Soldiers and sailors quilts attest to long, adventurous careers

Military quilts made by men in the 18th and 19th centuries, including soldiers and sailors, are the focus of an exhibition.

The craft of quilting has attracted quite a lot of attention in recent years, both because of the value of quilts as documents of social history and because they are usually made by women and thus represent the activity and the experience of a group that has been generally less prominent in many other fields of art and craftwork.

The present exhibition and its accompanying publication deal with another form of quiltmaking, which is much rarer and thus less well-known, namely quilts made by men, and in a military setting. These quilts are sometimes the work of soldiers and sailors, and sometimes of military tailors, in an age when armies regularly included specialist tailors, both to make the uniforms of officers, and to adjust those of the men, which were semi-industrially produced in a few standard sizes and probably regularly needed to be taken up or let out for particular individuals.

The first of many particularities of these military quilts is the special material of which they are made; it is military broadcloth, but those of us who are not textile specialists are unlikely to know exactly what this is. It is no surprise to learn that broadcloth is, in the first place, a heavy-duty woollen fabric; but it is then milled and beaten repeatedly until the fibres break down and amalgamate to become a kind of felt, although normal felt does not start as a woven fabric and presumably does not have the same structural strength.

One result of the felting process is that the fabric becomes very dense and largely water-resistant, and so strong that it offers at least some protection against shrapnel and other dangers. Because of this density and consistency, it can be left with raw edges that will not unravel and do not require hemming.

And this in turn is what makes broadcloth particularly suitable for the unique kind of intarsia work that we discover in this exhibition. Intarsia is a term more familiar in stonework and woodwork, as for example in tabletops that are composed of inlaid patterns of different timbers or of varied marbles or semiprecious stones. In each of these cases the timber or stone is cut out and assembled like a jigsaw puzzle, each piece abutting and snugly fitting alongside its neighbouring segment.

In more conventional quilts, pieces of fabric may be sewn together, but in that case an allowance has to be made for the seaming, which will be visible on the back; or they may involve patterns that are cut out and sewn onto a backing cloth in the “applique” process; or they may use embroidery – or indeed a combination of all three.

In intarsia quilts, on the other hand, the pattern is composed of elements cut out of broadcloth, directly abutting each other and then simply oversewn. The result is that the front and back of the work are in principle identical and the quilts reversible, except in cases when the maker has also added elements in applique or embroidery on the front, which is quite common in more elaborate or illustrative pieces.

The examples in this exhibition, mostly from the collection of Professor Annette Gero, who is also the author of the catalogue, are from the 18th and 19th centuries, in a period when military uniforms were still richly coloured; by the time of the Great War, almost all combat uniforms either already were or soon adopted the less conspicuous khaki (a Persian word that essentially means “earth-coloured”).

In earlier times, bright reds (from madder) and blue (from indigo) or green were common for breeches and coats, as well as other colours like yellow, white or red for lapels and cuffs, all serving to distinguish various regiments as well as ranks. Regimental tailors would have had quantities of the relevant fabrics on hand, and it was presumably from the many offcuts left over in the tailoring or fitting processes that most of these intarsia quilts were made, as well as perhaps from fabric salvaged and recycled from worn-out uniforms.

The craft of intarsia quilting is attested in central Asia from the third century AD and the exhibition includes a late Persian piece mimicking carpet design, but in modern times it seems to have its origins in the 18th-century Prussia of Frederick the Great; it arrived in Britain with refugees from the oppressive religious policies of the later King Friedrich Wilhelm III, who in 1830 attempted to enforce a union of the Lutheran and Calvinist churches. Many Germans migrated to Australia as well from this time onwards, mainly to South Australia and Queensland – making an important and often underestimated contribution to the evolution of the new nation – and some of these families brought military quilts with them, often made by family members during the Napoleonic Wars a generation or so earlier.

Accordingly, while most of the quilts here have British origins, the oldest ones are German or Central European. Three early ones from around 1760 illustrate Bible scenes, from both Old and New Testaments, and may have been used in churches to teach the sacred stories to illiterate parishioners. One shows Adam and Eve in Paradise – with a suitably tame lion – and then eating the apple and being expelled from the Garden. As in renaissance majolica, the narrative scenes are often borrowed from high art, and in this case the figures of Adam of Eve seem to be derived from a painting by Lucas Cranach.

A second quilt has far more complex themes, some less immediately recognisable to a modern audience: Elijah’s ascension to heaven in a flaming chariot, Abraham and the angels and Joseph being dropped into a well and sold to the Ishmaelites by his brothers, as well as Adam and Eve in Paradise and, from the New Testament, the Annunciation to the shepherds, the Adoration of the Magi and the Last Supper.

Another late 18th-century quilt from Bohemia is filled with detailed military scenes that relate to one or other of two mid-century sieges of Prague, as well as numerous vignettes of everyday life, including a marriage proposal and images of various professions and trades. There are also detailed and dramatic military scenes in “trapunto” – stuffed figures stitched on to the surface of the quilt – such as one in which a soldier has just shot and killed what looks like a turbaned Turk who falls from his horse while his pistol discharges in mid-air. The whole is framed by Adam and Eve eating the apple at the top and a skeletal allegory of Time with his scythe and hourglass at the bottom.

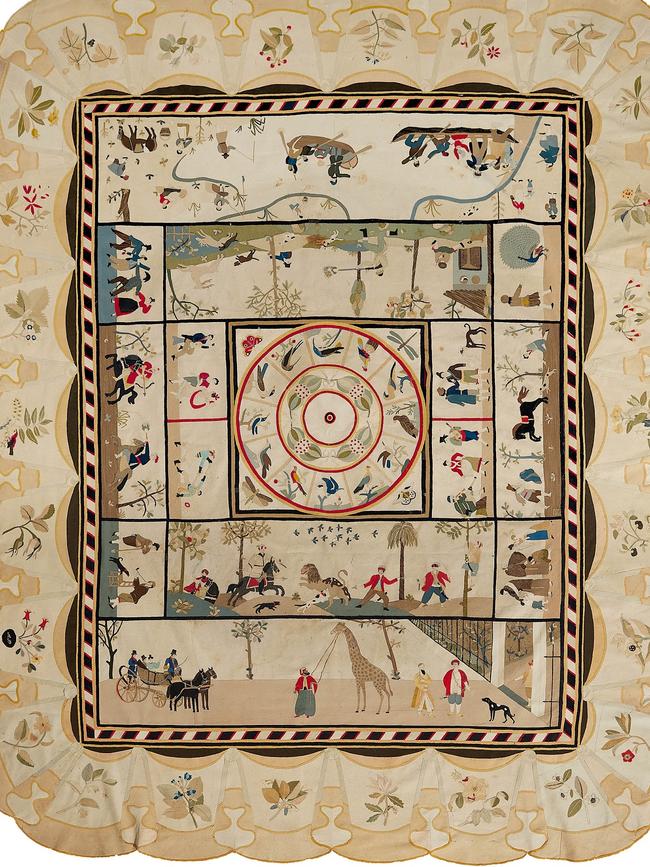

One of the earliest and most interesting English intarsia quilts is dated 1831. Its most striking vignette is of a giraffe, one of three, as we learn, sent by the ruler of Egypt to the Kings of England and France and the Emperor of Austria, apparently in an attempt to foster good relations and persuade them to stop supporting the struggle for Greek independence, which had by then been going on for a decade.

Of the three giraffes, the French one lived a good life at the Jardin des Plantes for 18 years; the one in London only survived for two, but like the others caused a sensation and attracted enormous interest. Each was sent with specialist handlers, whose exotic costumes are reproduced here, and the whole quilt is full of orientalist incidents, including a lion hunt and a confrontation between two mounted warriors in eastern costume, one firing a pistol and the other turning to shoot an arrow as he rides off, no doubt alluding to a tactic for which the Parthians had been famous in antiquity.

Later 19th-century illustrative quilts become more literal and less aesthetically interesting, like one that reproduces a group portrait of eminent military, scientific and literary men (c. 1870) and another, attributed to the same maker, which reproduces a print of Lord Palmerston addressing parliament while Disraeli, then leader of the opposition, listens. Both images are surrounded by elaborate floral designs. These productions have lost all the folk art charm of, for example, the 1850 Beleura quilt, which typically assembles a delightfully disparate set of figures and motifs, notably juxtaposing a scene of the death of General Wolfe following Benjamin West’s painting and another of the death of Lord Nelson, copied from a popular print, with a comparatively banal episode of rent collection from another contemporary Victorian painter.

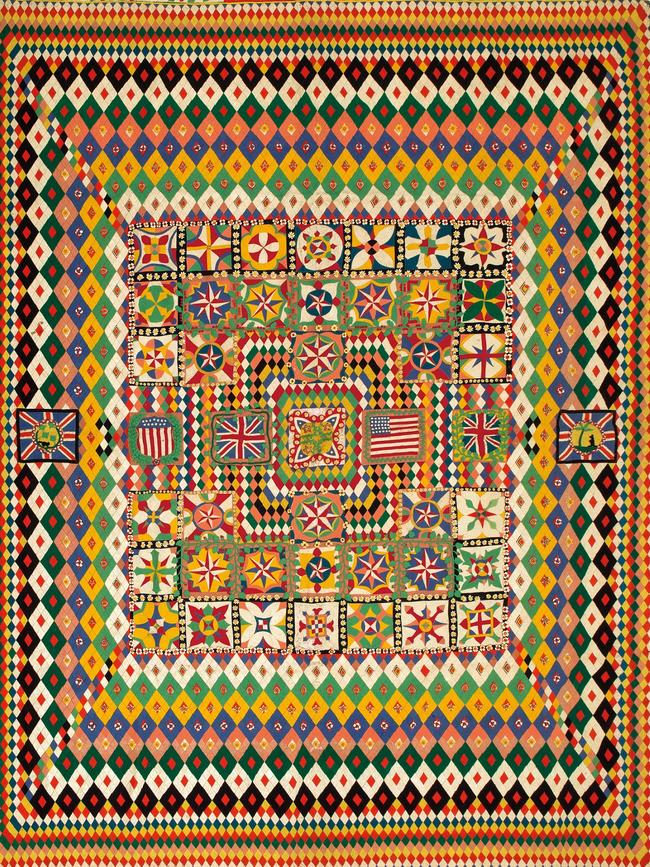

The folk quality is naturally most prominent in those quilts made by soldiers and sailors themselves; they tend to have fewer illustrative panels but more of the abstract geometric designs, especially patterns of squares and diamonds of different colours, that also frequently form the ornamental borders of narrative subjects. And whereas one can imagine the latter being planned as a series of scenes on a predetermined area, these highly geometric designs feel as though they must have been started from the middle and then extended progressively outwards in row after row of decorative motifs.

Sometimes these patterns are stupendously complex, and clearly took several years to produce. Some of them were executed during periods of internment as prisoners of war, while others were made in spare time while in barracks or at sea. The fabrics used often relate to the specific colours of the soldier’s regimental uniform, perhaps obtained from the regimental tailor as offcuts, as already mentioned, or cutting up old uniforms; one example of the former is the re-use of tiny circles of fabric left when punching out buttonholes.

These quilts were typically produced by soldiers and sailors who had long and adventurous careers as their ships or regiments were moved around the world from one conflict or garrison posting to another. Coats of arms, national and regimental flags and other details allude to their affiliations and to the campaigns in which they took part. Stylistic motifs reflect the influence of the cultures they have encountered in their travels.

Perhaps most suggestive in this sense is a Crimean patchwork by a soldier who had served in India, and which is clearly designed in the shape of a mandala, one of those ancient patterns found in Hindu and Buddhist art, in which squares, circles and crosses, bilaterally symmetrical, are superimposed or contained one inside the other.

This direct allusion to designs used in spiritual contemplation and meditation suggests a useful way of looking at many of these quilts, particularly the ones that are largely composed of complex geometrical patterns.

Regular patterns and symmetrical ornamentation are among the oldest expressions of the human aesthetic instinct, a fundamental way of asserting a human sense of order over chaos. The obsessive intensity of repeated geometrical patterns in many of these designs is no doubt directly proportional to the trauma, loneliness and suffering experienced in war by the men who made them.

Quilts: The Fabric of War

Roche Museum until May 18

Annette Gero: Quilts: The Fabric of War 1760-1900

Beagle Press, 2024

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout