Door charge is the least of MCA’s worries as exhibitions miss mark

Free entry to the great museums of the world allows truly democratic access to some of the most important art and archaeology of the world. Has the MCA doomed itself to failure?

The Museum of Contemporary Art presented what were probably the best contemporary art exhibitions in Australia in 2024, including Tacita Dean and Hiroshi Sugimoto, and yet it finished the year with a couple that are somewhat disappointing, one more so than the other. Equally unfortunate was the news that the MCA will be compelled by budget constraints to start charging for general entry. Whether this will really improve its financial position remains to be seen: will enough people be willing to pay to visit the permanent collection?

Beyond this purely financial concern, however, there is a matter of principle, one of the most important we inherited from the British tradition of museums and galleries. Free entry to the great museums of London allows truly democratic access to some of the most important art and archaeology of the world, while also making it much easier to make frequent short visits, and to spend time with one or two works on each occasion, rather than feeling, as in many other museums, that one has to take the opportunity to look at everything.

Governments should consider it a duty and a priority to support free general admission to museums. This is a far better use of state funding than paying for ill-conceived capital works, such as the Sydney Modern extension or the catastrophic Powerhouse move to Parramatta, or – directly or indirectly – supporting dubious acquisitions like those recently made by so many national and state institutions.

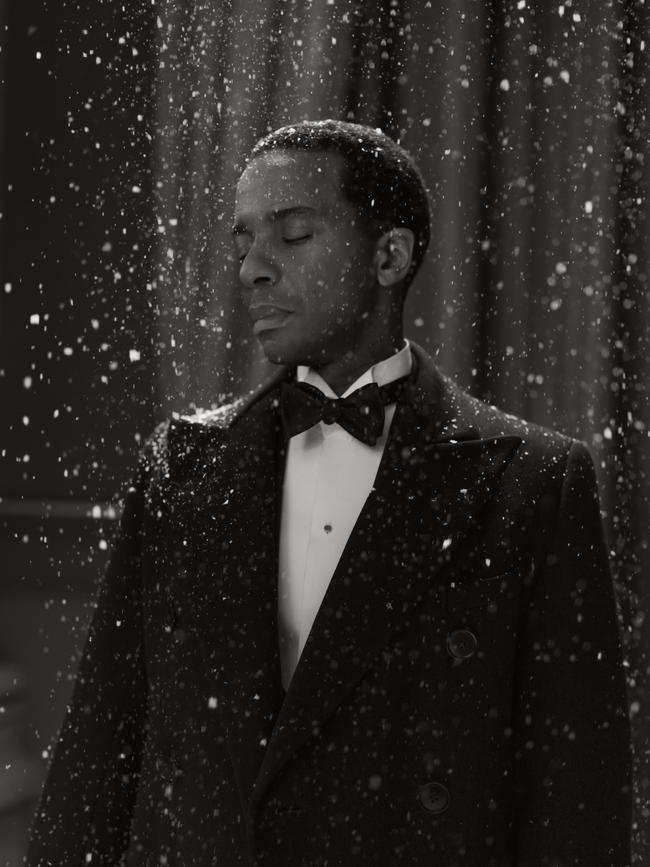

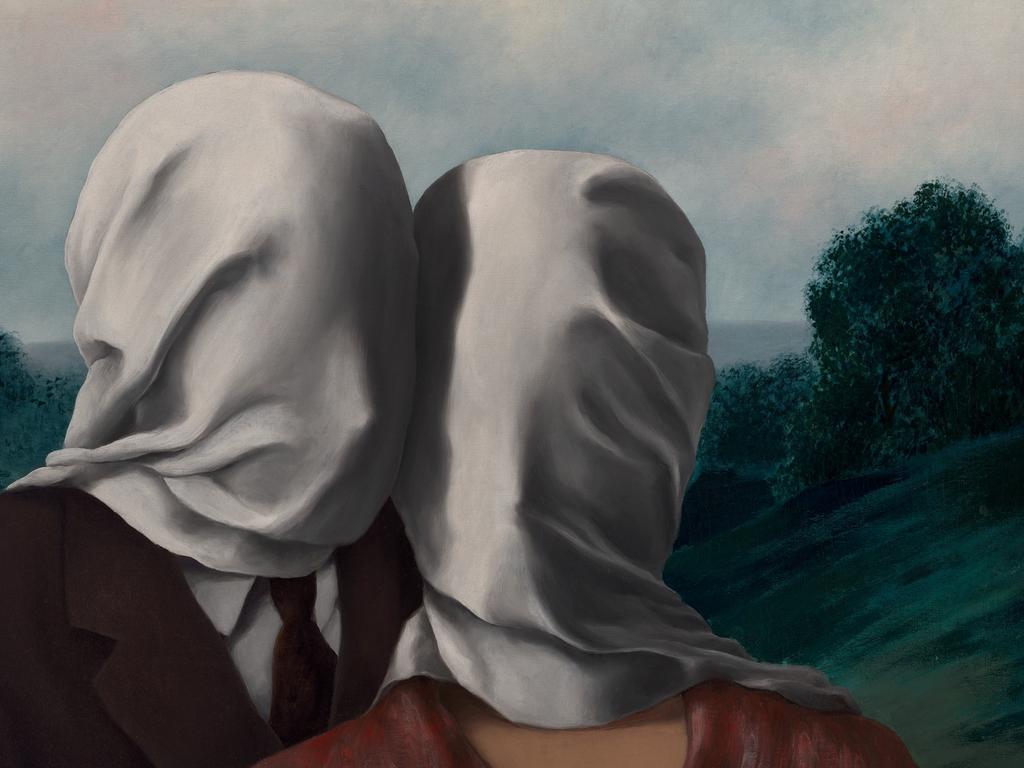

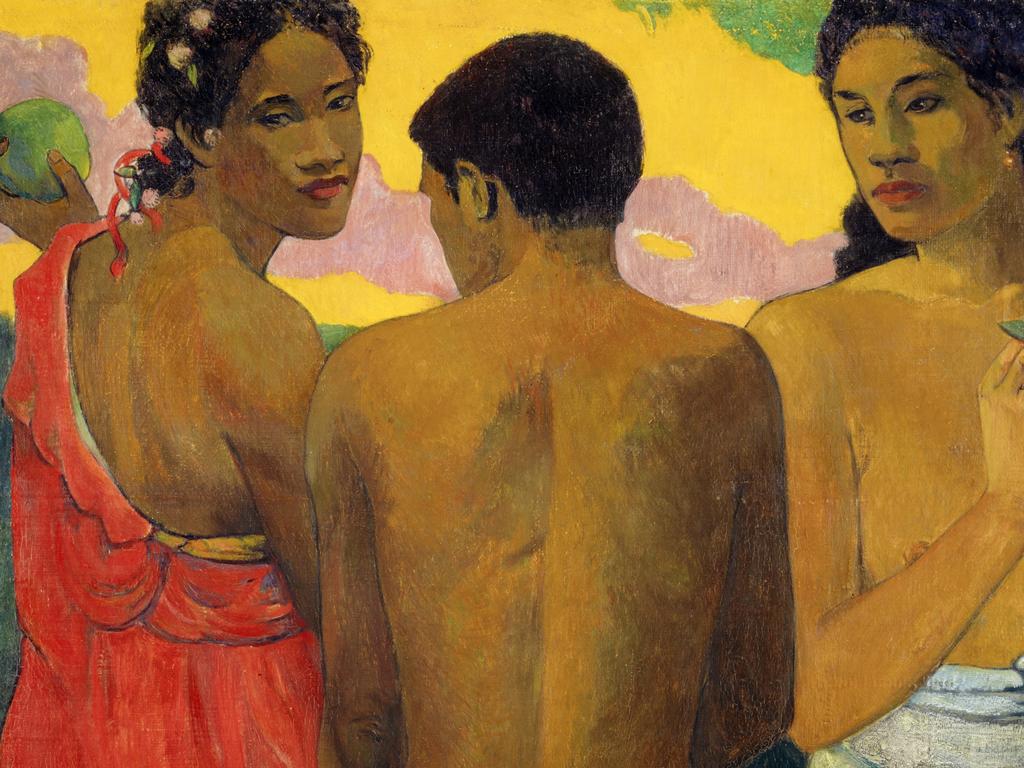

As for the two current exhibitions, one is on the entrance level: a large video installation by British artist Isaac Julien. The whole room is filled with screens on which several black-and-white projections run concurrently, while the walls are covered in a mirrored surface producing the effect of a maze of reflections. Around the walls, in display cases, are examples of African tribal sculpture borrowed from the Australian Museum.

The central conceit of the work is to imagine a kind of conversation between Dr Alfred C. Barnes (1872-1951), founder of the Barnes Collection in Philadelphia, and Alain Locke (1885-1954), the first black American Rhodes Scholar, who wrote about the appreciation of traditional African art. We learn this from the accompanying wall text, but otherwise what we witness is a conversation between an older white man in a mid-century three-piece suit and a younger black man who is something of an aesthete.

The narrative starts with shots of the outside of the Barnes Foundation in the snow – the original building from 1925, in which Barnes had stipulated in his will that all displays should continue to be shown exactly as he had left them until, after a legal battle at the start of this century, his will was overturned and the collection moved to its current premises. After this there are interior shots in the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, including several statues of famous scientists of the past.

The young protagonist, carrying a cane, walks around various anthropological displays musing over the ways African tribalart can be considered, then engages in a virtual conversation – the interlocutors are on separate screens, presumably drawn from their respective writings, again about ways of looking at African tribal objects and their claim to be considered as a serious art form within their own socio-historical context.

The trouble with this discussion is first of all that the arguments are pretty much uncontroversial and generally accepted today, and secondly that the two men seem to be in constant agreement, which means the discussion lacks dialectical engagement. It becomes like one of those exchanges we see on social media where everyone is eager to agree with their friends.

This mock conversation is all rather arch and self-conscious. This quality becomes even more pointed in scenes with a black American sculptor who, as we learn from the label, is meant to be Richmond Barthé (1901-89), seen working in a modern classical idiom from a naked and athletic black model. And had we not already drifted sufficiently into erotic reveries of black Adonises, there are glimpses of homosexual passion, a subplot that leaves us wondering where all this is going.

Upstairs is a ticketed exhibition by Julie Mehretu, an American artist of Ethiopian background, who was enthusiastically described by The New York Times a couple of years ago as “a rare example of a contemporary black female painter who has already entered the canon”. This is a textbook example of the way art criticism has been corrupted by marketing and the post-truth conviction that reality can be whatever you assert it to be.

The exhibition comes with the ambitious, or perhaps simply unintelligible title, “Julie Mehretu: A Transcore of the Radical Imaginary”. According to the MCA website, she is “one of today’s most acclaimed living painters”, and her exhibition demonstrates her “commitment to painting as a contemporary art form” and “her ongoing engagement with abstraction as a richly layered language, informed by histories of art and mark-making across millennia, from Chinese ink painting and Japanese manga to rock art, literature and music”.

If that sounds incoherent, it is – from equating art and “mark-making” to the slippery use of the plural “histories”, the confused sense of chronology and the pairing of Chinese ink-painting with Manga comic books. But the real clue is no doubt the reference to painting as a contemporary art form. Plenty of people practise painting today, in different styles and idioms, but almost none of them gets into the official surveys of so-called contemporary art put on by our state galleries, whose curators are evidently terrified of showing anything that might be considered “traditional”, unless of course it is a form of “tribal art”, which is granted a special exemption.

The art of painting, from past centuries to recent times – with Cézanne, Picasso, even Pollock – invites close attention and intimate engagement. Audiences today, distracted and jaded by the constant assaults of the mass media and digital environments, seem less capable of this sort of attention, and the work typically shown in biennale-type exhibitions is designed for this new audience: it is often of enormous, sometimes overwhelming dimensions to make an immediate and almost physical impression on viewers as they wander by, or else it is animated, moving, even hyperactive, addressing people accustomed to restless overstimulation.

Mehretu appears, consciously or unconsciously, to have set out to make a kind of painting that could hold its own in such an environment, where the variety of works and styles makes it even harder for viewers to look carefully at any single thing. First of all, of course, her works are enormous, which today almost goes without saying. And then they are produced with an invariable formula that imparts a superficial impression of movement, energy and complexity, and has obviously convinced many critics and even more art dealers.

Some of her work is on opaque surfaces, some on translucent screens. Her technical originality consists in building up the surfaces in depth using processes not usually found in painting, although none is without precedent, especially in other forms such as printmaking and poster design: backgrounds are either spray-painted or screen-printed; further patterns and shapes are produced by stencils; final graphic marks, sometimes recalling the gestures of traditional abstract painting and sometimes suggesting graffiti, are produced with airbrush or spray paint.

The result is indeed a series of very large works that make an immediate impact even on the passing viewer; but the trouble is that they give no more than that. My first impression on entering a room full of these loud and overbearing confections was of their breathtaking weakness. Closer inspection revealed how Mehretu’s effects were produced, but it did nothing to compensate for the aesthetic futility of her huge painted surfaces. The claim made for her work seems to be that she has renewed the art of abstraction, which has been in the doldrums for half a century, by employing different and non-canonical media and techniques. And no doubt many will enjoy a frisson of transgression in discovering media associated with graffiti in what purports to be a work of high art.

The text on the MCA website confirms the argument that the work is essentially about making an immediate and almost physical impact: “Blurring distinctions between abstraction and figuration, Mehretu’s paintings have a unique ability to inhabit the moment. To experience them in person is nothing short of a visual and physical event.” Realising, however, that we usually expect art to be something a bit more than “a visual and physical event”, the MCA makes a bolder claim: “Her work speaks to the power of art to express the dynamic and intersecting movements of history, people and cultures that shape our understanding of the world.”

It would take a great deal of imagination to see “movements of history” expressed in Mehretu’s work, except perhaps in a post-historical perspective in which a “dynamic and intersecting” cacophony of forms, fragments and traces is all that is left of millennia of human civilisations and cultures. But the truth is that beyond the gimmicky use of a variety of disparate media, these works are not even aesthetically innovative: in their treatment of figure and ground, movement, colour and form, they area pastiche of abstract idioms from Kandinsky to Pollock.

The works on paper are similarly repetitious and reveal the same compulsive and mechanical emptiness. As for the large paintings, they are little more than lush decorative surfaces, free of content and thus open to the projection of whatever meaning you like – the histories and cultures of the world, perhaps – perfectly suited for display in corporate foyers and the homes of the very rich: in fact in late 2023 one of her works sold for more than $US9m.

But even the very rich want to be assured that their status symbols are aesthetically significant, and so the exhibition is also accompanied by a hefty catalogue, full of illustrations and essays. Virtually all books published about living artists are marketing exercises, of course, as well as many recently dead ones, since collectors want to maintain the value of their assets. But the case of Julie Mehretu really looks like the last gasp of an exhausted New York art market desperately trying to whip up excitement for weak and vacuous art commodities.

Isaac Julien: Once again … (Statues never die) (MCA to 16 February)

Julie Mehretu: Transcore of the radical imaginary (MCA to 27 April)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout