National Gallery of Australia acquires $9.8m Paul Gauguin painting

A major new acquisition will help deepen conversations over Paul Gauguin’s troublesome legacy, says National Gallery of Australia director Nick Mitzevich.

A $US6.5m ($9.8m) artwork by artist Paul Gauguin has been acquired by the National Gallery of Australia, making it the first painting by the French post-impressionist and symbolist to enter an Australian public collection.

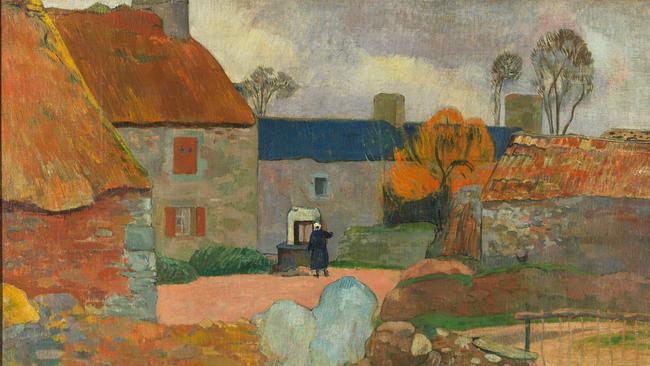

His Le toit bleu or Ferme au Pouldu (The Blue Roof or Farm at Le Pouldu) (1890) was purchased from an international private collector and acquired by the NGA Foundation through a blend of public and private funds, the NGA has confirmed.

The 70cm x 90cm landscape, on show at the NGA’s major exhibition Gauguin’s World: Tona Iho, Tona Ao, was painted by the artist in Brittany, shortly before he travelled into the Pacific, where he would make some of his most famous paintings and develop a historic reputation as a sex tourist and cultural thief.

NGA director Nick Mitzevich told The Australian a Gauguin painting was a missing piece of the art history puzzle for the Canberra institution. “I was always conscious there was no major Gauguin painting in Australia,” Dr Mitzevich said of the work, which last sold at auction in May 2000 for $US5.2m. “Paul Gaugin is a divisive and important figure, and I’ve been on the hunt for (one of his paintings) for a long time. We found one that’s perfect.”

The Blue Roof or Farm at Le Pouldu features at its centre a woman drawing water from a well at a rural homestead. The titular blue roof – a bar of deep cerulean that dissects the work’s top third – is a salient portent of the colour to come just a year later when the artist would leave Paris for a new life, and a new style, in the Pacific islands.

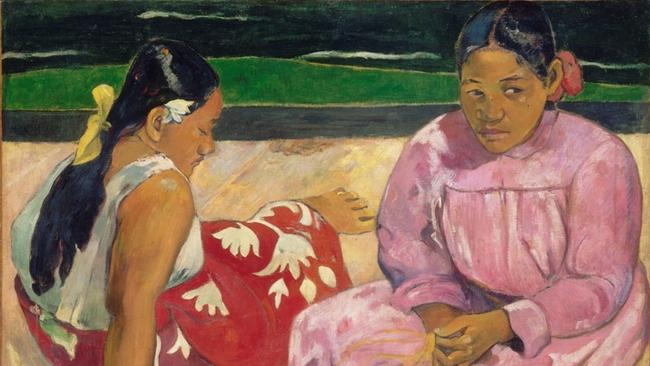

Oceania was where Gauguin’s painterly legacy ultimately would be cemented – his colour-filled representations of young islander women have fetched prices in the hundreds of millions – but it’s also the point from which his personal reputation has come under scrutiny. Gauguin had many sexual relationships with, and was married to, Pasifika teenagers in the late 1890s before his death in 1903. His work also has been criticised as having typecast Polynesian women as passive, primitive objects of lust and mysticism.

Dr Mitzevich said the gallery had embraced “difficult conversations” over the artist’s legacy, and said the acquisition of this pre-Pacific work would deepen those discussions. “For us to be relevant in the 21st century, we need to bounce from past to the present,” he said, pointing to multiple NGA education programs and the Gauguin Dilemma, a four-part podcast series hosted by Sosefina Fuamoli, that discusses the artist’s legacy. “We can’t, and don’t want to, ignore any part of that history. We need to distil it.”

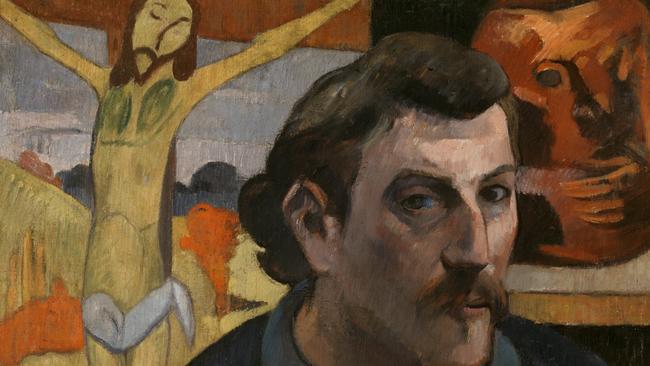

Gauguin is a something of a touchstone for cancel culture in the visual arts. For decades, the art world has wrestled with his legacy: master or monster? Or both?

The NGA is not alone in being on the front foot with audiences. In 2019, at London’s National Gallery, the show’s audio guide began with the line: “Is it time to stop looking at Gauguin altogether?”

In 2018, at New York’s Metropolitan Museum, guerrilla artist Michelle Hartney went the full Banksy and replaced Gauguin artwork descriptions with her own.

Under the French painter’s famous Two Tahitian Women (1899), she placed a plaque that read: “We can no longer worship at the altar of creative genius while ignoring the price all too often paid for that genius … There is no artistic work, no legacy so great, that we should look away.”

Australian-born anthropologist Nicholas Thomas, author of the new book Gauguin and Polynesia, told The Australian earlier this year the issue was complicated by shifting social norms. While not excusing Gauguin’s behaviour, Professor Thomas said at the time, the age of consent in France was 13; Tahitian girls could be married at 14. Further, he said, women in Polynesian society had relatively high status.

“What’s striking about the stories of the women Gauguin was involved with was that they really came and went,” Professor Thomas said.

“They had their reasons for entering into those relationships and they had reasons for ending them when they wanted to end them. … The (other) problem is that later in his life he is carrying syphilis, and he was passing that on to other people. In that sense his behaviour was like that of many other colonial men of the period – maybe no worse, but certainly no better.”

His Breton period was a turning point for Gauguin, who had begun in the late 1880s to isolate himself from society and his family. Of his frequent sojourns in the then working-class and relatively uncivilised region of northwest France, Gauguin wrote in a letter to fellow artist Emile Schuffenecker: “I love Brittany. I find here the savage and the primitive.”

They were the notions that would, from 1891, draw him deep into the South Pacific, where his palette would explode in a riot of colour.

It was the tumultuous period in the latter months of 1888 for which Gauguin is perhaps most notoriously associated. A contemporary of Camille Pissarro and Edgar Degas, in 1888 he moved to Arles in the south of France to lodge with his friend and painter Vincent van Gogh at the now-famous Yellow House. Over the course of a turbulent nine-week period, the pair painted alongside each other before the relationship soured disastrously, leading to van Gogh’s mental breakdown and the self-severing – after a night out on the town – of the Starry Night painter’s ear, which was subsequently gifted to a local madame. Despite this, the two remained friends until van Gogh’s death in 1890.

Dr Mitzevich said the Blue Roof painting represented a breakthrough moment for the artist, whose Breton period helped change the trajectory of postimpressionism. “It is a jump-off point for Gauguin, a moment of breakthrough,” he said. “It speaks to the use of colour and form that would come later. It captures a key point in art history – the moment when the artist emerged as an intensely original master, taking impressionist colour schemes and transcending them to be bolder and more daring.”

Dr Mitzevich said the painting would be a welcome addition to the seven prints by Gauguin already in the NGA’s collection.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout