Hawkesbury Regional Gallery: an art exhibition worth the drive

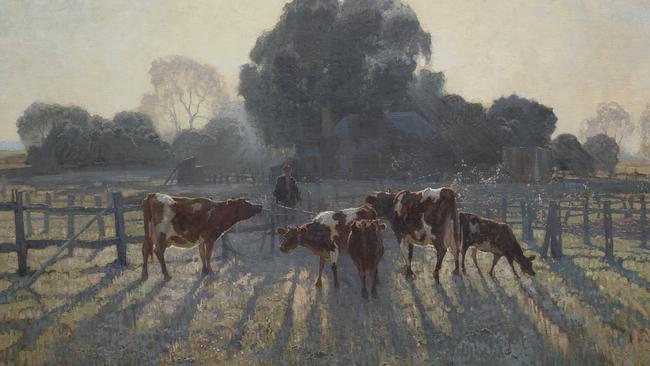

There is more to this picture than remarkable observation of natural phenomena.

The difficulties of interstate travel in a resurgent epidemic, and the closure of the National Gallery of Victoria, are severely limiting the number of exhibitions that any of us can visit at the moment. But fortunately there are a few things worth seeing, sometimes in galleries that have not been reviewed in this column for some time, if at all. One of these is Fieldwork at the Hawkesbury Regional Gallery.

The gallery is at Windsor, one of the earliest settlements outside Sydney. Within six weeks of landing at Sydney Cove, Governor Philip sailed north in a cutter in search of better farm land, initially exploring Broken Bay and the mouth of the Hawkesbury River as far as Dangar Island in March 1788. In June of 1789, Philip made a second exploratory voyage, this time sailing further upstream, coming upon the mouth of the Macdonald River – originally known as the First Branch – and continuing inland past Windsor, which he named Green Hills.

Land along the Macdonald River was soon settled and became St Albans, but the area around Windsor was far more extensive and thus more important for farming purposes: Philip saw the potential of the flat open plains to supply the colony with wheat and the navigable river allowed produce to be transported relatively easily to the colony by ship. Settlement began almost immediately in 1791, and the town of Windsor was proclaimed by Governor Macquarie during his visit to the region in November 1810.

A couple of generations later, in the third quarter of the 19th century, the expansion of the railway system in NSW made access to this and other inland parts of the colony far quicker and more convenient than it had been before. As in Europe, trains not only contributed to the growth of trade and business, but allowed urban populations to escape from growing cities to enjoy a holiday, a weekend or even a day at the seaside or in the country.

Artists took advantage of the new access to painting sites: just as the Impressionists left Paris for the forest of Fontainebleau, the lower reaches of the Seine or for Normandy, Australian painters took the train to the suburban or rural fringes of our own big cities. The Heidelberg group of painters took their name from the rural area outside Melbourne that is today a suburb. In Sydney, painters could now easily visit the Blue Mountains and other inland areas: the line to Windsor and Richmond was opened in 1864.

Train travel was thus opening access to new landscape sites even during what we consider the high colonial period of Australian art, and it was taken for granted by the time of the Heidelberg movement of Roberts and Streeton – often misleadingly referred to as Australian impressionism but really something quite different and local – whose high point was in the decade or so after 1885.

One of Arthur Streeton’s most celebrated works – The Purple noon’s transparent might, with its title taken from a poem by Shelley, was painted near Windsor in a state of “artistic intoxication” exacerbated by the extreme heat, over the course of two days in early 1896. We visited a park which is now known as Streeton Lookout, a small section of the upper bank of the river that was saved when the rest was subdivided in the 1950s for the pitifully ugly suburban dwellings that now cover it. Windsor and its region have been ruined, like so many Australian regional towns, by the unprincipled greed and short-sightedness of developers and the incompetence or corruption of successive local governments since the War.

It is not easy to identify Streeton’s precise vantage point, partly because the painting gives the impression that we are looking up a stretch of the river flowing away from us and into depth, while in fact the river runs along directly under the park, so the painter was somewhere on the bank looking to his right. At any rate the viewpoint was not within the present park, because the Blue Mountains in the distance are not in the right orientation; Streeton was probably a little further to the right, in the area now built over.

This picture would have been a natural inclusion in an exhibition devoted to landscapes painted in this region to the west of Sydney, but unfortunately it belongs to the NGV and this is a travelling exhibition made up mostly of pictures from the AGNSW. It is indeed a little disappointing that the exhibition includes no work by Streeton, but it does have many other fine paintings by contemporaries and is worth a visit which can include a look at what’s left of Windsor and of the surrounding countryside, parts of which look much as they must have a century or two ago.

What is most interesting in the exhibition is to see how successive artists encountered this new country and made sense of it. Given the historical range of the exhibition, there are a few works from the colonial period and others from what, in the absence of the principal Heidelberg painters, we can broadly characterise as plein-air painters, from the 1880s to the 1920s.

One of the earliest images in the exhibition is a view of the interior of Jenolan Caves (1883) by Lucien Henry, who was lucky to escape execution for his part in the Paris Commune of early 1871, was transported to New Caledonia and eventually came to Sydney, where he was appointed head of what is now the National Art School. Henry’s picture of the vast darkness of the cave’s interior is emphasised by the scale of the visitors on the lower left and the tiny climbing figures silhouetted against the light above.

Like Henry, Piguenit emphasises the romantic feeling of the sublime in his view of the Upper Nepean (1889) – painted in the same year as the 9 x 5 exhibition but showing no awareness of the new style. Piguenit evokes the darkness and terror of the rocky gorge and the flowing water, and above all the sublime cloudscape above; as in many romantic paintings, two small rueckenfigur picking their way along the rocks invite the viewer to enter into the mood of the picture.

Next to this is a painting of Burragorang Valley by J.H. Carse who, although earlier (1879) is less romantic and more documentary in his approach: the river runs calmly through a sunny valley while on the left settlers bring their cattle down a steep mountain road.

Julian Ashton’s A Waterhole on the Hawkesbury River (1885), painted in the year that Roberts returned to Australia, is a plein-air work made during a camping trip on the river in 1884. There is still a certain romantic sensibility, but more akin to Buvelot than to Von Guerard: above all there is a remarkable sensitivity to conditions of light. Ashton has captured that moment in the fading light of evening which anyone familiar with rivers will know, when reflections in the water seem clearer and more vivid than the world itself.

Next to this is a small but charming watercolour by the same artist, A Solitary ramble (1888); this picture was painted close to the middle of the day, as the short shadow indicates, but was also clearly a response to the heightened palette that Roberts and Streeton had by then developed.

Another work that shows the clear influence of Streeton is Sydney Long’s Midday (1896), a view of the Hawkesbury painted presumably after Streeton’s Purple noon but in the same year. The composition, however, is much more indebted to Streeton’s Cremorne pastoral of the previous year (1895), although Long’s palette is quieter and moodier, much less high-key than Streeton’s.

Long was away in England from 1910, but after his permanent return in 1925 he painted several more pictures around the Hawkesbury and the Macdonald rivers: Hawkesbury landscape (c. 1925), Reflection, Macdonald River and Spring, St Albans, both around 1926. All three of these are plein-air works and close inspection tells much – or in some cases raises interesting questions – about his procedure, including the use of coloured grounds. In the last of these pictures, for example, we can clearly see the care he took with things that had to be got right while he was in front of the motif, like the structure of the cabin, and the casualness with which he has brushed in the background.

There are many other interesting works, including three fine wood engravings and a number of prints by Ure Smith, a talented etcher as well as an important publisher. There is an evocative, rather gloomy landscape by Desiderius Orban, the famous teacher who had immigrated from Hungary (1943), and a beautiful little picture of a barn by Lloyd Rees, which is a study in the tone, temperature and mood of light: the dawn sun striking the top of the barn is actually brighter than the sky, not yet filled with the reflected light of the sun, and lower outbuildings are still shrouded in darkness.

The later period is, however, dominated by Elioth Gruner, whose famous Spring Frost (1919), one of the most popular paintings in the Art Gallery of NSW, is in a sense the centrepiece of the whole exhibition.

It is preceded by two smaller works, Summer morning (1916), in which a young harvester stands holding an armful of some freshly-cut crop – perhaps hay but not wheat, since it is still green. He is seen in contre-jour, so that we cannot see his face: he is an anonymous and generic figure, not a portrait. The other is Morning light (1916), which won the Wynne landscape prize in the same year; it is unfortunately hard to imagine so simple and unpretentious picture being successful today.

Spring frost itself represents the same farm as Morning light, but seen from much closer now, and on a bigger and more imposing scale. Again it is dawn, but now in winter; the light is brilliant but cold, as the title of the picture and the frost on the grass in the foreground tell us. But there is more to this picture than remarkable observation of natural phenomena.

The prominence of light in the composition, heightened by the unusual placement of the darkest area of the picture in the middle, inevitably suggests spiritual connotations. And there are two different manifestations of light: the immaterial radiance of the sky, and the more earthly, material form of light which is manifested as it strikes objects, like the cows and the fences, and casts shadows on the grass.

And thus the things represented in the painting, ostensibly its subjects – the cows, the farmer himself hidden in the shadows – are no more than occasions for the manifestation of light, the visible form of a pantheistic energy pervading and animating the natural world.

Fieldwork, Hawkesbury Regional Gallery, until September 20.

-

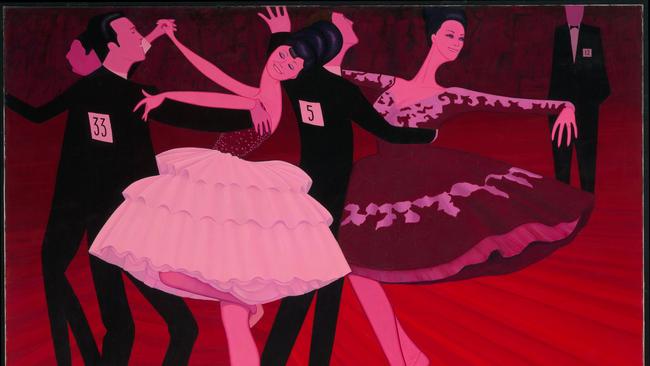

During the 1960s John Brack became captivated by professional ballroom dancing. He attended the World Ballroom Dancing Championships at Melbourne’s Festival Hall in 1967. He collected copious photographs of ballroom dancers, fashionable hairstyles and clothes. He even subscribed to The Australasian Dancing Times magazine.

This was all part of Brack’s meticulous research to give authenticity to a new series of works he was planning on ballroom dancing. He was attracted to the subject because, he said, he was interested in how the joyous activity of dancing had been turned into such a demanding and challenging ritual.

Just prior to embarking on the ballroom dancing series, there had been a major shift in Brack’s career. He’d given up his full-time job as head of Melbourne’s National Gallery art school so he could concentrate on painting. The ballroom dancing paintings were his first as a full-time professional painter. They were first exhibited in 1970 but the show didn’t sell very well, and it wasn’t considered a success. Most of the critics thought the paintings were absurd and the colours jarring. Brack, however, thought the series was his best, even better than his renowned Collins Street picture of office workers. And perhaps to prove his point, the ballroom series now fetches among the highest prices for his work.

One of the major paintings of the series, Latin American Grand Final, 1969, is in the collection of the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. The composition of neon pinks, reds and black, captures the lissom dancers in their richly decorated dresses and high-heeled shoes. It also includes a self-portrait of the artist dancing alone in the left-hand corner.

At the NGA, the assistant curator of Australian painting and sculpture, Lara Nicholls, says that Brack used dance as a metaphor – the dance of life. “In essence, the painting is about false intimacy and false joy. Here is this scenario which is ostensibly quite romantic, a man and a woman dancing to music, but it is a competition where you must maintain this veneer of fun and joy, but it is quite anxiety inducing because they are in fact performing to a set of rules and everything is so scrutinised by the judge, who you see looming in the right hand corner.”

Latin American Grand Final was the first time Brack had worked on such a large scale and it was a breakthrough moment for him, Nicholls says. “I find Brack is so masterful at being able to delve into the human condition and human nature. In this work, he was like a private investigator taking his vivisector gaze to the competitive world of ballroom dancing. And what I love about this work is the boldness of it. He has this confidence and I really love that. This is a brave, brave painting. I think it shows the gloss and the darkness of life.”

Materials: oil on canvas. Dimensions: 167.5 x 205cm

Bronwyn Watson

-

SALEROOM

Hugh Sawrey was largely a self-taught artist who first started drawing using the charcoal from campfires while he was working as a drover in outback Queensland. During the 1960s he decided to become a full-time artist and took lessons in Brisbane with Jon Molvig and Caroline Barker. Sawrey, who had a long career, was keen on depicting Australian scenes, such as droving, and was known for his love of the bush poets. When he became financially successful, he founded the Australian Stockman’s Hall of Fame at Longreach, Queensland. Two of Sawrey’s paintings were among the top sales at a recent Australian and historical auction by Leski Auctions. Sawrey’s McConachies Ten Horse Team North Queensland sold for $17,925 (including buyer’s premium), while Trooper On Patrol, Ranken NT also sold for $17,925. The top sale was an early 19th-century Anglo-Indian centre table carved in solid padauk that sold for $19,120. Leski’s joint managing director, Harry Glenn, told Saleroom the auction achieved some “excellent results across the board”. “We had 650 participants who purchased over 80 per cent of the lots on offer over the two-day auction,” he said.

Bronwyn Watson

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout