Ritual and energy of a desert painter without peer

The National Gallery of Australia’s Emily Kam Kngwarray exhibition is a worthy and well executed one. But is the Indigenous painter really one of the great artists of the 20th century?

It can be difficult to understand or even to see work that has become too famous, overly-promoted and especially repeatedly reproduced. The Mona Lisa is probably the most notorious case of this phenomenon: a painting that is in fact mysteriously boundless and open, the quintessence of indeterminacy, and yet which to most people might as well be a logo or a brand. Tourists try to take a picture of it to prove that they have been in its vicinity, but none of them could tell you how she is holding her arms.

Many particular paintings and even painting styles have become so reduced to cliches about their meaning or significance that it is hard to encounter them in a fresh way. Tourists line up to see Michelangelo’s Sistine ceiling but have no idea of its subject or meaning; others will like or say they like Jackson Pollock or Mark Rothko on trust, out of conformity or because it is simply easier than making the effort to look and think for themselves.

Monetary value can be an obstacle, too; many years ago when Alan Bond briefly owned van Gogh’s Irises, the record price he had paid hung like a curtain between viewers and the poignantly exuberant little picture of flowers blooming in springtime in the garden of the asylum at Saint-Rémy.

Aboriginal art in Australia today presents particular difficulties, because it comes laden with so many socially and politically motivated prejudices, either for or against, and because it has been allowed to develop in a morass of art market exploitation with little effective critical oversight.

The case of Emily Kngwarreye (c. 1914-96), is somewhat different because in a general way her work is clerly authentic, and was indeed made in the relatively early days of the Aboriginal art boom – what could perhaps be considered the second wave – before the kind of mass production that has developed in the present century.

Even so, she is claimed to have produced an extraordinary number of paintings during a very short career of eight years as an artist, and it seems to be agreed that a lot of these were in fact made by family members; a dealer who handled her work told me years ago that it was not easy to discriminate between the autograph works and those done by others. Another spoke of seeing huge rolls of canvas sent by dealers for her to turn out picture after picture. The current exhibition has raised questions about the sidelining of individuals involved in the earlier exhibitions of 1998 and 2008, and concerns about the influence of dealers who are still making a fortune from the Kngwarreye brand.

But even leaving aside the grimy profiteering of the art business, what do we make of the regular claims that Kngwarreye is, as a gushing fan piece on the ABC website puts it “widely regarded as one of the great artists of the 20th century”? Who holds this view? On what grounds? Or is the author really just telling her readers that this is the most acceptable opinion to adopt and that if you repeat such a claim at a dinner party in a Teal electorate everyone will nod eagerly, adopting a pious and subtly contrite expression?

The opening panel of the NGA exhibition is somewhat more sober: “Her unique style and powerful creative vision gained worldwide attention …” The exhibition itself is well laid-out, whatever the controversies about the selection of the works represented, and allows the visitor to appreciate both the artist’s development and the different styles, or indeed almost genres, in which she worked.

The audience was modest when I visited around midday on a Saturday, mostly made up of older middle-class women, but they were attentive to the works, often stopping to look carefully at particular pictures. Such behaviour should not be surprising in a gallery, but is relatively uncommon in our day of short attention spans; I couldn’t help thinking of the NGV Triennial, whose audience was drifting past one lurid installation after another with all the attention of a teenager scrolling through social media.

Kngwarreye and other women at Utopia in the Northern Territory started working in batik painting in 1977, and it was some 10 years later that they started to paint in acrylic on canvas. Accordingly the exhibition begins with batik, and batik textiles are hung in the successive rooms as well.

Batik, which originated in Java or perhaps even earlier in India, is a technique in which a fabric can be dyed in several colours successively, using wax to protect certain areas of the cloth from contact with the dyestuff. The process is not hard to understand in specific examples, like several two-colour batiks, seemingly of yams or some other plant.

First of all the plant pattern is “drawn” on the fabric with wax; the fabric is then soaked in a yellow dye, which colours all but the waxed areas, which remain white. Then the design is drawn in wax again, but a bit more broadly this time, thus covering and protecting some of the area dyed in yellow. Finally the remaining part of the cloth is dyed in a dark reddish-brown. When the wax is washed off in boiling water, the result is a pattern in white, doubled by yellow, against a brown background.

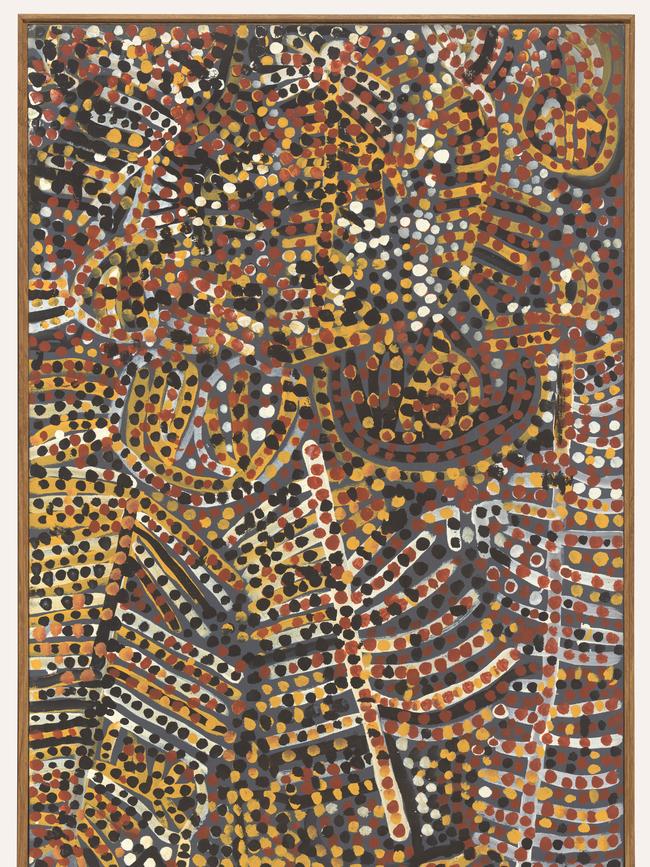

Thus batik painting proceeds, like watercolour, from light to dark, but painting in oil or acrylic – opaque media – proceeds from dark to light, and indeed it is easy to see that many of Kngwarreye’s paintings are built up over dark underpainting. The aesthetic of the batik painting, however, is visible in the soft or blurred edges of her characteristic dots or smudges, which often overlap or merge into agglomerations like nebulae floating against darker backgrounds. One of the best examples of this category is the large painting Kam (1991), from the collection of the NGV.

The pictures characterised by these cloud-like agglomerations of dots are about the artist’s own country and can be thought of as imaginative topographies of real sites, as is literally suggested at the end of the short video that accompanies the exhibition; of course it is a topography that incorporates a sense of spiritual significance and cultural memory as much as objective features such as hills, gullies and watercourses.

Another striking work of this category is Mern Angerr (1992), now in a Swiss collection. It is a large painting, whose composition is dominated by two large, bright nebula-like formations, the one on the right smaller and with its horizontal set against a rain of strongly-marked verticals. It is an impressive canvas which now belongs to the immensely rich collector Bérengère Primat, in her Fondation Opale in Lens, Switzerland. Through her mother, she is an heiress to the fortune of the Schlumberger family, who created the international oil drilling and exploration services corporation SLB, formerly know as Schlumberger, and who moved to Switzerland half a century ago to avoid French inheritance taxes.

I mention this not to question the sincerity of Bérengère’s passion for Aboriginal art, or indeed to blame the Schlumberger family either for their business interests or their desire to manage their tax affairs efficiently, but just to ponder how work of this kind, while undoubtedly poetic and even spiritual, has a kind of bland and soothing quality which is very appealing to the corporate world and those who have made their fortune in it.

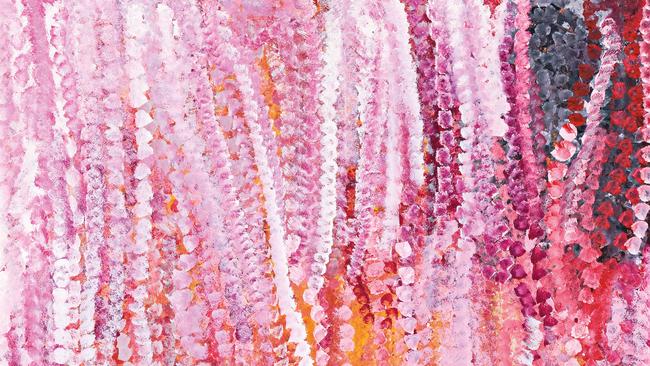

Another set of canvases has long, scribbly linear marks rather than dots, and these painterly forms seem to evoke the tangled growth of the vines of the bush yam, known as Kam, for which the artist was named, or possibly the underground network of tubers. According to a wall label, it is when the surface growth dies off that the tubers are ready to be gathered and eaten, either roasted or raw.

This category of work is perhaps the most quickly executed – spontaneous, if we look on the positive side but perhaps also sometimes careless and variable in quality; in any case this is probably the part of Kngwarreye’s oeuvre that is the most vulnerable to pastiche or imitation. As with any art or craft, however, if we look at these long enough we begin to see which ones have real movement, dynamism and coherence and which look facile or perfunctory.

In the best of them, there is an overall sense of direction that endows the whole picture with a compositional shape, as in an untitled work from 1996 near the end of the exhibition. Here the lower left of the composition, densely painted, is marked by a strong upward drive, while in the upper part of the composition the tangled lines of white, yellow and red become relatively quieter and less dense, allowing the black underpainting to show through.

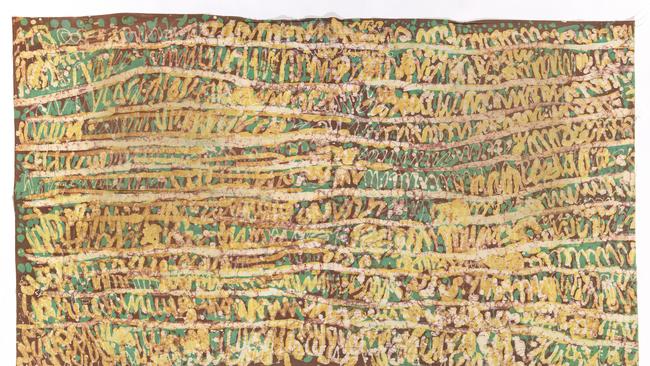

The third category or genre in her work is made up of columns of short roughly horizontal bars, which are said to be derived from ritual painting on women’s bodies, or even ritual scarring in various cultural contexts such as initiation or mourning.

These are the most minimal of her works, but they seem to be painted much more slowly and deliberately, and certainly more systematically, than the scribbly yam paintings.

In the best of them, such as an untitled painting from 1994, predominantly in browns and black on a white underpainting, there is a sober and contained energy. Because of the minimalism of the marks, much depends on the relative speed and energy of each line, and also on its subtle changes of direction, from rising to falling bars. In combination, the constantly varied patterns of movement evoke singing or dancing and one of the exhibition labels suggests that they are ultimately based in the experience of ceremonial dancing witnessed by the artist.

Paintings such as this are, however, very far from the reality of performances such as those enacted in the quite touching video alluded to above – touching yet also almost shockingly alien to the tastes and mores of most of those who like to love Aboriginal art.

Kngwarreye’s paintings are far more serene, aesthetically pleasing and comforting, while allowing their owners to display their wealth, status and moral progressiveness at the same time.

Emily Kngwarreye

National Gallery of Australia to April 28

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout