The best and worst of art exhibitions in 2024

There were some welcome surprises on the exhibition calendar, mostly imports, but many metropolitan galleries had a lacklustre year.

As 2024 draws to an end, one of the last press releases to arrive from the Art Gallery of NSW spruiks a new book on its Sydney Modern extension; no doubt this architectural disaster will look like a triumph in a carefully curated collection of photographs. But I have yet to meet anyone who thinks it works as a building of any kind, let alone as an art gallery. The contrast with the highly successful solution to a similar hillside site at the Chau Chak Wing Museum at the University of Sydney is instructive and may suggest solutions for a future rebuilding of Sydney Modern. Meanwhile, of course, the new structure and the original gallery building have been given Aboriginal names that few people remember.

The reign of Michael Brand has come to an end, but we should see who is appointed before getting too excited; in the Australian gallery world it can always be worse. Just look at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra, which is responsible for two of the worst recent art purchases in the nation: $14m spent on Lindy Lee’s Ouroboros this year and $6.6m spent in 2019 commissioning Jordan Wolfson’s Body Sculpture, finally delivered in 2023.

The 2024 Biennale of Sydney marked a new low point for an exhibition that often has been underwhelming in recent years. The previous Biennale was somewhat better, but 2024 was of mediocre artistic quality and failed to make effective use of its new exhibition space in the old Power Station. One was left wondering whether the Biennale still served any useful purpose in the new millennium.

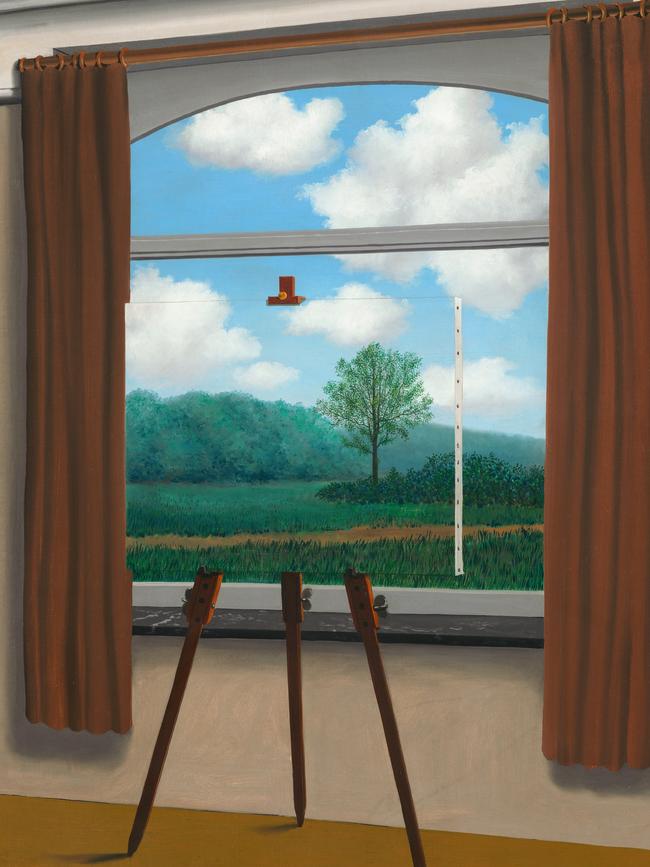

On a more positive note, in 2024 the AGNSW finally shook itself from its recent torpor, first with an intelligently curated retrospective of Lesley Dumbrell, then with the current survey of Rene Magritte. The Kandinsky and Mucha exhibitions were interesting but imported products. It is important for Australian galleries to foster the talent of local curators and scholars; whoever becomes the AGNSW’s new director should have three priorities before all others: extending the range and depth of its main collections; building curatorial and scholarly expertise; and fostering the development of the state’s regional galleries in the same way the NGV has fostered the outstanding regional gallery network in Victoria for more than a century.

The NGV itself has had a lacklustre year: much space and time was given over to fashion shows, which are simply cynical ways to boost attendance with people who are not really interested in art, as well as the appalling Melbourne Triennial, which showed the superficial and populist face of a kind of “contemporary art” designed for an audience of Instagram scrollers. The shameless dumbing-down this exhibition represented was emphasised by the concurrent run of an intelligent and scholarly exhibition about the sensibility of the baroque period, largely drawn from the NGV’s own collections but pointedly exiled to Hamilton in the Western District of Victoria.

One of the few exhibitions at the NGV that showed evidence of art-historical research and expertise was the joint survey of Grace Crowley and Ralph Balson. There was the impressive Pharaoh from the British Museum, but the NGV contributed little to this except for a rather over-designed visual and sound environment. And now the NGV is ending the year with one of the most overrated and commercial of contemporary artists, Yayoi Kusama.

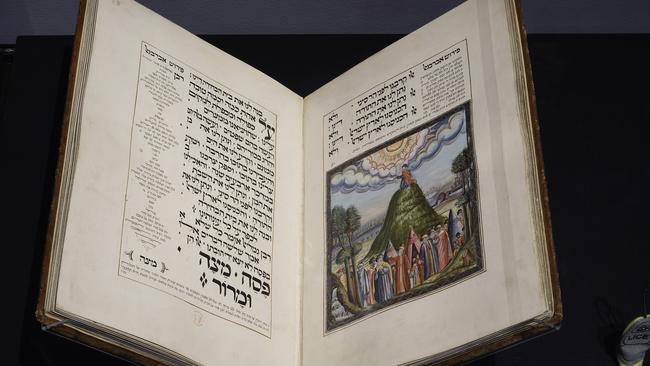

Elsewhere in Victoria things have been a bit more interesting, above all with Emerging from Darkness, already mentioned, at Hamilton. Luminous, an exhibition of Hebrew manuscripts at the State Library of Victoria, also was outstanding. Paris: Impressions of Life, at Bendigo Art Gallery, was an interesting selection of work from the Musee Carnavalet in Paris, and Heide Museum of Modern Art had a survey of the photographic work of Lee Miller. Geelong Gallery has presented several interesting print-based exhibitions, including Cutting Through Time, which considered the ways Margaret Preston and Cressida Campbell adapted the techniques of Japanese woodblock printing, while Castlemaine Art Museum’s Stonework revealed the more or less conscious responses to geological phenomena in the work of several Australian landscape artists.

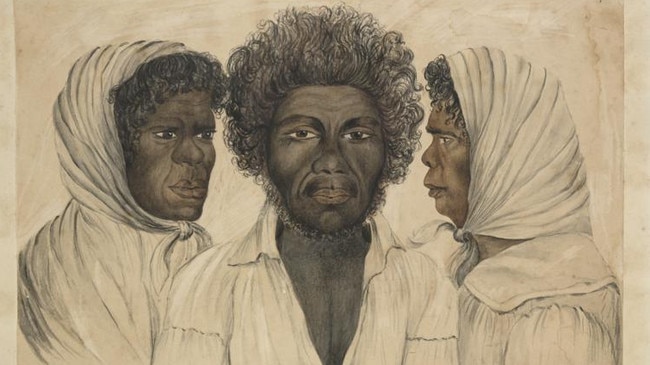

Among other institutions in Sydney, unfortunately we have lost the Museum of Sydney, which put on worthwhile exhibitions in recent years. We also have lost the Powerhouse Museum, another victim of political interference and incompetence by governments of both major parties. It is unclear when the Powerhouse will reopen and what its focus will be; it would be disappointing if it ended up being a museum of fashion. The State Library of NSW has continued to mount substantial exhibitions, almost entirely produced in-house, including the current Dunera (reviewed on October 26) and the earlier survey of a little-known but important colonial artist, Charles Rodius, curated by Australian art historian David Hansen, who sadly and unexpectedly died during the exhibition’s run.

The Australian Museum began the year with the spectacular Ramses, one of three ambitious Egyptological exhibitions in Australia, all following from the official bicentenary of the decipherment of hieroglyphic script by Jean-Francois Champollion in 1822, which was marked at the time by an important exhibition with this specific focus at the British Museum. The Australian Museum is closing the year with an exhibition devoted to Inca culture.

The Museum of Contemporary Art has also had quite a good year, starting with Tacita Dean and going on to Hiroshi Sugimoto, but is ending less convincingly with Isaac Julien and Julie Mehretu, whose work is like the last feeble gasp of an overhyped and exhausted New York art market.

The Art Gallery of South Australia has had a fairly weak year – one can’t expect too much from Biennale-type exhibitions – but produced a handsome book about its collection.

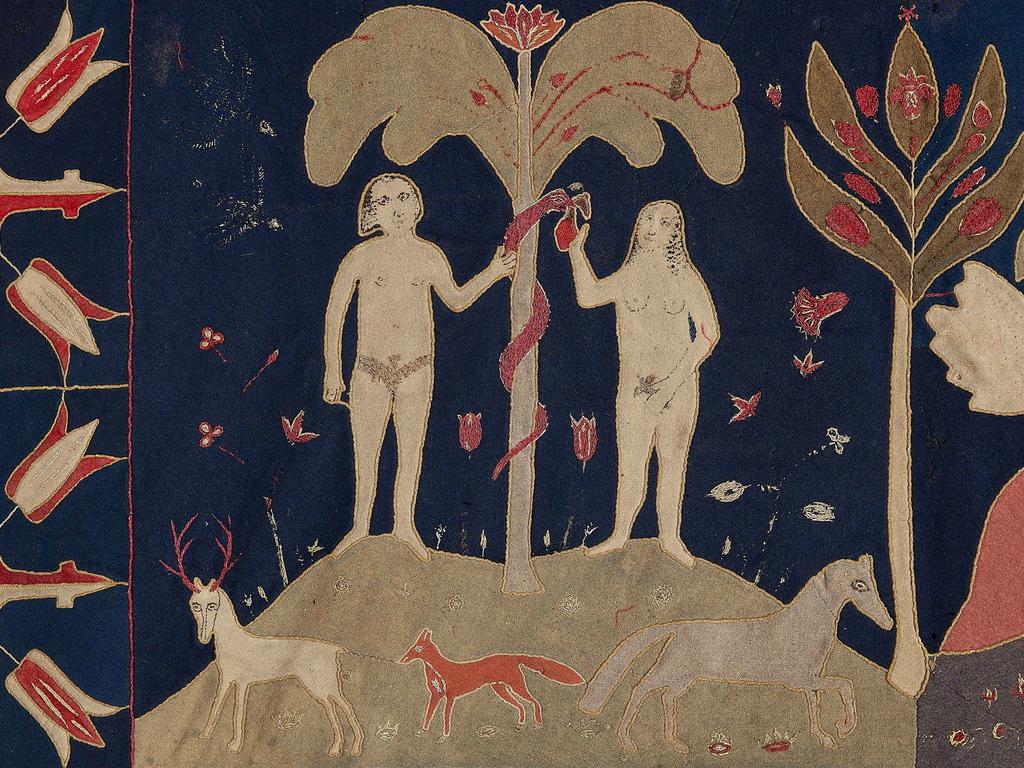

The South Australian Museum’s Waterhouse Natural Science Art Prize was a travesty this year, the first prize being awarded to work making tendentious claims about Indigenous languages and colonialism. Fortunately some smaller galleries in Adelaide did better, including Carrick Hill with The Hayward Nudes, a small but interesting exhibition, and the David Roche Foundation House Museum with two unusual and striking shows, one on the work of Wedgwood, revealing unexpected Australian connections, while Quilts: The Fabric of War displayed the little-known quilts made by soldiers from offcuts of military uniforms, especially in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Hobart had the usual eclectic range of exhibitions at the Museum of Old and New Art, beginning with Heavenly Beings, a collection of Byzantine icons first shown in Auckland, and Hrafntinna, an installation evoking the seismic forces at the heart of a volcano, and later the deliberately amorphous Namedropping as well as an installation inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy. At the same time, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery has offered more conventional but substantial exhibitions such as Lands of Light: Lloyd Rees and Tasmania.

In Brisbane, the Queensland Art Gallery presented the work of the little-known Isaac Walter Jenner earlier in the year, another modest but significant contribution to the history of painting in Australia. The Gallery of Modern Art’s more ambitious Fairy Tales was a mixed bag that began with a strong installation but lost its way after that. The gallery ended on a better note with the small but interesting pair of exhibitions Birds of Passage, devoted to Ian Fairweather and an artist who is probably unknown to most readers, Paul Jacoulet (reviewed in last Saturday’s paper), as well as the gallery’s most prominent regular exhibition, the Asia-Pacific Triennial, which will be discussed here in the coming weeks.

To return to Canberra, the NGA has managed to put on two notable exhibitions this year, both with visiting curators. The first of these was the survey of Emily Kngwarreye that was thoughtfully selected and allowed viewers to understand the different sets of work produced by the artist and to follow her development within each category.

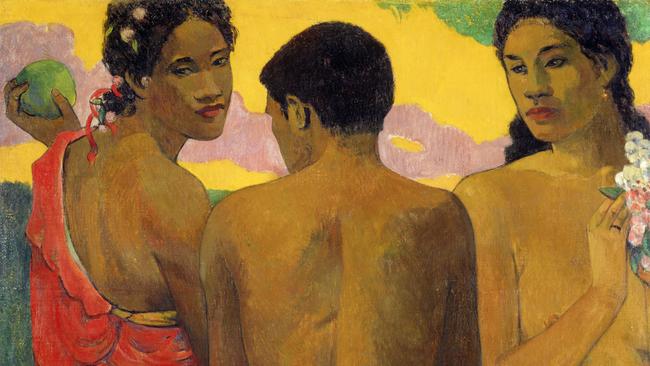

The other exhibition, perhaps the most important in Australia this year, was Gauguin’s world. It was a welcome surprise that the NGA, which seems to be obsessed with political correctness, would consider showing an artist who has become so controversial in their subculture.

The exhibition was as good as it was – and as free of moralistic commentary – because it was curated and directed by Henri Loyrette. Loyrette is the former curator of the Louvre in Paris and he was also responsible for Degas: A New Vision at the NGV in 2016, the best and most comprehensive exhibition of a modern artist I have seen in Australia. The NGA felt it necessary to produce ancillary material about colonialism and sex with young Polynesian girls (contrary to what is often implied, none of them was below the age of consent at the time), but fortunately no breast-beating was allowed inside the exhibition itself, on its labels or in the accompanying short film.

Elsewhere in Canberra, the National Portrait Gallery has had a rather ordinary year, and the institution seems to be increasingly affected by the same ideologies of gender, racialism and “decolonisation” as so many Australian institutions, but at least it is ending the year with a survey of photographer Carol Jerrems.

The National Library of Australia, which regularly mounts serious exhibitions from its holdings, has Hopes and Fears over summer, about the experience of migrants to this country. And the National Museum of Australia, which earlier had the third of the big Egyptian exhibitions, is finishing the year with one devoted to the city of Pompeii, where a city entombed by the eruption of Vesuvius still offers us a window into life almost 2000 years ago.

Best and worst of 2024

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout