Paul Gauguin a pedophile? Let’s be clear about the facts

This important survey of the French post-impressionist’s work is mercifully free of irrelevant ideological posturing.

We are fortunate that this Gauguin survey – no doubt the most important art exhibition in Australia this year – was put together by Henri Loyrette, former director of the Louvre, in collaboration with Art Exhibitions Australia.

It is certainly a good thing that the people at the National Gallery of Australia responsible for ludicrously expensive and irrelevant commissions and relentless ideological posturing had so little to do with the present project. I watched the little documentary film at the opening of Gauguin’s World with some apprehension at first, but it turned out to be intelligent, thoughtful and even poetic. If it had been produced by the gallery, we likely would not have escaped self-indulgent hand-wringing over colonialism and pious outrage at Paul Gauguin’s allegedly reprehensible relations with young Tahitian women during his years in the South Seas.

Many Australian journalists, in discussing the exhibition even before it opened, felt compelled to express their disapproval of his behaviour, many even going so far as to use the lazy and sensationalist word pedophile.

Let us be clear about the facts: the age of consent in French law at the end of the 19th century was 13. The artist was therefore not sleeping with legally underage girls, let alone children. For that matter, the French age of consent had been raised from 11 to 13 in 1863; today it is 15. In traditional Polynesian society sexual relations were acceptable from puberty.

Indeed the sexual freedom of the Polynesians fascinated the West from the first encounters in the 18th century to the anthropological studies and popular films of the 20th; for some Europeans their permissiveness was simply promiscuity, while others found in their behaviour evidence of a healthier and more natural expression of sexuality than the guilt-ridden attitudes fostered by Christianity. In his posthumously published Supplement au voyage de Bougainville (1796), Denis Diderot approves of the spontaneous and uninhibited sexuality of the Tahitians, also emphasising that their women retain independence and do not become the property of men.

The question of the agency of the women with whom Gauguin was involved is of course too easily ignored in the ideological haste to condemn him as a colonial exploiter. It has been the focus of a new book on the artist by Nicholas Thomas (recently reviewed by Kate Fullagar), who is also a contributor to the catalogue. In another chapter, Norma Broude also questions the facile narratives about the artist and reminds us of “Gauguin’s progressive and feminist cultural positions”.

This is not to say that Gauguin was without his faults. He effectively abandoned his wife and children in Copenhagen while he sought the more primitive authenticity first of Brittany and then of the South Seas. His behaviour after the crisis with Vincent van Gogh in December 1888 was not very admirable either: after van Gogh had a psychotic breakdown and attacked him with a razor – subsequently cutting off part of his own ear, perhaps as an act of self-mortification – Gauguin simply fled and left his friend to cope with his breakdown alone.

But how relevant is any of this to our assessment of his art? Are we really going to undertake a systematic moral appraisal of a man or woman’s behaviour before judging their work? Where would we stop? How many notable individuals have been neglectful or disloyal spouses or abusive parents? It is particularly dangerous to issue a sentence of cancellation on the basis of changing moral norms: many who now join in the performance of outrage would once have been themselves despised as sexual deviants.

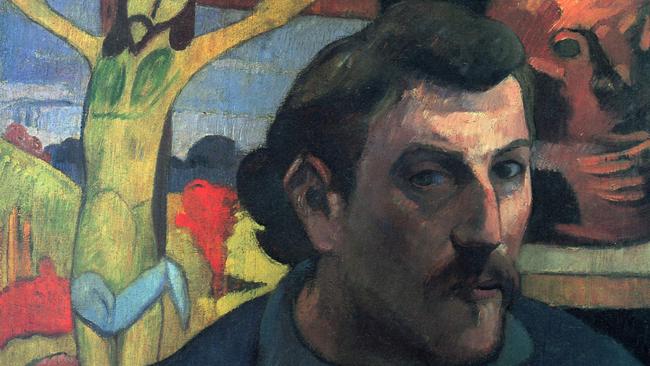

Gauguin (1848-1903) was almost predestined for a life of expatriation; though born in Paris, to a family with a complex and partly Spanish background, he was raised in Peru for several crucial childhood years before returning to France after political upheavals deprived his family in South America of wealth and power. After school and a period in the merchant marine, he became for a few years a prosperous stockbroker, although he was increasingly drawn to art; he was never formally trained but learnt much from the mentorship of Camille Pissarro, a member of the impressionist group who nonetheless considered himself a pupil of Camille Corot and also played an important part in Paul Cezanne’s development. Gauguin showed in several of the impressionist group exhibitions, but his work became increasingly different in its objectives.

By the time of the last impressionist exhibition in 1886, van Gogh, who came to Paris in that year, identified two distinct groups within the movement, what he called the impressionists “du grand boulevard” – those by now represented by the leading art dealers – and those “du petit boulevard” who included painters as different as Gauguin and Georges Seurat. Most of these subsequently would be considered neo-impressionists (Seurat and Paul Signac, joined for a time by Pissarro) or post-impressionist in various distinct ways (Gauguin, van Gogh, Cezanne).

We can see in this exhibition how eagerly the young Gauguin learnt from Pissarro but also from Edgar Degas and even followers of Degas such as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, as well as admiring the older Pierre Puvis de Chavannes. Among younger artists, he was drawn to Emile Bernard’s “cloisonnist” technique; that is, one in which flat areas of colour are bordered by black outlines like the leading in stained-glass windows. With Bernard and others he increasingly adopted a manner that the group called synthetism, in which the optical naturalism of impressionism is abandoned in favour of a quasi-symbolic approach with a greater emphasis on flat pattern.

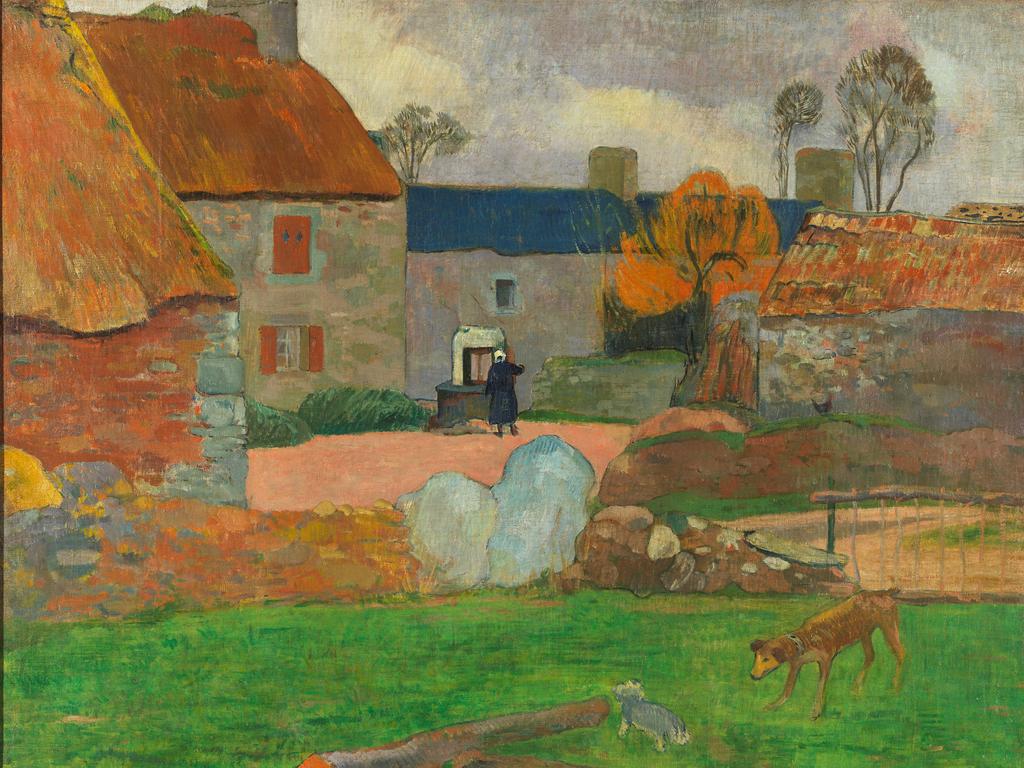

A good example in the present exhibition is Le Toit bleu (1890), a view of a farmyard in Brittany, which the NGA will acquire after the exhibition – a beautiful painting and a worthwhile purchase, although still a youthful work and not representative of his mature style.

Although the perspectival relations between buildings in the foreground and background of this painting are technically accurate, the space is subtly flattened, partly through the omission of aerial or atmospheric perspective, so that we become more conscious than usual of the pattern made on the picture plane by the various areas that represent walls and roofs. At the same time, without being distorted as gratuitously as in later Fauvist painting, local colour is subtly manipulated to produce chromatic tensions between complementaries – the blue roof and the orange of an autumn tree, the green grass in the foreground and the pink gravel of the courtyard, the orange roof tiles and the mauve wall.

Some of this play of flat pattern and artificial colour is inspired by Japanese ukiyo-e prints; in Street in Tahiti (1891), too, perspective is at once dramatised and flattened, as in many Japanese prints, and in a way that Japanese artists themselves ultimate adapted from Western perspectival images. In Mahana Ma’a (1892), on the other hand, a view of the Tahitian forest is reduced to an almost abstract chromatic composition of complementary patches of colour, rather as Sir Joshua Reynolds once described the chromatic balance of Peter Paul Rubens’ paintings as being like a bunch of flowers.

Gauguin never seems to have been happy in France, often referring to himself as a savage and longing to live in a place where life was simpler and closer to nature. Early voyages took him to the Caribbean but he eventually settled in Tahiti, in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, and later died in the Marquesas Islands, still part of French Polynesia but a considerable distance to the northwest. Here he found not only islands of great natural beauty but also an attractive and appealing people and, despite the inroads of missionary activity and the spread of Christianity, vestiges of a traditional culture. He learnt the Tahitian language and was fascinated by old Polynesian religious beliefs, surviving ancient cult practices, and the structures of a once hierarchical and feudal society.

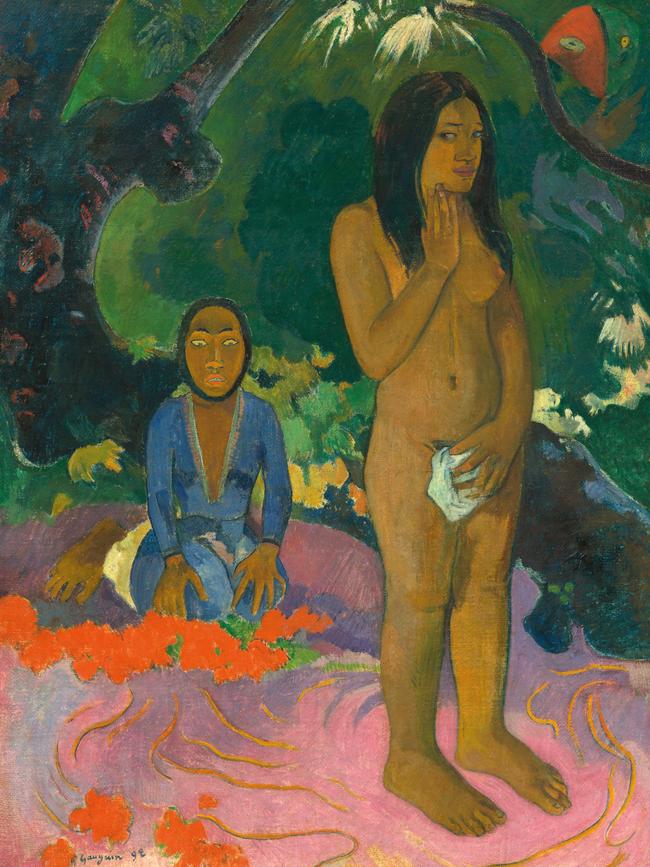

His images of Polynesian women have a kind of dreamlike beauty but are in fact never overtly sexualised. On the contrary, they are compact, relatively stocky figures who stand confidently even when naked, as in Two Nudes on a Tahitian Beach (1891-94); their firm and poised bearing may remind us of Johann Winckelmann’s observation that the vigorous and healthy bodies of the ancient Greeks, so different from the sickly and flabby physiques of contemporary Europeans, could still be found among the American Indians.

In other paintings, too, the Polynesian figure is never mincing, coquettish or prudish as a contemporary French girl could be: in Tahitian Women (1891), the artist is interested in the solidity and volume of the two figures, and the way that one on the left supports her weight on her right arm. These are strong and matter-of-fact women, in no sense the passive objects of some imagined colonial gaze. In Three Tahitians (1899), the half-length figures again have a classical strength and self-possession; they have been compared to traditional iconography of the three Muses, except that the one in the middle is male.

Yet Gauguin is not simply rediscovering the neoclassical ideal in an unspoilt race, as Winckelmann suggests, let alone indulging in a fantasy of innocent and happy natives. He knows that just as the Polynesian social world could be violent and oppressive, its spiritual universe, like that of all animistic peoples, was filled with demons, spirits and ghosts. These are the terrors evoked in one of his most mysterious and elusive masterpieces, Spirit of the Dead Watching (1892), unfortunately not in this exhibition.

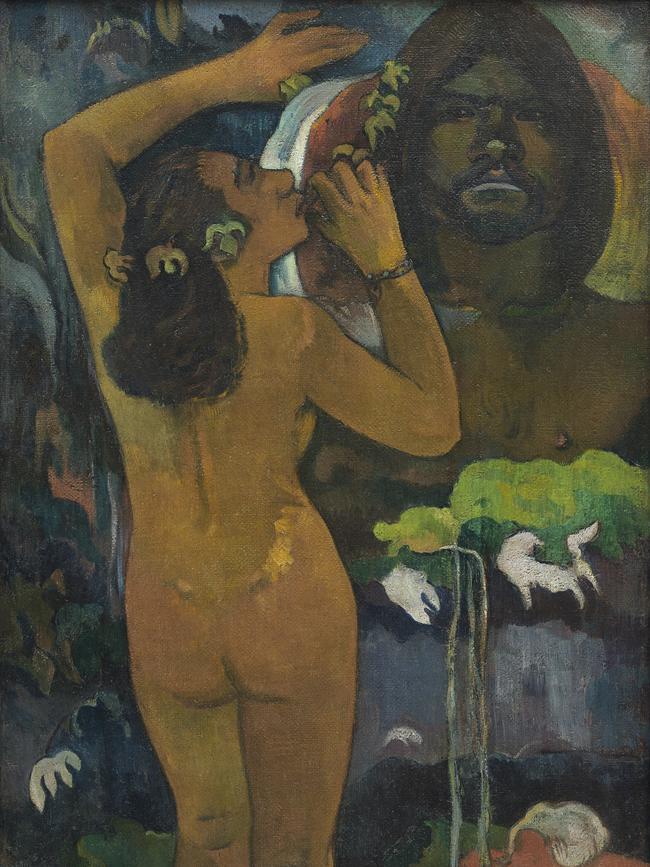

In many of Gauguin’s compositions the Tahitian figures are seen in actions or postures that recall classical or Christian iconography: thus a girl covers her breasts in a way that would probably never occur to a Polynesian but echoes the Venus Pudica type in ancient sculpture. The same attitude can be adapted to represent Eve’s shame after the Fall; or she may be evoked in the figure of a girl reaching into a tree to pluck a piece of fruit. By the time Gauguin painted these women, they had all been converted and had been introduced to Christian ideas of guilt and shame, so it was not necessarily incongruous to make a Polynesian girl re-enact the primal sin of Eve. But Gauguin’s purpose was neither to use his Tahitian models to illustrate a Christian allegory nor to represent some anthropologically accurate version of their pre-Christian beliefs and fears. It seems rather that he found in them a way to renew elements of biblical belief and reinvigorate them in this synthesis with the dark and resonantly primitive animistic beliefs of the South Seas, to find some way to articulate imaginatively the incomprehensible relation between beauty and jouissance, on the one hand, and the tragic realities of sin, illness and death.

Gauguin’s World

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, to October 7

Gauguin’s World

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, to October 7