The art and guilt of self-hatred

Cultural edginess has been replaced with self-pity about our ‘vulnerabilities’ and our supposed need for ‘healing’.

It says a lot about this year’s Asia-Pacific Triennial – the 11th in the series – that the most memorable work in the exhibition is a piece reprised from the inaugural APT in 1993. Shigeo Toya’s Wood III (1991-92) is one of the first things you see on entering the Queensland Art Gallery building, or at least the first serious thing you encounter. It takes the form of a collection of wooden posts that were once square-cut beams but have been ingeniously carved with a chainsaw into a bewildering variety of forms.

The most poetic aspect of this work is the way that original beam, whose squared and planed blockiness is still visible at the base, has been transformed from industrial uniformity and sterility into a plethora of organic and dynamic shapes; some seem to have the animation of flames, others suggest the encrustations of shells or coral, or again the morphology of plants or flowers. The underlying idea is simple enough, but the evocativeness arises from the unexpected diversity of inspiration and the skill of execution.

Toya’s work has been set in a room surrounded by other things that are meant to establish a dialogue with it, but they all look bland in comparison. And bland is generally the tone of this exhibition, perhaps not surprisingly when a wall panel welcoming visitors to the Triennial informs us that “…the exhibition delves into how artists acknowledge vulnerabilities and create time and space for healing and care of culture, community, heritage, land and one another”.

Is this what our culture has come to? This valetudinarian self-pity about our “vulnerabilities” and our supposed need for “healing”? What about boldness, courage, the spirit of adventure? Presumably those qualities are now felt to be too masculine, too implicated in power and self-assertion and empire-building. And no doubt the culture of modernism in art was suffused with a macho rhetoric of boldness, innovation and experimentation which still lives on in the tired formulas of press releases.

But the interesting thing today is that boldness, courage and the spirit of adventure – the same qualities that drove the age of scientific discovery as well as the generations of exploration that opened up the globe several centuries ago – are still alive in the world of technological innovation, and embodied in the men who today lead its most important corporations; undoubtedly remarkable individuals even if, like their predecessors, they’re also potentially buccaneers.

It is only in the institutions of culture, the arts, and parts of the modern university, that these values are repudiated in favour of a kind of defeatism, resentment and self-abasement which sees everyone as wounded (a Freudian might suggest castrated) and in need of “healing”, and attributes the cause of this implicit wounding to the composite and imaginary bogeyman of white patriarchal imperialism – or in other words the spread of European science and technology which has now transformed the modern world as we know it.

The guilt and self-hatred of sub-intellectual apparatchiks help to explain the drift of our cultural and academic institutions into increasing irrelevance, and their disconnection from the areas of contemporary society and industry that are as dynamic as ever. This is a matter of concern because as the cultural sphere becomes weak and ineffectual, it loses the ability to engage in a much-needed dialogue with the buccaneering leaders of the technological world. And there is no dialogue without some fundamental understanding, sympathy and sense of common purpose.

It is all too easy to forget that not only most tangible things we value in contemporary society, like modern medicine and our iPhones, but also everything intangible – democracy, free speech, universal human rights, the rights of women and minorities – all come from the western tradition. And in a world in which democracies, for all their failings, are ranged against such brutal and oppressive regimes as those of Russia, China and Iran, it is quite literally vitally important – a matter of life and death – to have confidence in our own values and assert them strongly in the face of our totalitarian opponents.

So what are we really left with in this exhibition which claims to be about “art that crosses borders”? There are rare examples of modernist or postmodernist works like those of the Japanese Ishu Han, both strangely awkward but somehow engaging videos of performances: in one “swimming” across a desert, in the other futilely hoeing the sea. The imagery has an edge of absurdism and desperation, but also a sense of determination in the face of absurdity that makes one think of Samuel Beckett.

Another video work, projected on several screens, is based on surveillance video cameras in Bombay which are programmed to tilt downwards from a skyline of new office buildings to a reality on the ground level of poor people scurrying around in more makeshift structures of corrugated iron and tarpaulins; the work is appropriately titled Bombay tilts down. Although the work is of some interest, it is hardly gripping and its deployment across various screens in a large space seems intended to distract us from the rather modest insight it offers.

There are more exhibits in what could be considered traditional media than are usually allowed into official surveys of contemporary art, reflecting a greater curatorial openness to the use of such media in third-world countries. The paintings of another Indian artist, Rithika Merchant, are a case in point: intriguing confections of occult symbolism, apparently of her own invention. A series of paintings by the Iranian artist Shahla Hosseiniis not unappealing, but seems almost shockingly insipid and non-committal considering the intensity of the social and cultural dramas playing out in her country at the moment, where the theocratic regime has been humiliated by the defeat of its terrorist proxies in Lebanon and Gaza and the catastrophic loss of its puppet Assad in Syria, and is simultaneously facing a crippling economic and energy crisis and the increasing refusal of women to submit to the oppressive dress codes of the mullahs.

Muhlis Lugis is a printmaker from the Philippines who makes very large woodblock images illustrating stories from the Bugis people of South Sulawesi in Indonesia, who converted to Islam in the early 17th century but many of whom still retain some beliefs from their previous animistic culture. In one large image, village youths oversee the mating of a horse and a mare, while the village chief looks on. In another, the goddess of rice and fertility – an animistic figure who seems to have had acquired some overlay of Indian associations – dies and is mystically transformed into the rice crop itself.

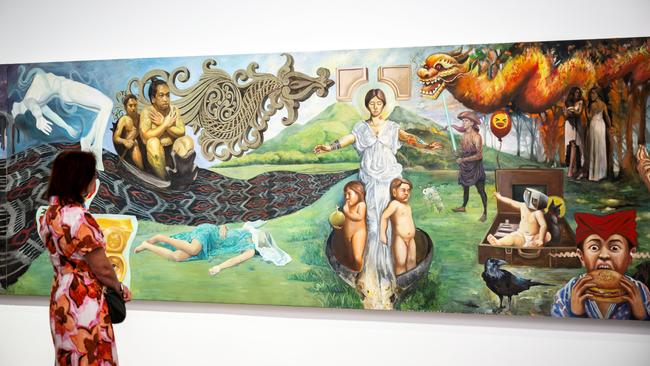

An enormous figurative panorama painted in oil on canvas by a collective called Piguras Davao, from Davao City on the island of Mindanao gives a vivid impression of the complex layers of culture that were present in The Philippines even before the centuries of Spanish and later American rule. Tribal peoples lived there for thousands of years, followed by more advanced Neolithic populations, and over subsequent centuries there was contact with the civilisation that spread from India down the Southeast Asian peninsula to Java, as well trade with China; Hindu and Buddhist beliefs merged with older animistic traditions. Then they were colonised by Moslems, and from the 16th century by the Spanish, who sold the whole colony to the US in 1898. The painting is crude and eclectic, but effective in conveying a similarly eclectic and perhaps never fully synthesised national culture.

The whole exhibition seems in fact to be increasingly turning from contemporary art to folklore; this is to some extent understandable when so much official contemporary art is so vapid, globalised and commodified – like the cutesy-clever but vacuous work of the Thai Kawita Vatanajyankur – but it runs the risk of falling into nostalgia and fantasies of primitivist authenticity, as we saw with the last Sydney Biennale.

The interest in folk art and craft traditions takes several forms in the present show. There are true folk traditions of craft, particularly in textile forms, like the Pis Siyabit weavings of the Tausug people in The Philippines. These pieces are examples of a traditional craft that is not trying to present itself in any sense as art. Then there are pieces made within a craft tradition but changed – notably in scale – to be presented in the context of an art exhibition; to this category belongs an impressive work from Uzbekistan made by Madina Kasimbaeva with a team of student assistants. It is a Palak suzani (“suzan” means needle in Persian, and Uzbekistan, like other central Asian regions, was part of the greater Persian cultural sphere), an elaborate work of embroidery that a mother would patiently make over the years as part of her daughter’s future dowry.

From Timor too comes a collection of wood-carvings that represent an old folk tradition but are now poised between ancient animistic fetish and modern tourist souvenir. Nearby is another set of Timorese works based on the elaborate carved doors made for huts meant to house the spirits of ancestors in the old animistic traditions. The huts have no windows and the doors are no doubt especially important to confine the spirits and prevent them from haunting the living. Here the artist has carved new sets of these traditional doors as art works, blackened with soot to give them the aged appearance that a foreign collector will value. As with much indigenous art in Australia, the trouble with such work is that it derives its interest from beliefs and practices that are disappearing among the original populations, and that it is addressed to an outside market seeking exotic products and the last vital expressions of fading cultures.

Yet another approach to folk traditions is represented by the Saudi artist Dana Awartani who – very far from such village craftsmen – is evidently wealthy, was educated in London and now lives between Jeddah in Saudi Arabia and New York City, from where she works, we are told, “in collaboration with artisans from South Asia and the Arab world”. In other words, the work that we actually see in the exhibition, with the exception of the drawings, has been sub-contracted to poor people with a real practice of craft.

The trouble with this kind of product is not only that the actual physical work, the craft and the making, are done by someone else. It’s also that once you have decided on the idea and the rationale, it can simply be repeated forever in various forms, accompanied by suitable would-be intellectual or spiritual commentary. It doesn’t require any real connection with the practice of making, or even any further thought; a perfect product to be hawked around the international exhibitions of the world, which are always in need of second-ranking artists to fill up their programs.

11th Asia-Pacific Triennial. QAGoMA to April 27.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout