s ability to enter into the spirit of the successive periods and to sympathise with the artists he writes about. Far from the complacency of hindsight too often encountered, especially in accounts of modernism, Grishin has the historical imagination to see things from the point of view of the artists and others that he is writing about, which does not mean that he is uncritical. The right balance between criticism and sympathy is important in dealing with any period or individual, and a degree of sympathy can itself allow criticism to be deeper, rather than merely harsh or strident.

In any case, it is one of the most attractive features of Grishin’s work that he engages in such a generous spirit with the artists whose careers and work he deals with. Without being exactly an advocate for each individual, one does feel at least the author has situated them in their time and explained their work, interests and style in a way that presents the best plausible case for their claim to our attention.

The way that artists of one generation influence and are in turn judged by those of successive ones is always important, but the question becomes more complex than ever, and often fraught with difficulties, in the modern period, because of the rapidity with which new styles appear and challenge the authority of those who had come before. At the same time, there are often conflicting perspectives even within what can seem from the outside like a coherent group: witness the intense closeness of Sidney Nolan and Albert Tucker to John and Sunday Reed, and their later antagonism, or indeed the way that Lionel Lindsay and JS Macdonald, often assumed to be fellow arch-conservatives, were on different sides in the quarrel over William Dobell’s portrait of Joshua Smith.

These questions of reception and conflicting or diverse perspective, though discussed at length, are still more effectively illustrated by substantial citations of contemporary writings. The use of such primary documents, from reviews, letters, novels, memoirs and other sources, helps to leaven what would otherwise be an immensely long text, but most importantly they provide invaluable insights into the thinking of people at the time. You realise on reading these original passages how much would have been lost in merely paraphrasing them: how difficult, indeed, it would be to summarise their meaning without intrusively simplifying or caricaturing them. The reproduction of judiciously selected passages allows us to appreciate not only the main assertions of an author but also the unspoken assumptions on which they are based, and nuances of connotation that could not be conveyed in any other way.

Such original texts, then, allow us to enter into the mentality and culture of the time, with the expression of ideals and hopes which could seem cliched or sentimental in paraphrase, but they also serve to convey the exact tone of critical responses, whether appreciative or dismissive, and to let us hear for ourselves the voices of praise, blame, ideology and even at times odious prejudice. Freed from the need to editorialise, the author can let his subjects speak for themselves while remaining relatively aloof and impartial.

This impartiality is admirable when it comes to dealing with the controversies of the past, in which the historian needs to be free of the prejudices and passions of the original participants. Apart from anything else, we can see with the advantage of distance that few positions are absolutely right or wrong, and even those we now broadly disagree with may contain elements of truth. A classic case would be the debates between social realists and avant-gardists, or the repeated tensions between traditionalists and modernists — where, as we have seen, yesterday’s ‘‘progressives’’ so quickly become tomorrow’s ‘‘conservatives’’.

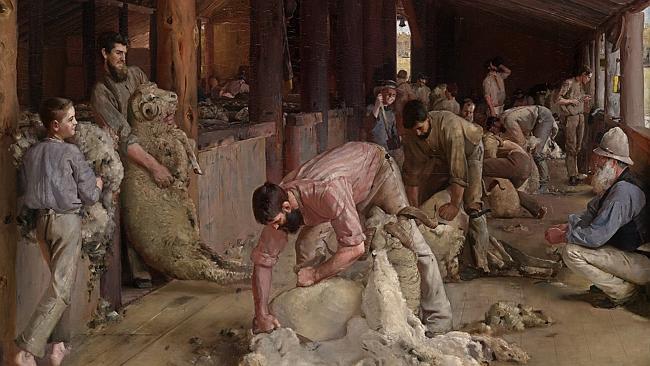

On the other hand, the same outlook that leads to this even-handedness seems to entail a certain reticence or agnosticism about ideas, interpretation and meaning in general. I would, to take only one prominent example, emphasise the theme of labour in Heidelberg painting, and the way the symbolism of the axe is carried from Louis Buvelot to Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton, ending up in Frederick McCubbin’s The Pioneer. That theme — with its corresponding leitmotif — also lends special significance not only to Streeton’s later paintings of great trees ingloriously cut down by mechanical saws, but to Nolan’s Ned Kelly, who can be read as the inversion of the Heidelberg selector: the honest worker who gains the right to feel at home in the new land as against the outlaw who embodies alienation.

Indeed, Grishin does not seek to advance any general thesis about the meaning or direction of Australian art, except for the assertion that it should include Aboriginal art, unlike almost all previous histories. In consequence he begins his book with a detailed and very useful introduction to the subject of traditional Aboriginal art, in particular ancient cave paintings and rock engravings. Equally valuable is the discussion of the European reception of this art from the earliest days of colonisation.

What is less convincing, however, is the claim that ‘‘a continuous process of dialectics can be observed between the indigenous and non-indigenous traditions of art-making in Australia’’. This proves difficult to sustain, for although the Aborigines figure ubiquitously in colonial art, they fade from sight a generation before Federation and remain largely invisible for some 60 or 70 years, until Yosl Bergner and later Arthur Boyd and Russell Drysdale, a fact that is surely significant. The commercial and critical success of Aboriginal painting since the 1970s is certainly an important phenomenon, but its connection to mainstream Euro-Australian art has remained tangential.

One will always have some reservations about the way another person tells a familiar story, but in this case they mostly concern matters of omission, and one’s overriding impression of this book cannot fail to be one of admiration. Grishin has successfully undertaken an enormous task, requiring not only a comprehensive mastery of the secondary literature but in most cases, clearly, a return to the bedrock of primary sources.

His analysis of evolving standards of taste in successive historical periods, and of the politics of patronage dominated by one elite after another, is clear and non-partisan because he knows better than to identify with, or indeed to demonise, any of them. Consequently his accounts of important, and at the time divisive, events such as the Antipodean Exhibition in 1959 or The Field in 1968 are fresh and illuminated from unexpected angles.

There are particular difficulties involved in writing the last chapters of a history that continues up to the author’s own time, because recent and current events are too close to see in the perspective which only time will afford. It is hard, therefore, to be sure who the most important practitioners are and which directions will prove fruitful or sterile. One thing Grishin does make very clear, however, is that the contemporary art establishment behaves like all those that came before it: favoured individuals are funded, promoted and given important commissions, while others are ignored.

This book is, then, an outstanding achievement that presents the development of Australian art both in the general context of Australian history and the specific context of the politics of what gradually becomes the art world. Within this framework, the studies of individual artists are striking for the author’s genuine feeling for the humanity, the aspirations and trials, of each man or woman. But perhaps most attractive of all is Grishin’s response to the intrinsic qualities of the works he discusses: he looks at paintings, sculptures, prints and other works with a sensitivity to the way that they crystallise experience and imaginative insight in the unique material form of their making. This is, in consequence, a book that can be read not only with historical interest but with the pleasure of aesthetic discovery.

Christopher Allen is The Australian’s national art critic.

Australian Art: A History

By Sasha Grishin

The Miegunyah Press, 584pp, $175 (HB)