Paul Gauguin was a predator but his creations deserve to be seen

Paul Gauguin preyed on young girls and Rolf Harris is a convicted pedophile. The latter’s works will fade from view, but should a master’s work be banned?

“Is it time Gauguin got cancelled?” asked a recent New York Times headline. It echoes the question that you will hear if you pick up the audio guide and walk through the latest Gauguin show at the National Gallery in London. This is an exhibition of portraits painted by the stockbroker-turned-artist who, abandoning his wife and family, headed off to the South Pacific to paint.

In French Polynesia, exploiting his privileged colonial position, he indulged in his taste for beautiful adolescents. He “repeatedly entered into sexual relations with young girls, ‘marrying’ two of them and fathering children”, a wall text informs the viewer.

Galleries are increasingly moving away from the safe — and, let’s face it, slightly dull — territories of traditional art history, to examine pieces from a more lively and more relevant modern stance. Public sensitivities to sexuality, colonialism and race have changed enormously since the days when most of the pieces in our museums were made. Art institutions are reassessing their legacies as a result.

Exhibitions that previously might have focused on formal developments encourage us to look from a more nuanced perspective. It’s no longer enough merely to acknowledge that, in the old days, attitudes were different. Corrective explanations are made. In a recent Tate retrospective of Natalia Goncharova, the term “primitivism” was qualified. It was coined, visitors were informed, to describe “acts of appropriation from other cultures”. It is a word, the wall text said, now “recognised as being offensive, implying that those cultures were inferior to or less advanced than western Europe”.

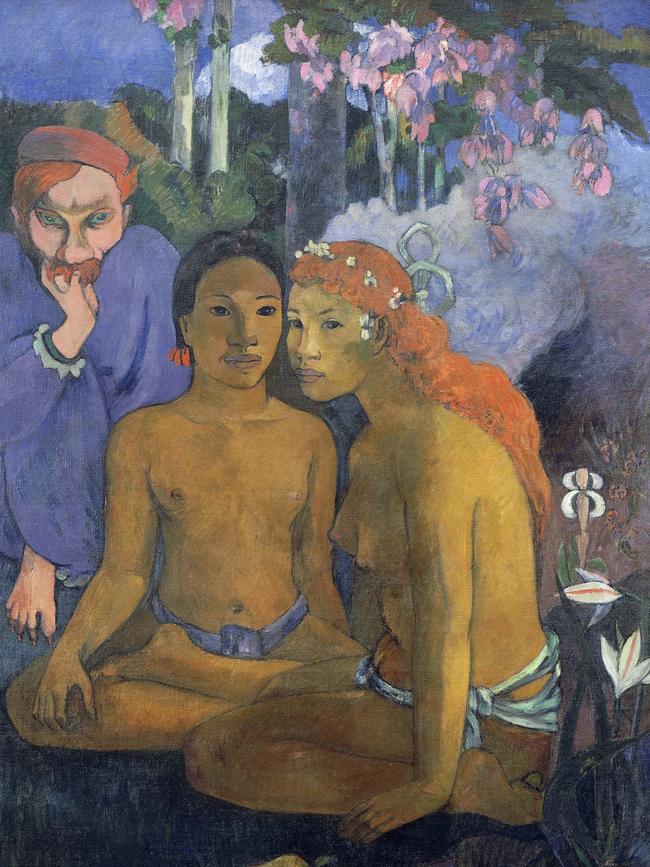

If Gauguin were around today he would certainly be vilified. A picture of a pair of dusky maidens, sitting cross-legged in the pink-flowered forest, may be as visually appealing as it is art-historically significant. But its title — Barbarian Tales — has an unacceptable ring to the modern ear. And that’s the least of it. Gauguin would stand trial for pedophilia today. That melancholy girl in the high-necked maternity dress of dark pink is quite simply the victim of child abuse. The behaviour of Gauguin, a syphilitic predator in a South Seas paradise, is as deplorable as that of today’s sex tourists to Thailand, the Philippines or Cambodia. Yet his bright canvases remain a box-office hit.

Should we stop looking? Most definitely not: not, at least, if we don’t want to have blindfolds issued as we step into our public art collections. Because where would such moral censorship stop?

As Christmas approaches, would we have to avert our eyes from all those images of Baby Jesus, wriggling naked in his manger? Leo Steinberg, the post-war American art historian and critic, famed for his persuasively elegant investigations into Renaissance paintings, would turn in his grave. His famous study of the sexuality of Christ put its focus on what he called the “ostentatio genitalium”: the display of genitalia that so often figured in devotional paintings, but which for more than 500 years had been “tactfully overlooked”.

The prominence given to a baby’s penis might make us feel more than a little uncomfortable, but to ignore it, Steinberg argued, would be to miss an important message. The emphasis, he explained, was a manifestation of an incarnational theology made explicit in the sermons and pious literature of the time. The blood shed at the circumcision was seen as the first offering of the redemptive sacrifice.

Steinberg’s book stirred debate when it appeared in the early 1980s. But it was reprinted later along with a full account of the controversy and with Steinberg’s interpretation confirmed in an appendix by a Jesuit theologian. Now it is recognised as having added to our understanding of Renaissance imagery.

Our museums and galleries are packed with pictures that, at best, risk causing the prudish embarrassment, at worst stir grave suspicions about their creators. But more generally these works offer reflections of the social attitudes of their eras.

The Ancient Greeks, for instance, viewed the toned, muscular body of a nude as honourable and virtuous. To the Victorians, such nakedness was a mark of immorality and vice. Sculptures were adapted with an appositely placed fig leaf.

Attitudes shift. Egon Schiele depicted his subjects — frequently himself — in states of explicit and often self-stimulated arousal. Masturbation, however, was taboo at the turn of the 20th century — and going blind was the least of it. Until Sigmund Freud’s studies into sexuality spread more tolerant attitudes, doctors would subject patients who suffered from autoerotic compulsions to often brutal physical mutilations. Schiele was tried on a charge of incitement to debauchery and imprisoned.

A more liberated modern society has cleared his name. Schiele’s images, it might be argued, speak less of voyeuristic titillation than of uncompromising intimacy. Here is an artist who confronts our human condition with unflinching honesty. Schiele is now feted as a purveyor of truth. Meanwhile, the fig leaf is treated as an object of derision and jokes.

Yet what of art that speaks of more sinister problems: of rape, pedophilia, incest, violence, racism, homophobia or sexual abuse? Can you admire such images without becoming in some way complicit? Can you value the work of someone whose private acts you find appalling? Do the proclivities of those responsible for artistic or intellectual works have to be taken into account in their appreciation?

These are complicated questions, but ones that arise increasingly frequently.

Graham Ovenden, a founding member, in 1975, of the Brotherhood of Ruralists, was found guilty of six charges of indecency with a child and jailed in 2013.

The Tate removed images of his work from its galleries and website. It was no great loss to the art world. His sexually tainted pictures of child models were aesthetically indifferent.

The same might be said of the convicted pedophile Rolf Harris. He did not betray his proclivities in his anodyne artworks, yet you can be sure that even his portrait of the Queen has disappeared from public view.

No one will miss it. But it’s decidedly more difficult when it comes to masters at the heart of our canon. Pervert or painter? Manifest racist or distinguished old master? It’s a contested terrain.

Think of all those images of an Aryan Jesus. What white supremacist message do they convey? Diego Velazquez painted the dwarfs who once served in royal courts: human toys for the nobles. Caravaggio’s Amor Vincit Omnia presents a titillating Cupid, barely more than a toddler, tantalising his viewers with sparkling eyes and splayed legs.

Are we revelling in the violence of rape when we stare at Titian’s Tarquin and Lucretia? The fully clothed aggressor lunges forward with raised dagger and a look of insatiable desire. His horror-struck victim, ripped abruptly from sleep, recoils in pure terror. You can see the fear in her eyes. Dare we look at the disturbing images of Otto Dix? Should Balthus’s pre-pubescent Lolitas, lounging insouciantly, knickers on show, be banned?

The dilemma extends throughout culture. Shakespeare was manifestly antisemitic. Anthony Trollope’s novels might not seem such a jape when you discover their clearly stated disgust of Jews. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is no longer an innocent story once you know about Charles Dodgson’s photographs of children. Benjamin Britten’s music for children has long been clouded by John Bridcut’s biography addressing his obsession with young boys. Should we refuse to listen to the songs of Michael Jackson, or to watch the films of Woody Allen until the suspicions that surround him are cleared up?

Each era examines art from its own perspective. We study our legacy from our 21st-century stance. Our attitudes are quite naturally slanted by what we know of the lives and the attitudes of their creators. Velazquez, for instance, appears to bring a profound sense of compassion, an awareness of the complexity of truth, to his depictions. Take his A Dwarf Sitting on the Floor. This small bearded man examines us critically. His stare is unsubjugated. He seems anything but awed by our presence. He may have been left to sit on the ground, like some insignificant object. But it is his human dignity that prevails.

Compare this with Rodin, who we feel is increasingly compromised by his biography; by stories of his bullying disrespect for female models. Will you look at a Lowry in quite the same way once you have discovered the erotic brutality of his private fantasies? Eric Gill’s sculptures are compromised by our knowledge that he habitually raped his daughters.

Yet to boycott the work of an artist feels dangerously akin to the medieval smashing of statues; to Savonarola’s bonfires of the vanities, to the Nazi destruction of “degenerate” modernism or Islamic State’s demolition of antiquities. Merely erasing our past does not help. Rather, it feels craven. Art is a great revealer. It can lay bare the whole person — both maker and looker. It holds up the ethos to which it belongs and allows for discussion that adds layers and understanding and depth.

Art can provide a safe forum for the contemplation of potentially explosive political issues. It lets us venture securely into what might otherwise prove a dangerous space.

Leave it to our contemporary artists to address, with the benefit of hindsight, our historical record. They can comment on colonialism, address antisemitism, argue human rights. Leave it to curators to alter the way in which we tell their stories. They can disrupt our mythos of a single triumphant Western civilisation; tell the true story of Europe’s history of empire and trade; challenge the notion that culture is Christian or uniformly white; highlight the often shameful history of their collections.

Much can be done by shifting the emphasis of exhibitions, changing the language of labels, offering catalogue arguments that suggest new contexts. But simply to turn away is to reject the radical message of history.

Gauguin’s perversions, not his painterly creations, are abhorrent. His canvases need not be demonised, quite the opposite. It remains our duty as members of a civilised society to openly confront artworks that speak of our history and human nature — and include its worst flaws. By showing us past mistakes and highlighting appalling failings, art can serve a far more important purpose than the mere offering of aesthetic pleasure. It can offer lessons for the future to build on. Is it time Gauguin got cancelled? That question was certainly rhetorical. Rise to the challenge. That does not mean giving some gut answer and then burying the problem under a ban. It means opening up debate. Museums hold the clues to a better future in their historical halls.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout