Window into a lost artform

Whalemen who were bored out at sea scratched their longings into the teeth and bones of the great ocean mammals. Then one such mariner became tangled in a story of mutiny and misfortune.

“To do nothing at all is the most difficult thing in the world, the most difficult and the most intellectual,” Oscar Wilde once argued, suggesting idleness could be the mother of invention.

Few humans have walked in a loneliness more acute than the whalemen who crewed early commercial vessels in the 1700s and 1800s. Traversing the ocean for stints lasting up to five years at a time, riding on the roiling swell, whalers were driven to the limits of tedium, especially during long passages of “whale-sickness” when their quarry was scarce.

Between frenzied hunts, the crews – numbering 20 to 30 men, including harpooners, foremast hands, sailmakers, officers, shipwrights, carpenters, coopers and blacksmiths – needed to catch and process whales vastly outstripped the manpower required to run the ship. Out of boredom, idleness or sheer desperation, a strange form of folk art took hold among the whalemen.

Known variously as scrimshonting (as it was first recorded in the logbook of the American whaleboat Orion in 1821), scrimshoning, haberdashing or skrimshandering (as Herman Melville calls it in Moby-Dick), scrimshaw is the act of carving whale ivory, baleen and panbone. Primarily a way of eking out the hours, scrimshaw finds its closest cousins in whittling and whistling: activities where one can be said to be doing something while also doing next to nothing at all.

Into polished sperm whale’s teeth, baleen and whalebone – and, less commonly, dolphin and blackfish jaws, narwhal and walrus tusks – whalemen scratched their longings and visions: hallucinations of women with parasols, flowers, mythical creatures, patriotic motifs, palm trees, ornate buildings, valentines, effigies of Awilda the female pirate, fashion plates from magazines, knights, tattoo patterns and plants.

Australian scrimshanders also included Australiana, such as kangaroos, gum trees, emus and the coat of arms. Far from the shore, whalemen summoned up the world in fragments, from memory: images and icons, slim glimpses. They carved cathedrals, gods and goddesses into pearlescent enamel like prayers or offerings – an attempt, perhaps, to make the absent present. Poignantly, the most common scenes were of the only thing the whalemen could see and touch: whaling vessels and whales.

Like most rituals on sea voyages, scrimshaw was the object of intense superstitions. Some captains incentivised or even mandated scrimshaw-making on their vessels, believing it brought them luck. Others banned it, insisting it would curse the voyage. That scrimshaw was the subject of competing and contradictory beliefs is unsurprising, given the uncertainty of its origins. Rumoured to have been inspired by coconut-shell carvings across Oceania, or carvings of marine ivory in the Arctic, it emerged somewhere between continents, as if from the waves themselves. Practised by English, European, American and Australian whalers alike, it was given as a souvenir to loved ones, sold to collectors and bartered and traded at ports so frequently that most finished pieces are unable to be distinguished by their country of origin. Dreamlike, luminous and faintly macabre, embellished whale’s teeth crossed and recrossed the world, detritus of man’s hunt for leviathans, and evidence of a creature whose existence was mostly beyond imagination’s reach for those on shore. In these unlikely objects, the contours of human loneliness and of man’s brutality towards the natural world can both be traced, twinning.

Never does the human figure look smaller or more delicate than when etched into the tooth of a whale.

***

The history of Australian scrimshaw is also the history of scrimshanders’ families, who treasured and preserved the pieces in their possession – and like most family histories, it is necessarily partial and incomplete. Alfred Evans is one of the few Australian scrimshanders whose identity is known because, in donating his collection of 18 unsigned pieces to the Powerhouse Museum, his wife Sarah attested to his authorship. Evans was born in Southwark in London’s docklands around 1820 and by 1850 migrated to Sydney, where he found work as a cooper, and married Sarah the following year. They lived together at The Rocks.

For the next four or five years Evans worked for mariner and mercantile agent Robert Towns in his Millers Point warehouse, making barrels for Towns’s maritime empire, which transported commodities including Pacific whale oil, beche-de-mer and New Hebridean sandalwood, and indentured labourers from China and India. Towns’s attitude towards whaling was resolutely mercenary; his motto was “to Hades and back if there was a profit in it”.

On board whaling vessels, it was Evans’s duty to shape the staves of casks and barrels used to transport and store whale oil and reassemble barrels he had made on shore.

Little is known about his precise movements, but he joined several voyages between 1855 and 1865, including a long voyage to San Cristobal on the barque Jane in 1851. Somewhere off the coast of Australia and the Solomons, on a 221-ton boat that carried up to 1200 barrels of sperm oil, Evans made a series of simple but beguiling scrimshaw pieces from whale teeth, each featuring a singular figure: there’s a lush palm tree with fine-lined fronds and stems of nuts that seems to float like a mirage over what could be ground or restless water; a woman with braided hair in a dark bodice and full-bodied skirt; a gentleman with sideburns in a courtly stance; a blindfolded horseman wearing a cape, who might be Alexander the Great; and the Greek goddess Artemis, daughter of Leto and Zeus, protector of the hunt and of wild animals, who stands in a half-curtsy, proffering an arrow in one hand and demurely holding her bow behind her back.

A few of these pieces remain in the family’s possession, including a joyful pair of teeth featuring a dancing Pierrette on one and a Harlequin in an argyle costume with a ruffled collar on the other.

In his carvings, Evans lavishes close attention on sartorial details: the woman wears a bracelet, and the man a waistcoat, bow tie and watch chain; Artemis is adorned with a delicate crescent moon coronet on her forehead. The fabric of their clothes billows and drapes; fine lines mark out their folds and shadows. Evans’s figures are gestural, mid-movement. The gentleman extends his right hand towards the ground, almost as if he is giving way to someone. The woman holds her arms up in a graceful stance, as though she’s admiring something in the distance. Evans’s figures look to the side, not towards the viewer; they are each preoccupied by something unseen, just out of the frame.

***

The voyage Evans took to San Cristobal on the whaling barque Jane was an unhappy one, culminating in the disappearance of five men and the prosecution of the ship’s captain for deliberately abandoning them. The facts of this incident were sharply contested in court, with witnesses disagreeing on whether the men had deserted the Jane or been stranded to die at the hands of hostile locals.

What’s known is this: the Jane departed from Sydney in April 1851 to the South Sea fishery with a crew of 30 men, including Evans as its cooper. By October 16, the Jane had reached San Cristobal, where it stopped for wood and water. A week later, the Jane had the supplies it needed and Captain Brazier gave the barque’s crew 24 hours of shore leave so the men could wash their clothes in a local waterhole. Most of the crew had returned to the boat for dinner at 1.30pm or a little later in the afternoon.

By dusk, the captain sent a boat to shore for the remaining men but only three returned. Whether by design or by accident, five of the Jane’s crew – John King, George Miller, Samuel Setter, Alexander Smith and Stephen Watts – were left overnight on the island. The next day there was still no sign of the lost men and Captain Brazier ordered the Jane to lift its anchor and stand at sea. When challenged about why he wasn’t making a greater effort to find the men and asked how he could leave them “to the mercy of the islanders”, Brazier took a boat to shore with his second officer, navigator and four local boys. The boat was gone for 2½ hours.

No witnesses could say whether it had actually landed. When Captain Brazier returned, George Russell – who had been manning the ship’s wheel – overheard him say: “They will all be dead men in a month, and a good job too, the bastards.”

In Brazier’s trial, Russell testified that Captain Brazier ordered the Jane should set sail on a course for the south of the island, where the boat idled for three more days. He made no effort to find the missing men – neither lowering a boat nor dropping anchor for the entire three days – and swiftly replaced them with seven locals who joined the boat from their canoes. After this incident, Russell and two other crew members mutinied. They refused to continue whaling and were put into irons.

The Jane didn’t touch land again until December, when it reached Port Jackson, at which point Captain Brazier had the three men thrown into Darlinghurst Gaol and committed to trial for conspiring to break up the voyage.

Russell’s fellow informants, James Hudson and Thomas Morgan, mostly agreed with Russell’s testimony, but Russell’s account was later called into question because he failed to disclose that he’d had a serious altercation with Captain Brazier a few months earlier, when he had threatened legal proceedings against him, and was subsequently severely beaten and punished by being forced to make sennit – a plaited cord – for a fortnight on the ship’s deck.

The Jane’s chief officer, Joseph Woods, offered a differing account of the voyage. His memory was hazy, he claimed. He remembered the difficulty in coaxing the men back on board, and the captain saying, after the attempted rescue the following morning: “Those men will die of fever and ague, they are very foolish people so to leave the ship.” He also claimed a change of weather and a heavy current meant it was too dangerous to attempt rescue again.

The second officer testified that the weather had been “dirty” during the men’s shore leave and that Miller initially returned to the Jane at dinner time before returning to shore by insisting that his clothes were still drying on the island and then refusing to return to the ship. The second officer also testified that by the time the captain reached the island that evening the men had vanished and the coastal islanders reported they had gone to the mountains, where there were hostile tribes.

He claimed the captain had offered the coastal islanders two axes for each of the men – objects that were highly valued – and extracted a promise from the chief to look for them but who subsequently reported the men were beyond recovery, even when further rewards were offered.

The second officer testified that it was Russell and his fellow informants’ refusal to continue whaling that forced the Jane’s return to Sydney. The ship-keeper and navigator, Charles Wentworth, testified that the men had deliberately deserted and were prepared “to take up their abode in the island”. Evans corroborated this account and the magistrate dismissed the charges. The five men left on San Cristobal were never found.

Somewhere on this calamitous voyage – before or after the disappearance of the five men, and the subsequent mutiny of three more – Evans was etching his microscopically fine, controlled lines into sperm whales’ teeth.

***

During stints on shore, between whaling voyages or possibly later in his life when he was working as a farmer and living along Gladstone’s Macleay River, Evans returned to making scrimshaw, fabricating much more complex objects from whalebone and ivory than the carvings he completed at sea.

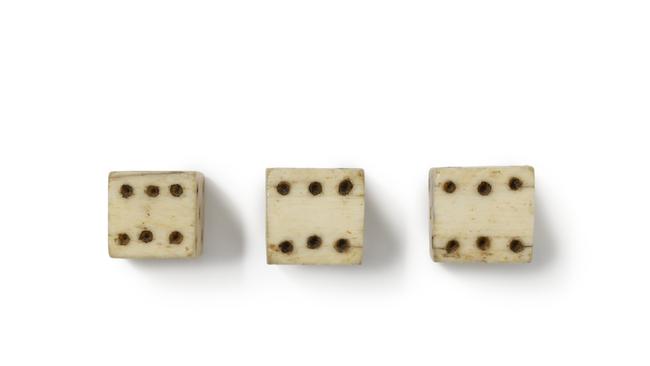

These elaborate objects included a salt and pepper cruet set, dice, a sewing needle case, an awl, as well as an intricate pocket watch stand and – in a subtle echo of Ahab’s ivory leg – a carved bone walking stick with a knotted handle inlaid with triangles, diamonds and circles of black and red tortoiseshell. If the pieces were completed later in life, it’s hard not to speculate whether these works were inflected with some nostalgia for a world Evans had left behind and was swiftly fading. Evans died in 1895, on the threshold of a new century that would usher in new sources of fuel that would make sperm whale oil and spermaceti obsolete, stark realisations about the ecological consequences of overhunting and overfishing, new ways of thinking about animal agency and intelligence, and new understandings of the interdependence between species.

In one light, scrimshaw is an act of mastery over the animal world, commodifying the whale’s remains as trophies or trinkets. Some might even see it as a defacement, or act of cruelty – the relic of a vanished world, as worthy of condemnation as elephant ivory. In another light, the scrimshander’s artistry is an act of homage or even subservience – a recognition of the whale’s miraculous vastness, and the impossibility of holding its totality in the human grasp.

This is an edited extract from Art, Idleness and Leviathans: Alfred Evans’ Scrimshaw, an essay commissioned by the Powerhouse for the Writing Objects series.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout