The Torch art program: ‘When you’re painting country - you can feel like you’re not in jail’

Sean Miller cracked the art market back when he was in prison thanks to art program The Torch that got him his first NGV commission. Now the full-time artist is helping others see the light.

‘When you’re sitting in a cell, when you’re painting country, it takes you out of that environment. And you can feel like you’re not in jail. Art has a way of fixing your depression being inside a concrete jungle.”

Fifty-nine-year-old Gamilaroi artist Sean Miller is speaking about the four years he spent in Loddon Prison, near Castlemaine in Victoria.

In jail, he immersed himself in the ceramic class established by Uncle Jack Charles, the gifted actor who died in 2022. And as he sunk his fingers into clay to mould his works, Miller would see his ancestors shaping trees. Whenever he would paint in his cell he would daydream about being on country, the bright fluorescent light above replaced with the incandescent glow of the sun.

In 2011, Kent Morris, a Barkindji artist, from an art program called The Torch, visited the jail. He saw potential in Miller’s sculptures and gave him books about culture with images of country, totem animals and profiles on significant elders Miller would use to inform his pieces. Then something remarkable happened: Miller cracked the art world.

“Kent came to the art class and I didn’t really know what it meant to exhibit your work,” Miller recalls, over the phone to Review from Moree in northern New South Wales where he is visiting his family.“I had ceramics, and paintings – Kent said he would get them stretched.

“He came back in and told me that a curator from the National Gallery of Victoria wanted to commission me to do some pieces. I did a series, put a story to it and it ended up going into the Melbourne Now exhibition (in 2013). Now I’ve just a sold a work to the National Gallery of Australia.”

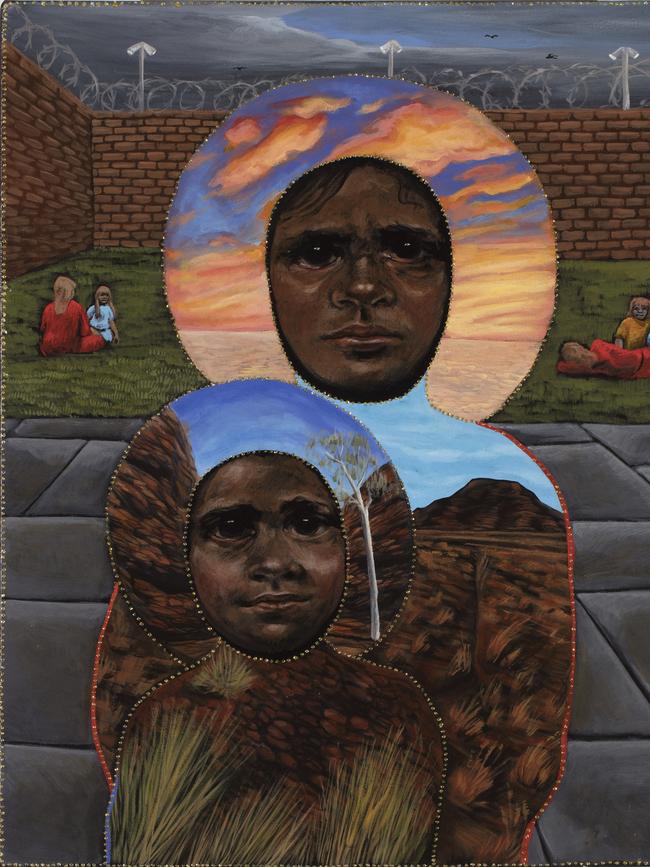

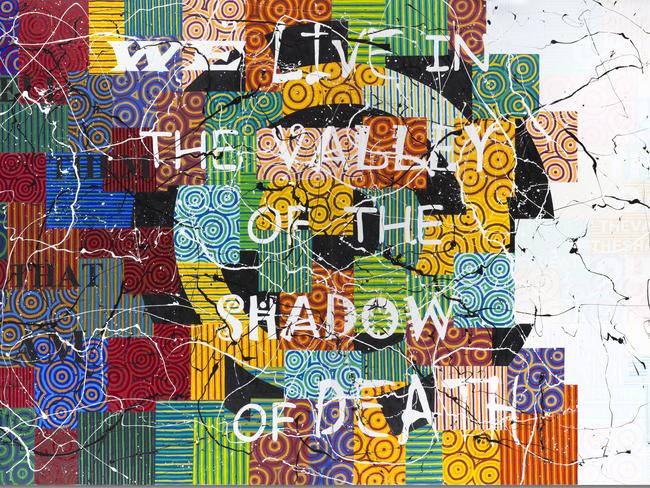

Now living in northern Melbourne, Miller is one of the artists showing in The Torch’s most significant exhibition to date. Held at Melbourne’s Heide Museum of Modern Art, Blak In-Justice: Incarceration and Resilience features the work of leading Indigenous artists such as Destiny Deacon, Richard Bell and Gordon Bennett alongside current and former inmates who have been through The Torch’s art program. The Torch creative director and curator Morris says the exhibition also “gives you a big slap in the face” with its awareness of shocking Indigenous incarceration rates.

“(It says) here’s one of the answers, here’s one of the solutions that has proven to be beneficial over decades,” Morris says. “But we’re just not listening.”

On April 2, three days before the exhibition opened, a 31-year-old Aboriginal man was found dead in his cell at Eastern Goldfields Regional Prison in Kalgoorlie-Boulder. He was one of 590 Indigenous people who have died in jail since the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody released its final report in 1991.

According to the latest Closing the Gap data, the crisis is worsening. The rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in jail has increased by 20 per cent since 2019.

Morris says programs such as The Torch can help. A 2019 evaluation of the program looked at the return-to-jail rate of 66 people who stayed connected with The Torch for at least 12 months after they left prison. It found that just 11 per cent had returned to jail, compared with a recidivism rate of 53 per cent for Indigenous people in Victoria.

More recent data from The Torch is similarly encouraging; 15 per cent of artists released from prison or in The Torch’s community program in 2020 returned to jail in 2021 (in Victoria, 39.5 per cent of prisoners released in 2020-21 returned to prison within two years).

Morris was eager to drive The Torch’s pilot back in 2011, after he had emerged from his own dark place and complex journey of rediscovering his Aboriginality.

Morris says he grew up knowing little about his father, who was born in Tibooburra in far northwest NSW and faced “extreme racism and discrimination”. When Morris was 11 his family took a roadtrip to Dubbo, where he met his paternal grandmother for the first time.

“This was our first interaction with our Aboriginal families. There was a large Aboriginal woman, and she gave me this hug, the world seemed to stop still. It wasn’t one of those happy reunions. We never saw them again. Dad never spoke about it on the way home.”

Through “the misuse of alcohol and other behaviours” Morris ended up before a magistrate when he was in his mid-20s.

“I think for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people not knowing family and not knowing identity, it can lead to expressions and behaviours and emotions,” he says. “And it can often end you up in front of a magistrate for no other reason than you just had a kind of transgenerational trauma handed down the line.”

A chance encounter led Morris to an exhibition put on by the Koori Heritage Trust. Here were the people who could help him find what he had lost.

“It seemed like the whole community came out and wrapped themselves around me to try to figure out what might be done with this fella because he’s not doing so good,” he says.

He connected with lost family members. He went “out bush” and made a didgeridoo. He painted up and danced in a corroboree.

When the job as Statewide Indigenous Arts Officer at The Torch came up he knew he would need to work sensitively.

“Uncle Sandy Atkinson, when he was still with us, said to me, ‘don’t take this job and build this 18-month pilot program, unless you can be 100 per cent sure you’ll turn it into an ongoing program’. We’ve had so many of these pilot programs, the community loses trust.”

Every time Morris visited a prison he would sit down and ask the inmates questions. What do you need while you are living in prison? What do you think will work when you go back to community? “Firstly, they said: ‘We don’t want to keep connected to the criminal legal system. We’re really not sure how to do that, but we know that creating art supports us and helps us in some way’,” Morris recalls.

“ ‘We want to have a cultural knowledge, a layer of who we are, where we’re from.’ The main question people raised, was: ‘How do I paint when I don’t know who I am or where I’m from?’

“The second one was: ‘How can we make some money? How can we improve our economic situation? How can we connect to an economy and to the arts economy?’.”

Inmates can learn “how to” make art through TAFE programs, but The Torch fits in at a foundational level and provides them with the cultural knowledge and support to explore community stories and identity in their work, and learn about exhibitions, sales and licensing.

First Nations researchers create books particular to an inmate’s language group including information about artists from community, bush tucker and country. Indigenous arts officers go into the prisons to talk through the books and discuss with inmates how they might develop or improve their art projects, as well as discuss the practical aspects of the art business.

When Morris started the program in 2011, he says, people were cynical about staying out of jail.

“People would say ‘see you soon, Ricky. I’ll keep your cell warm’.

“We have seen that just vanish. Now people in the program say ‘good luck, brother or sister, see if you can get a job with The Torch’. You’ll be right.”

Back in 2011 the pilot had 80 participants. Today The Torch is in 15 Victorian prisons and works with about 800 artists who are current or former inmates. It employs 27 people, many of whom went through the program inside. Miller has worked as an Indigenous arts officer for The Torch and has also co-ordinated its murals program, through which artists are commissioned to create vibrant paintings on buildings and walls. Back when he was in jail he wasn’t able to profit from his artworks, so Morris arranged for him to be paid for his NGV commission when he was released. After seeing the good work of The Torch, the Victorian government changed its policy in 2016 to allow Indigenous inmates to sell their art from inside. Indeed The Torch has a large online catalogue of artworks for sale proclaiming “100 per cent of the artwork price goes directly to the artist”. It also holds an annual exhibition called Confined, showing soon at Glen Eira City Council Gallery in Melbourne, where 400 works will be for sale.

Miller says the program has been so successful because it “gives you the resources to learn your correct culture”.

“My father grew up in Moree and it was very segregated, you would just keep a low profile and not do anything like language. It was kept quiet because it would cause you trouble – if you know what I mean?

“The one thing you don’t learn is your culture. The Torch gives you those opportunities and links you up to the right people. They’ve got a research department that would find out information for your art so you’re not doing the wrong thing, you’re not telling someone else’s creation story.”

Miller has seen the program work for a lot of mob.

“Someone goes through their life (receiving) no appreciation or they’re looked down at,” he says. “Then someone starts congratulating them or giving them accolades for their art. It changes a person.”

Blak In-Justice: Incarceration and Resilience is at Heide Museum of Modern Art until July 20. Confined is at Glen Eira City Council Gallery in Caulfield from May 23 to June 22.

Museum of Contemporary Art

Tina Baum

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout