Paul Gauguin: View from a roving brush

The complicated legacy of Paul Gauguin — sailor, stockbroker, painter — continues to be debated. Is it anything more than seedy colonial opportunism?

No one could say Paul Gauguin had an uneventful life.

A sailor with a lust for the sea and exotic ports, he spent his childhood in Peru and when still a teenager he sailed the world with the merchant navy. A Sunday painter and weekday stockbroker in Paris, he traded in his office career – and his family responsibilities – to devote himself wholly to his art.

A friend of artists including Camille Pissarro, Edgar Degas, Emile Bernard, and – most disastrously – Vincent van Gogh, he abandoned his early Impressionism and strode out boldly on his own artistic path.

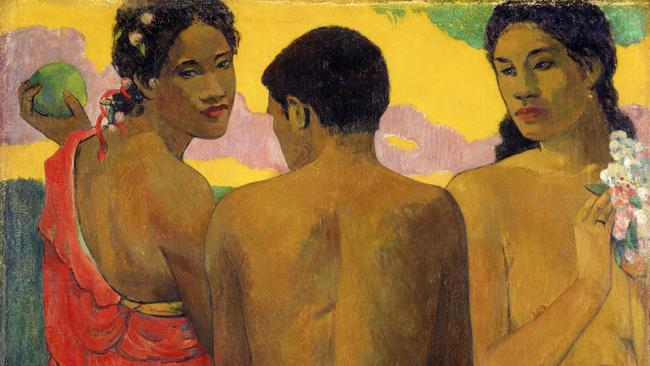

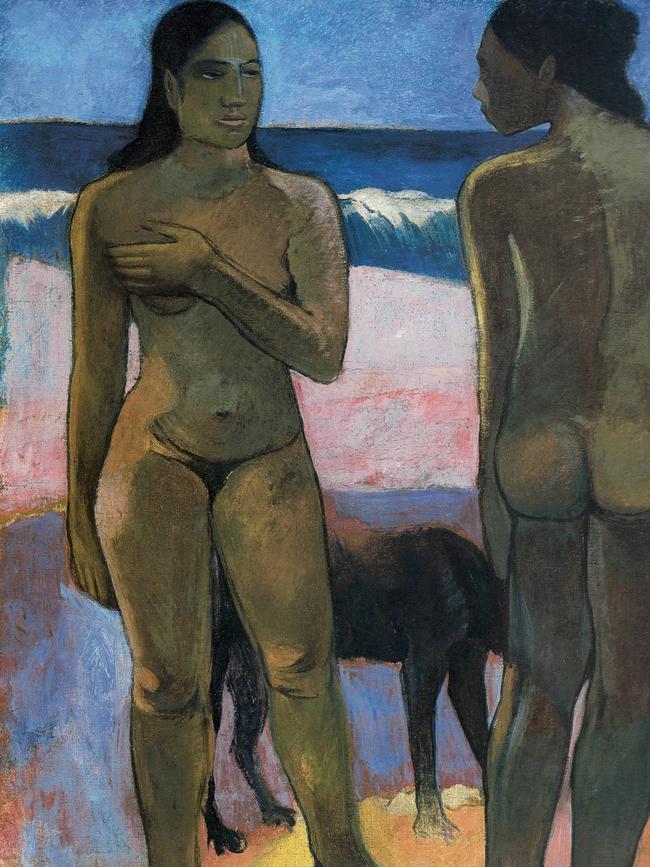

He is best known, of course, for the two periods he spent in the South Pacific, first in Tahiti, and then in the final years of his life in the Marquesas Islands. It was there he made his famous paintings of lush tropical landscapes, strange idols and voluptuous women. They gave rise to the myth of Gauguin as the romantic artist-adventurer, and to his reputation as something of a sex tourist and cultural thief.

This is the fascinating, complicated figure with which any modern exhibition of Gauguin must contend. Gallery-goers will soon have the opportunity to encounter him in the first dedicated exhibition of his work in Australia.

Opening at the National Gallery of Australia in June, Gauguin’s World: Tona Iho, Tona Ao tracks the artist’s travels across the globe, from one of his earliest paintings in big-sky Impressionist mode, to pictures made in Copenhagen, Brittany and the Caribbean, and his intoxicatingly rich period in Polynesia.

“It’s always a kind of trip you do with Gauguin,” says Henri Loyrette, the distinguished former director of the Louvre and the Musee d’Orsay who has curated the exhibition.

“What is interesting for me is to see Gauguin from Oceania – you don’t look at him in the same way when you start at the end, looking back … At the end of his life, when he moved to the Marquesas, he stayed for a year and a half and he knew he was dying, he knew it was his last journey.”

The large exhibition will be surprising for those who know Gauguin only from his well-circulated Polynesian images. As well as his paintings, it includes prints, ceramics, carvings and other works – about 140 in all, from lenders across the world – alongside examples of traditional and contemporary art from Polynesia.

As such, the exhibition represents an important reacquaintance between the artist and the Pacific islands. The Tahitian phrase in the title – tona iho, tona ao, “his own, his world” – evokes Gauguin as a singular artist and the world as he perceived it. But very little of Gauguin’s artistic output, and none of his major paintings, remains in Polynesia.

It means that Polynesian people, including Miriama Bono – an architect and former director of the Museum of Tahiti and the Islands, which has contributed to the Canberra exhibition – have had very little direct knowledge of the artist who remains strongly identified with their islands.

“He is a stranger for us,” she says.

It’s for this reason I’ve come to Paris and not to Papeete to see many of Gauguin’s paintings and other works before they are shipped to Australia. The Musee d’Orsay – the French national museum of 19th-century and early modern art – is the largest single lender to the Canberra exhibition, and significant works on paper are coming from the Bibliotheque Nationale de France and other collections.

On a damp winter day in February, I decide to walk to the Musee d’Orsay and the route I take – through the bare trees in the Tuileries Garden and across the Seine – is as Parisian as you could want. An accordion-player is playing La vie en rose, and buttery, garlicky smells waft from bistros packed with Sunday lunchers.

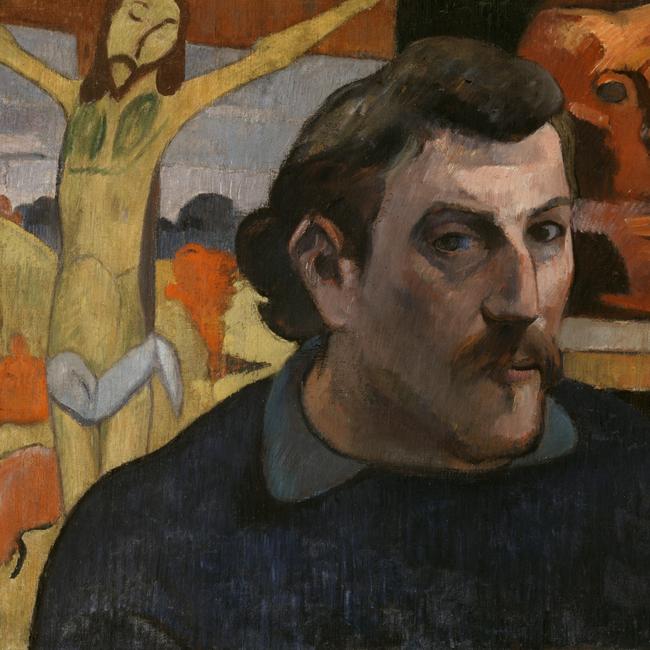

The Gauguin collection at the Musee d’Orsay recently has been rehung, and it is almost impossible when entering this comprehensive display not to feel the force of a powerful artistic personality. To get my bearings, I stand for a moment in front of one of Gauguin’s well-known pictures, which is coming to Canberra, Portrait of the Artist with the Yellow Christ.

This compelling picture highlights several of Gauguin’s preoccupations, not least with himself. On the left is a painting-within-a-painting, showing (in reverse) his picture of the Yellow Christ – a polychrome wooden crucifix from a chapel in Pont-Aven, the town popular with artists in Brittany. On the right of the picture is a ceramic sculpture of a head – it could be a self-portrait of Gauguin – that may recall pre-Columbian sculpture he’d seen during his childhood in Peru or on later travels.

Between these two potent images is the portrait of Gauguin himself. His dour expression may have something to do with unfulfilled romantic longing – he was in love with his friend Emile Bernard’s sister – but he was also in the habit of depicting himself as a kind of martyr, ready to sacrifice everything for his art. The painting therefore can be seen as a personal credo, as Gauguin – through the sheer force of artistic personality and will – holds seemingly disparate elements together in the one composition.

The picture is dated 1890-91, when he was about to embark on his first voyage to French Polynesia: he set sail from Marseilles on April 1, 1891, and landed in Papeete on June 9. This is when things start to get really interesting.

Dominating the Gauguin rooms at the Musee d’Orsay is the large timber fixture that was at the entry of his last home in Polynesia, in the Marquesas Islands. Carved by Gauguin, it has voluptuous female figures adorning the vertical supports and, across the lintel, the name he gave to his island home, Maison du Jouir – not unreasonably translated as House of Pleasure, but more accurately as House of Orgasm.

Step through the door, if you will, and into Gauguin’s garden of earthly delights.

The first thing you notice is the explosion of colour. Violet. Mango. Rainforest green. Bougainvillea pink. It would be wrong to say that Gauguin only discovered colour in the South Pacific. Years before, he had abandoned the feathery brushstrokes that are the Impressionist’s response to evanescent light in favour of strong outlines and bold blocks of colour – a style known as cloisonnism. But something else was turned on in his colour palette when he arrived in Tahiti, as if the switch had been flicked to tropical. Everything becomes richer, juicier, heady and fragrant. The colours he uses in, for example, Street in Tahiti, 1891 – painted during his first year on the island – could not describe a street in Paris or Brittany.

The atmosphere of languid sensuality can almost be felt on the skin, and Gauguin couldn’t wait to show what he’d been up to in the South Pacific. Constantly short of cash, he shipped paintings back to Paris and arranged to have an exhibition there in November 1892. He arrived back in France with the painting that he hoped would be noticed and command a high price. Mana’o tupapa’u, or Spirit of the Dead Watching, shows a naked young woman lying stomach-down on a bed, her frightened face turned towards the viewer. The deep violet background suggests it is night, and behind the girl, seen in stony profile, is a spooky-looking figure in a hood – a tupapa’u, or ghost.

The picture caused a sensation all right – it is probably Gauguin’s most notorious. (In Canberra, it will be represented by a woodcut print, made a year or two after the painting.) We know from Gauguin’s unreliable memoir about his Tahitian sojourn, Noa Noa (Fragrance), that the girl in the painting is his child-bride, Teha’amana (named as Tehura in the book). He describes his first meeting with her – “a child of about 13” – and the night he returned home to find her “immobile, naked, lying face downward flat on the bed with the eyes inordinately large with fear”. Spirit of the Dead Watching, the painting, appears to be an illustration of this scene.

“What it is above all about for him is the woman’s fear of the ghost,” says Nicholas Thomas, an Australian-born anthropologist and author of a new book, Gauguin and Polynesia. “He acknowledges that some people will look at (the picture) and say it’s about sex. He’s saying, ‘Well it’s not about sex, it’s about the power of the other world for Polynesians, the power of superstition’.

“Ghosts loom very large in everyday islander belief … He didn’t have a very deep understanding of the more complex or intricate aspects of Polynesian belief, but he did understand that spirits were perceived to be powerful and present, and could see them as threatening.”

I’ve joined Thomas at the Musee d’Orsay for a tour of the Gauguin works and he brings a fascinating perspective to them. Today, he is the director of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Cambridge, but when he was a young doctoral student in the early 1980s, he made his first visit to the Marquesas Islands to study local history and culture. He has been able to observe the customs and beliefs of Polynesian people and compare them with the fact-fictions of Gauguin’s art and writings.

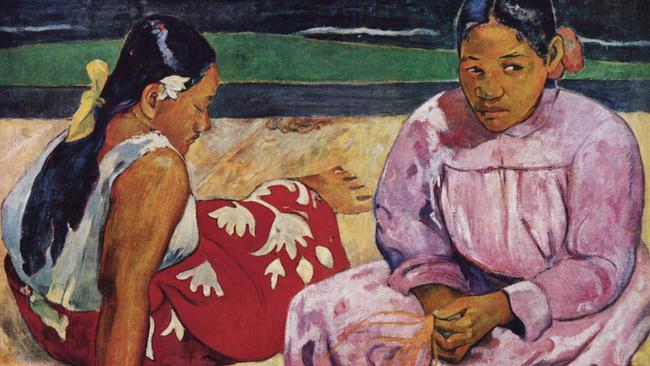

We look at the painting called Femmes de Tahiti (Women of Tahiti), which Thomas says is almost certainly a portrait, possibly a double portrait, of Teha’amana. It shows two women sitting on the floor of a veranda or some kind of platform. The figure on the left, her face cast downwards, is wearing a printed cloth wrap or sarong called a pareu, while the figure on the right, sitting towards the viewer, wears a demure pink dress in the style introduced by Christian missionaries in the early 19th century.

Thomas says Femmes de Tahiti is a more or less accurate depiction of a social scene that Gauguin would have encountered daily in Polynesia – people sitting on the ground in the heat of the day, perhaps talking or retreating into their private thoughts.

“I was struck by a kind of disconnect between the image of Gauguin as an artist, and the critical image of Gauguin that has become increasingly prominent in recent years – where this is an artist who sexually exploited girls or young women, and who paints in a very voyeuristic way,” Thomas says.

“I can understand why there is that reaction, because some of the work is sexualised and he paints some nudes. What is also surprising is that the bulk of his paintings of Polynesian women are women who are dressed, and they are dressed in the clothes … of the 1890s when many of them had been Christians for several generations. He is often responding to the people who were around him, the way they dressed, and we know how they dressed from photographs and other images of Polynesians at the time.”

What of the charge that Gauguin was no better than a sexual predator who took advantage of underage girls in a remote French colony? After Teha’amana, he had two other Polynesian lovers, Pau’ura and Vaeoho Mary Rose.

Thomas does not excuse Gauguin when he says that the artist’s relationships with girls or young women in Polynesia are “easily misrecognised”. He points out that the age of consent in France at the time was 13, and that Tahitian girls could be married at 14. The dynamics of gender relationships also were different from those in France, as women had relatively high status and autonomy in Polynesian society.

“What’s striking about the stories of the women Gauguin was involved with was that they really came and went,” Thomas says. “They had their reasons for entering into those relationships and they had reasons for ending them when they wanted to end them …

“The bigger problem is not that he is having relationships with younger women, but that certainly later in his life he is carrying syphilis, and he is passing that on to other people. In that sense his behaviour was like that of many other colonial men of the period – maybe no worse, but certainly no better.”

The image that Gauguin helped create of the sexually available Polynesian woman has proved to be particularly stubborn and continues to irk more than a century after his death. With no access to Gauguin’s Polynesian paintings other than through reproductions, Tahitians are unable to interrogate them as it were in real life, but continue to be associated with their unwelcome cultural freight.

“The image of Polynesian women, that they are there to just please men – of course that is something that we are unhappy with,” says Miriama Bono, who has Tahitian and Italian heritage. “I, like many Polynesian women, am trying to fight against that and to show that we are much more than that … (Visitors to Tahiti) are always asking us to have an opinion about Gauguin and I am always saying, ‘We have something else to say than just talking about Gauguin’. The fact that he is still the question shows that we still have that problem today.”

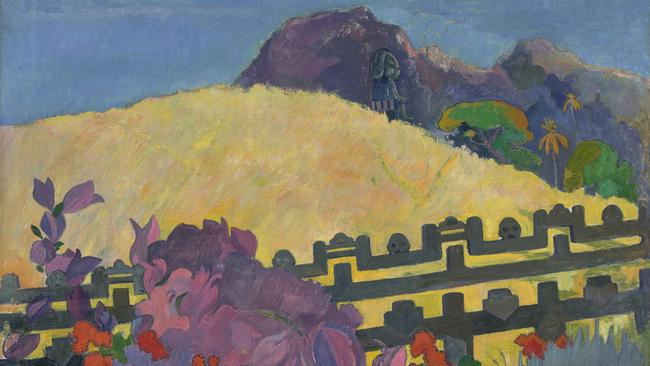

Just as there are nuances to Gauguin’s posthumous reputation of sexual adventurism, the accusations levelled at him of cultural appropriation also are not so black and white. Certainly, Gauguin borrowed and adapted for his own artistic purposes the sacred image of the tiki – representing the ancestor spirit – and he made carvings that used designs like those of Polynesian tatau (tattoo). The Canberra exhibition will have a fascinating pairing of Gauguin’s painting, Parahi te marae (The Sacred Mountain) and an example of Marquesan traditional art, an ear ornament carved from bone. Brought together, they show how Gauguin mimicked the design of the Marquesan ornament in his painting.

And yet, Bono says the atmosphere of tropical mysticism that Gauguin summoned also is evidence of his desire to understand Tahitian and Marquesan beliefs.

“I never heard Marquesan people or Tahitian people complaining about Gauguin or other artists using symbols of Polynesian culture in their painting,” she says. “We are of the opinion that you have to understand and you have to be curious about the culture that you are representing.”

As Loyrette, the exhibition’s curator, explains, Gauguin was interested in much more than merely quoting Polynesian motifs.

“What was important for him was nature, the landscape, the colours, the smell, the music,” he says. “It was much more global than just a formal interpretation. If he wanted that, he could have stayed in Paris.”

I’ve come with Loyrette to the Biblioteque Nationale de France, whose historic Richelieu branch in Paris has an impressive collection of Gauguin’s works on paper. Nave nave fenua (Delightful Land), from the Noa Noa suite, shows a single female figure – like those carved on the panels from the Maison du Jouir – in a lush landscape. A second, Te faruru (Here we make love) depicts two figures entwined and, behind them, the spectre of a tupapa’u spirit.

There’s also a beautiful example of one of Gauguin’s woodblocks, the incised blocks from which he made prints. Le calvaire Breton (Breton Calvary), from 1898-99, harks back to the Yellow Christ and other religious sculptures Gauguin encountered during his stays in Brittany a decade earlier.

The dark block of smooth timber, small enough to fit in a shoebox, bears the traces of Gauguin’s hand-carving in its textured gouges and rough-hewn figures. The image and technique could almost be medieval – and what’s surprising is that Gauguin carved it not in Brittany, but in Tahiti, from native Tahitian timber.

As such, it speaks to the thesis that Loyrette is making with this exhibition: that Gauguin, despite all his peregrinations and his years in the Pacific, remained at heart a French artist and firmly rooted in the Western tradition.

On Hiva Oa, in the Marquesas Islands, Gauguin built his Maison du Jouir amid the coconut palms, minutes from the beach. As he described it, the house had “everything a modest artist could dream of”: bed, kitchen, studio. In this tropical paradise he surrounded himself with reproductions of artists he admired – works by Manet, Rembrandt, Michelangelo, Holbein and others – and his makeshift gallery shows how closely he considered himself part of Western art, not removed from it.

“It’s a reflection on what he did, what he wanted to be his legacy,” Loyrette says.

“He was, in a way, in the tradition of the big names – from Giotto, to Rembrandt, Ingres and so on … And that’s very interesting, his point of view at the end of his life. He remained a Parisian artist to the end.”

One of Gauguin’s final paintings makes a fitting conclusion to the Canberra exhibition. Portrait of the Artist by Himself was painted in 1903 in the weeks or months before he died at age 54 – possibly from syphilis, heart attack, or an overdose of laudanum. There are no allusions to Christ, no quoting from other artists, no exotic motifs or other distractions. You’d have no idea he painted the self-portrait on a tiny island in the middle of the Pacific.

But even this final testament is not as simple as it seems. Loyrette notes that the portrait’s small, narrow format, the lack of adornment, and the focus on the face, slightly turned, recall the Egyptian funerary portraits that Gauguin would have seen in the Louvre, half a world away in Paris.

At the last, Gauguin was searching for the exotic, some faraway land or time. It’s as if this inveterate wanderer couldn’t help himself. As Loyrette says: “He looked at everything.”

Gauguin’s World: Tona Iho, Tona Ao is at the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, June 29-October 7. The writer travelled to Paris with assistance from Art Exhibitions Australia.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout