‘He drugged me for years’: John Farnham reveals predatory industry, life after cancer in memoir, Finding the Voice

In the early years of his music career, John Farnham’s life was dominated by a manipulative, egomaniacal manager whose control over the young star was so absolute that he was secretly plying him with drugs: amphetamines to keep him working all night, followed by sleeping pills in his morning coffee to knock him out cold.

In the early years of his music career, John Farnham’s life was dominated by a manipulative, egomaniacal, sexually aggressive manager whose control over the young star was so absolute that he was secretly plying him with drugs: amphetamines to keep him working all night, followed by sleeping pills in his morning coffee to knock him out cold.

“He drugged me for years and I had no f..king idea,” writes Farnham in his memoir, The Voice Inside. “I caught him one day. I was drinking a cup of coffee and there was a pill only half-dissolved in the bottom. When I asked him what it was, Darryl (Sambell) replied, ‘That’s just something to help you stay awake’.

“I feel so ashamed of myself for not realising what Darryl was up to or speaking up more often to put him back in his place. I didn’t question any of it, I just went along as if nothing was off key. I still don’t know why I didn’t react more. I put it down to being young, under stress, tired and feeling unsure and insecure about my own instincts.”

This shocking disclosure about the predatory, exploitative nature of Sambell – who managed the first decade or so of Farnham’s career – draws a sharp breath from the reader almost 100 pages into a book chronicling the life of an undisputed music icon, which began in Dagenham, England, in 1949 and has remained in Australia since he emigrated with his family in 1959.

Farnham finally fired Sambell in 1976, and the former manager died in 2001. The dubious way in which he directed the career of his young charge has been probed before, in print and on film, but the details revealed in these pages draw the extent of his deceitful behaviour into sharp focus anew.

“At the time, in the early years, he was aggressively sexual toward me,” writes Farnham of Sambell, who was openly gay in an era when homosexuality was illegal. “He would ‘try it on’ and I would say, ‘Darryl, no. Just leave me alone’, or, ‘It’s not going to happen’. I said it often enough that I can see now that this rejection turned his attraction into jealousy, hatred and a desire for control.

“For years Darryl controlled where and when I worked, what I sang, what I wore, what I ate. He isolated me from friends and family, he tried to keep me away from Jill, he drugged me, and he made me believe that all my success, everything I had, was because of him.”

Farnham writes: “Many years have passed since then and, up until now, I’ve found it very hard to unpick what happened to me. But now that I’ve confronted on it, I look back on that time with sorrow. I’m annoyed at myself for being so gullible and trusting.

“I gave away control of my career, my direction and my life. I was a young bloke and I needed a manager.”

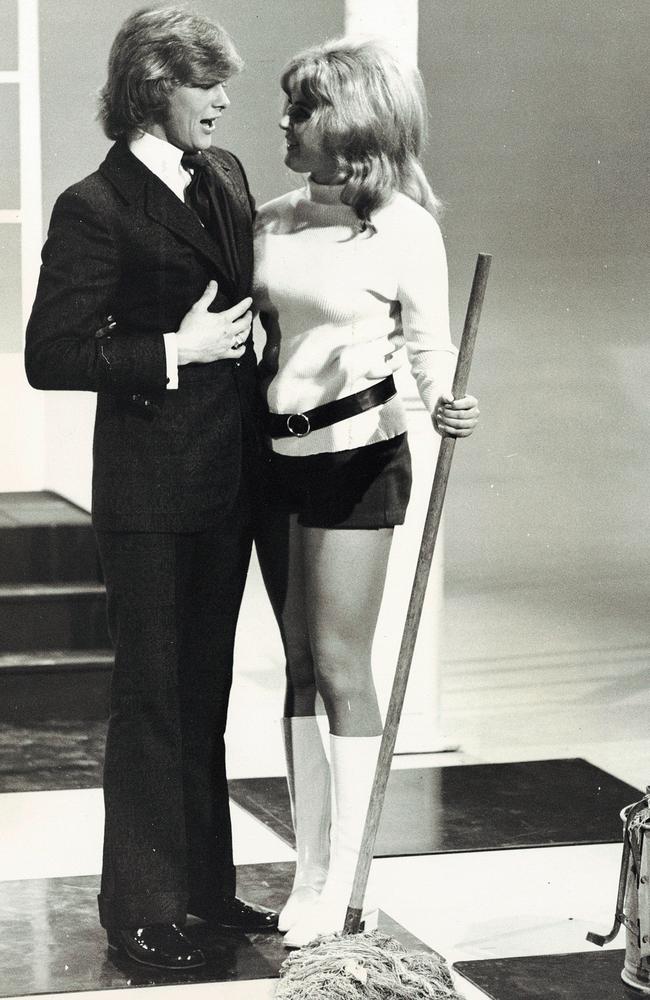

This all made for a tricky and confusing entry into show business for a teenage singer with an undeniable gift, who reflects on his younger self – whose stage name was Johnny Farnham – thus: “I was pretty, I was blond, I was blue-eyed and it turns out most people thought I was gay, or camp as it was described in those days. Darryl did nothing to dispel the myth.”

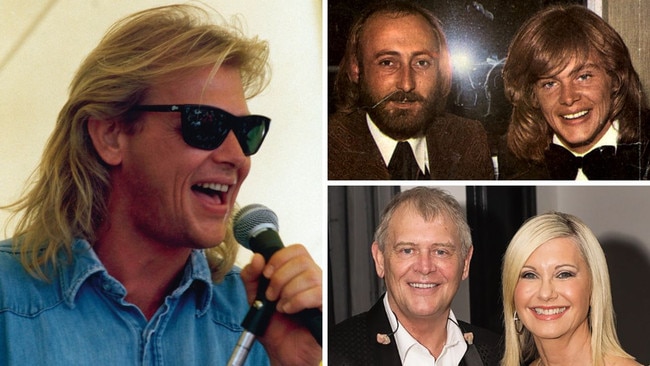

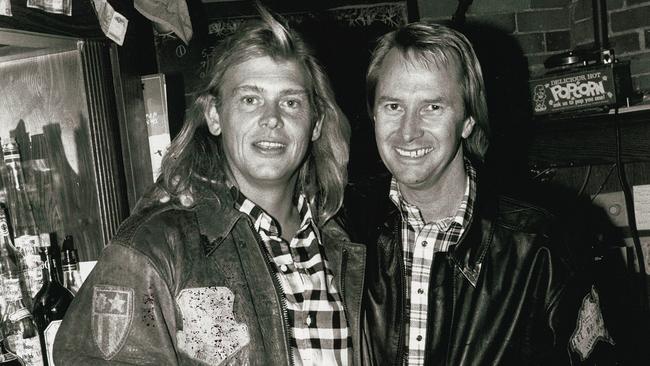

But happier times lay ahead, particularly once Farnham engaged his friend and fellow musician Glenn Wheatley as manager in 1980, while his relationship with the Jill mentioned above – his wife of 51 years, whom he married in 1973, and the mother of their two sons – has been a stabilising force amid sometimes gusty headwinds.

At multiple points in our history, Farnham could lay claim to being one of the nation’s most popular artists, if not the outright leader. His 1967 debut single, Sadie, the Cleaning Lady, became the biggest-selling single by an Australian artist of that decade, while his career-reviving 12th album, 1986’s Whispering Jack, remains the highest-selling Australian album of all time.

The man was a big deal for a couple of years from Sadie onwards, faded to near-obscurity, then roared back into the pop charts from 1987. He never really fell out of favour from then on, but what’s remarkable is that Farnham has waited until very late in the game to take up the oft-made offer of encasing his life story between the covers of a hardback.

Officially sanctioned music memoirs sometimes get a bad rap, as they’re often treated as little more than marketing tools by canny artists seeking to burnish their legacy rather than take the medium seriously. The worst of them are precisely that and, as a result, the genre has earned a perception among readers that diminishes its overall value as little more than celebrity gossip masquerading in literary garb.

Farnham’s decision to swerve the autobiography offers – while letting unauthorised works fill the market – generally speaks to good management; sometimes it’s simply better to say nothing at all. But if there ever was a time to embark on such a project, this – after enduring marathon surgery in 2022 to remove oral cancer – was surely it.

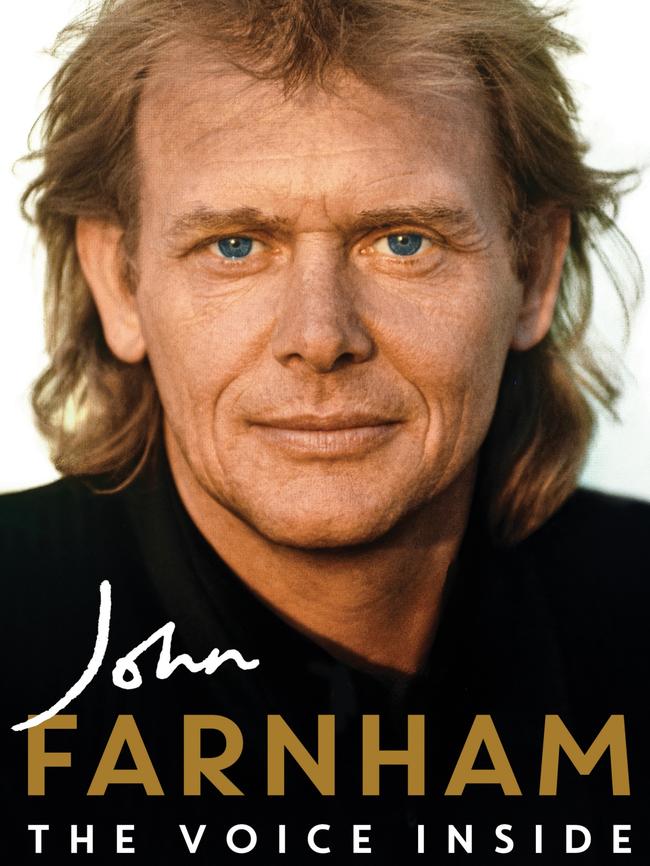

Which brings us to The Voice Inside, which Farnham has written in conjunction with first-time author Poppy Stockell, a filmmaker best known for having directed and co-written John Farnham: Finding the Voice, the award-winning and highly successful film of his life, which broke domestic box office records on release last year.

By resisting the memoir entreaties until the age of 75, Farnham has the benefit of an ability to look back at the fullness of what has been an extraordinary career, much of it housed near the very centre of the nation’s popular culture for the past 57 years.

As for where his almighty, titular voice came from, there are precious few revelations – not so unusual, perhaps, given that plenty of elite sport stars similarly lack insight into how they can perform at the highest level.

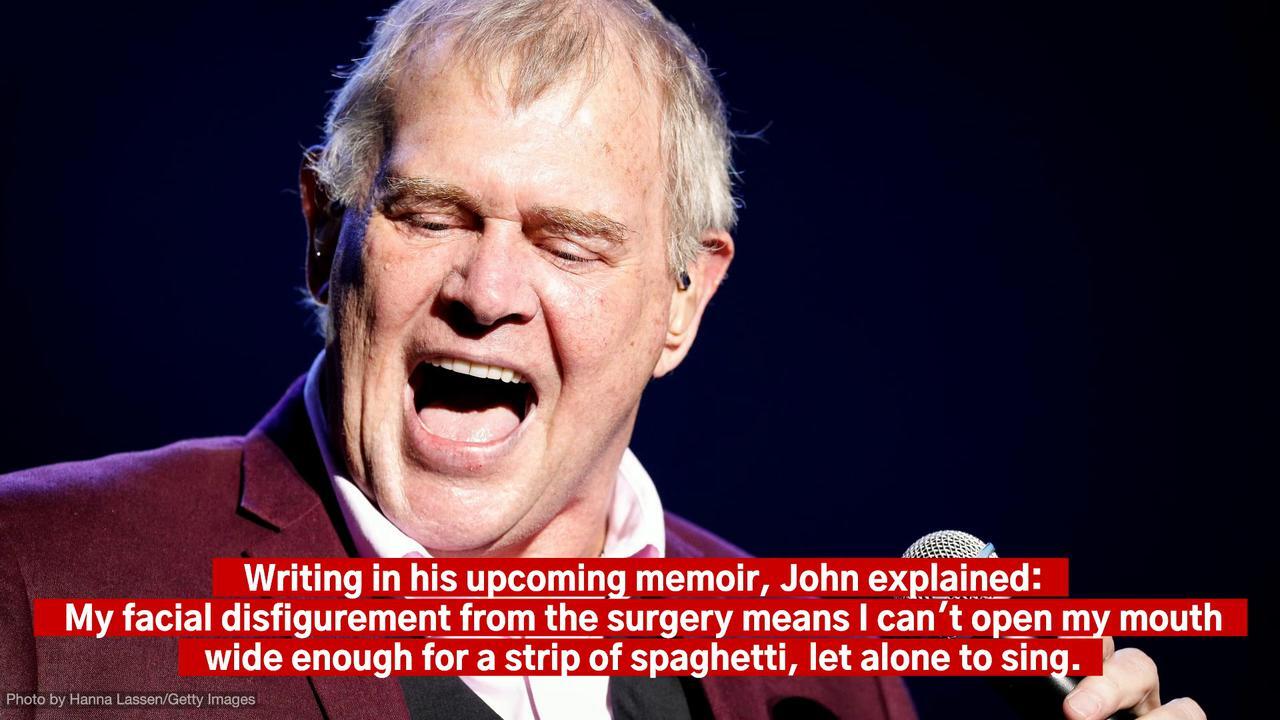

Of his signature song, for instance, Farnham writes: “I sang You’re the Voice at full voice rather than falsetto, because being a smoker my falsetto was terrible anyway. Now that I’ve quit smoking my falsetto is back, which makes me happy. It’s no good to me at the moment, but it’s back.”

Honesty, intimacy, vulnerability – these are the traits we tend to crave from this genre. And Farnham, ably assisted by Stockell as both interlocutor and co-writer, succeeds on most counts across 315 pages.

Where plenty of music memoirs begin to fall apart, though, is in the final quarter. These sections tend to become a grab-bag of dropped names and brief scenes, and the commonly felt effect for the reader is of a restless artist losing interest in the book-making process, while the interviewer tries vainly to keep them engaged enough to fulfil the project.

Farnham’s book begins to steer into this skid as it approaches 300 pages. “That reminds me …” becomes a trope, and as he runs through sketches of some of the artists he’s performed with – Ray Charles, Tom Jones, Kylie Minogue, Olivia Newton-John and Celine Dion among them – the effect isn’t too far from dictating a shopping list, and many of these brief anecdotes land with a deadening thud or shrug on the page.

For instance, on page 285, he writes: “Coldplay is one of the bands who I’ve sung with. Coldplay are good guys and their lead singer, Chris Martin, is a very nice man.” That’s the extent of the insight, and one can only wonder at the value of its inclusion.

His significant decision last year to allow You’re the Voice to be used in an advertising campaign during the Indigenous voice to parliament referendum, meanwhile, gets short shrift; that matter occupies only five sentences midway through remembering his headline appearance at the Fire Fight Australia concert in February 2020 (“I think that was the last time Olivia sang or performed on stage, and probably the last time I did too,” Farnham notes – which marks his first public statement that his live career has, in all likelihood, ended).

“When I was approached I said yes immediately, because in my mind, really, what’s it going to hurt?” he writes of the voice campaign. “How does letting a group of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander representatives offering advice on government laws and policies that directly affect them hurt non-Indigenous people? I mean, it’s not going to cost anybody anything. I only wish more people had voted yes.”

One of the unexpected strengths and surprises of the book, too, is to allow Jill Farnham a couple of chapters – in the middle, and near the end – to offer an alternative view on a public figure who has always craved privacy. “Over the years I’ve had to be strong,” Jill writes on page 295. “I’ve had to be a wife, a mother, a psychiatrist, a doctor, I’ve had to be all those things in one. I’ve had to be strong and bossy to keep the family together, to keep moving forward, and I have done that because I love John and I love my family.”

Her view, and her words, offer a vital window on the time surrounding Farnham’s eventual oral cancer diagnosis in August 2022, after the lifelong smoker had noticed a big white mass on the inside of his cheek, but delayed seeking medical opinions about it for several foolish months. These final chapters are among the book’s strongest.

On the matter of his facial disfigurement stemming from the surgery, and subsequent radiotherapy, Jill clarifies: “Because of the treatment, he lost his bottom teeth, they had to take them out. And, just for the record, they didn’t take his jaw. I know lots of people think that’s what happened, but in the end they removed the cancer from his cheek and they also scraped his jaw to make sure it hadn’t gotten into his bones … He’s still got his bottom jaw, even though the radiation has messed that up a little bit.”

Will he ever perform again? Neither husband nor wife can say.

“I don’t know if John will sing again,” Jill writes. “It just depends. Because of the radiation, that whole side of his face is rock hard. The flesh, the muscle, the tendons, none of it is supple. The surgeons need to work out how to loosen it all, so we have to be patient. He’s disappointed, naturally, because he may not be up on a stage again and he loved that.”

The man himself writes: “I still sing at home, though. I can barely open my mouth but I still wail in the shower. I love to make noises with my throat. Since I was a kid I’ve loved to whistle, I’ve loved to sing. I was given a gift and to be able to get out there and affect people in some way was a special thing. I would like to continue doing that. So, though I am not putting all my hopes into it, we’ll see.”

Much of the attention surrounding this book’s release will centre on the man pictured and named on its cover, and rightly so: John Farnham has touched millions of lives through his remarkable talents on record and on stage.

But there’s another name on the inside page who deserves special mention: Poppy Stockell, a first-time author who has made the leap from screen to print. (The film she and Paul Clarke made about the book’s subject, curiously, is not mentioned once here in the narrative, perhaps out of a strange kind of modesty; it seemed worthy of a few lines, at least.)

As the artist himself admits multiple times in these pages, he’s never been fond of interviews, having been burned early in his career as a very green, very gullible singer with zero media experience – and moreover, as a naive young man whose narcissistic, predatory and dishonest manager, Sambell, was actively drip-feeding morsels from Farnham’s personal life to newspaper and magazine writers early on.

Experiencing that sort of despicable, destabilising nonsense from someone you trusted would turn almost anyone against the prospect of being interviewed.

But this book would not exist without Farnham submitting himself to many interviews with Stockell across months of careful, thoughtful conversation; “a dance of trust and understanding” shared between them, as it’s described in a brief postscript.

It’s to Stockell’s enormous credit that she has produced such a compelling and complete memoir directly from Whispering Jack’s mouth, even as the man himself admits that today he can barely open it wide enough to suck in a piece of spaghetti.

The Voice Inside by John Farnham and Poppy Stockell is released on Wednesday, October 30, by Hachette Australia.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout