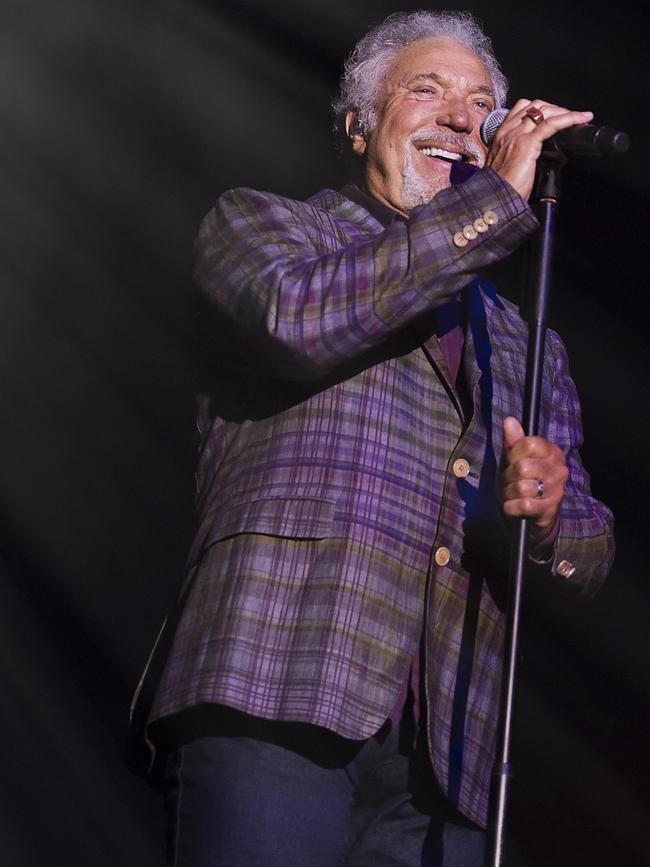

Singer Tom Jones on censorship, love and his God-given voice

Ahead of a 2024 tour, chart-topping Welsh singer Tom Jones speaks exclusively with Review about censorship, longevity and his ‘God-given voice’.

Voices come and go in popular music. Some burn out well before their time: the likes of Kurt Cobain, Amy Winehouse, Karen Carpenter and Jim Morrison each captivated us while they drew breath, and continue to do so long after they fell silent too young.

It’s a rare few who have the staying power to not only capture their talents in the recording studio as youthful performers, but continue to tread the boards reprising those notes well into their senior years.

Think Paul McCartney (81) and Gladys Knight (79). Think Mick Jagger (80) and Mavis Staples (84).

Think Tom Jones, 83, the singer who can conceive of no other thing he’d rather be doing than carrying his remarkable baritone instrument from stage to stage, across the ages, and sharing it with people around the world.

“To me, it’s a God-given talent,” Jones tells Review on a video call from his home in London. “That’s what it is. I think if you’re given something, then you should use it. But there’s a combination of things, you see? Some people are gifted with something, but they don’t have the desire to use it. Thank God I was given not only the vocal ability, but the desire as well.

“It came very naturally to me, from when I was a child,” he says. “I didn’t have to do anything to get myself up to go on stage. I think that I was born to sing. It’s the most natural thing that I do. And I love travelling anyway; I love to go to different countries. So to me, it’s perfection, what I do.”

Yet the older a performer grows, the louder become the murmurs in the crowds sitting out there in the darkened halls, arenas and festival grounds.

Two questions inevitably follow an ageing artist; perhaps they’ve already crossed your mind while reading this article. Namely: how do they keep doing it? And moreover, why do they keep doing it?

We wonder these questions because that’s all we can do, those of us who were born to love music, but never to play a note on a stage great or small.

Like McCartney, Knight, Jagger and Staples et al, Jones knows these questions follow him like a lost puppy, whether he likes it or not. Rather than take umbrage at such queries from the cheap seats, though, the singer prefers to offer an insight into what drives him today.

“If you love music as much as I do – and I’m sure Paul McCartney does as well – you don’t want it to stop,” he says. “You have such a great time making music: recording, television, but most of all, live shows. That’s why I think it’s hard for a real entertainer to not do it; to not go on stage.”

“People say, ‘Well, when are you going to retire?’ I would hate to retire,” he says, leaning forward in his chair for emphasis. “I’m going to retire when I can’t do it any longer. When the voice is not working as well as it does, hopefully the writing will be on the wall. I think the people will let me know that anyway.”

He recalls chatting with Bob Hope backstage at a venue somewhere in the US, when the veteran American comedian continued to perform into his 90s. In that moment, Jones himself adopted that familiar posture of wonderment, perhaps tinged with puzzlement, at Hope’s choice.

“I said, ‘Wow, Bob, you’re still out doing it’,” Jones tells Review. “He said, ‘Well, how do you give that up, when you go on stage and have such a great time?’”

“He was a comedian, but I imagine it’s still the same adrenaline rush when you’re up there,” he says. “Nothing can compare to it, really. You can’t really compare anything to that feeling, and that’s why people that can still do it.”

****

When the Welsh artist, born Thomas Woodward, returns to Australia next year as a headline performer at Byron Bay Bluesfest, plus six dates elsewhere, it will be almost 60 years since his second single put him on the map.

Released in 1965 by Decca Records, It’s Not Unusual – a horn-led wonder of an earworm – was accompanied by a press release that stated: “He’s 22, he’s single and he’s a coal miner.”

That single sentence contained three errors of fact: in reality, the singer was 24, he had a wife and a son, and he had never been down a coal mine in his life, owing to a childhood case of tuberculosis that kept him cooped up alone in his bedroom for the best part of two years. In his 2015 memoir, titled Over the Top and Back, Jones wrote of these bald-faced lies: “I ought to have thought about it and told Decca’s publicity department to shove it. But I was too busy getting to where I thought I needed to be. If this was the game, then, as far as I was concerned, I had to play it, in all its bullshit.”

Co-written by Gordon Mills, a successful songwriter who became Jones’s manager, It’s Not Unusual became the first in a string of hit singles that established the singer as a star.

Not long before its release, however, Mills was so broke that he took his client into a Notting Hill bank branch while seeking to secure a loan.

Mills hadn’t told Jones why he had been brought along to the meeting, and when the bank manager asked what he intended to put up as collateral, he pointed at his client. “Him,” said Mills, fingering the young man sat beside him. “He’s going to be the biggest singer in the world.” Soon enough, that prophecy – or chancy gamble, perhaps – would become true, or near enough, as Jones shot from a small coalmining town named Pontypridd to London, and became a frequent flyer capable of charming women and men alike with his singular voice.

Perhaps the best early-career showcase of his formidable power and control as a singer was on 1967’s I’ll Never Fall In Love Again, in whose choruses he hit some spine-tingling extended notes.

His first Australian tour was in 1966, and he found a firm footing in the US market, with a music-centred TV show that helped to make him a household name. Within a few years, the young man from south Wales could scarcely believe he was treated as a peer by other big voices of the era such as Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley.

Of this time, he wrote in his memoir: “As for me, I’m full of it – can’t get enough of the attention and the praise and the whirling, in-and-out-of-cars glamour of it all, and the ability I suddenly seem to have to change the atmosphere in a room just by walking into it. I get the impression very early on that I’m not going to struggle with this stuff. […] I’m confident from the off (and correctly, as it turns out) that fame, in and of itself, will not cause me a minute’s lost sleep.”

Thus began the parallel lives of Tom Jones, global star, and Thomas Woodward, an ordinary bloke with a quiet home life away from the spotlight.

As a teenager, having recovered from tuberculosis, Jones was fond of pashing his high school girlfriend, Linda Trenchard, in a red telephone booth near his childhood home. When she became pregnant at 16, the pair married, and soon began living together with her mother.

Jones learned he had become a father one day after finishing his shift working at a glove factory, dropping a coin into the pay phone and hearing a woman on the maternity ward tell him: “Congratulations. Your wife has given birth to a baby boy.”

Much later – after moving to Los Angeles with Linda and their son, Mark – the singer learned that British Telecom was planning to get rid of the old red box on Laura Street as part of a network upgrade. Jones, the traditionalist, couldn’t bear the thought of it being turned into scrap metal.

“I always thought it was a great looking phone box: it was made of iron, it was strong, it was red and it made a statement,” Jones tells Review. “I wanted to save it, because that was our telephone; the only telephone that we had in the area was right there. It was an iconic thing to me.”

After a few phone calls and some wrangling from his family members back home, the singer saved the iron box from certain destruction. It turned up one afternoon in LA, roped to the back of a lorry, and Jones had it installed beside his swimming pool with a working phone line plumbed in.

In an odd bit of synchronicity, he was by the pool in 1984 when the phone rang. He picked up the receiver and heard the excitement in his son’s voice at the other end: the red phone booth where Jones made out with his childhood sweetheart and became a father at 16 was also where, at 44, he found out he was a grandfather.

“I’ve sold the house in California, so to bring it back I thought would be a little silly, because I’m living in London now,” he says with a chuckle. “It went with the house in the end. It’s still there, because the house has been resold – and one of the selling points, I think, is that telephone box in the back garden.”

****

When Jones returns to Australia in March, it will have been eight years since his last visit, which was also booked around a major festival appearance. There, backstage at Byron Bay Bluesfest shortly before he was due to perform for about 15,000 people, Jones spoke with The Australian’s former music writer, Iain Shedden.

“I wouldn’t like to be doing the same thing all the time, and I wouldn’t want to do just a ‘greatest hits’ tour,” Jones said in March 2016. “I like to mix things up with what I’m doing now, and that’s what we do. What’s next for me is more of the same: I want to be able to sing as long as I possibly can.”

Since that last visit, he has issued his 41st album, 2021’s Surrounded By Time – his first release since Linda died of cancer in April 2016, aged 75, after 59 years of marriage.

True to what he told Shedden eight years ago, the singer continues to blend songs old and new into a setlist that spans roughly 60 years of pop, soul, blues and rock ‘n’ roll tunes, led by the silver-haired singer and his band.

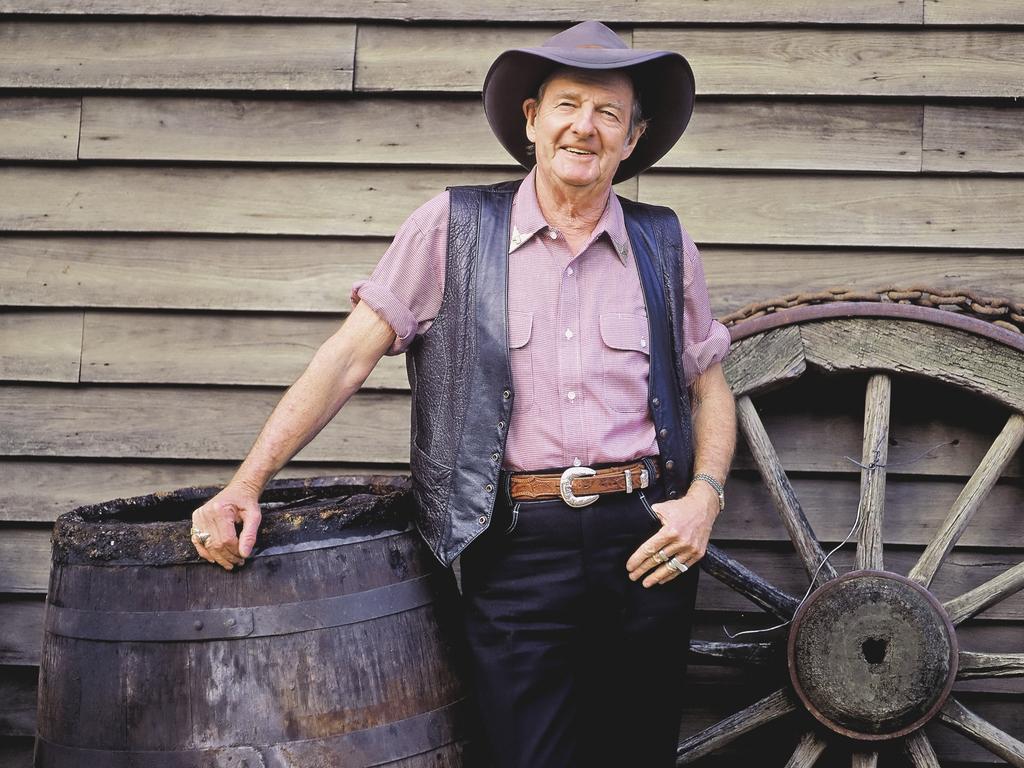

On a previous visit in 2005, Jones toured with Australia’s greatest male voice in John Farnham, where the two men shared co-headline duties.

The pair appeared together on the variety program Hey Hey It’s Saturday in 1990, where they performed My Yiddishe Momme, a song that Jones had sung on his 1967 album Live! At the Talk of the Town, which a young Farnham had admired greatly.

Watching it back today, the short segment remains a marvellous moment in Australian television history. Despite a few awkward moments in the set-up, as the two men bantered with music journalist Molly Meldrum and host Daryl Somers, their duet swiftly ascended into the sublime. They each thrilled one another with their vocal prowess, sharing smiles of supreme confidence in wielding their respective weapons.

Asked what comes to mind when he thinks of Farnham, Jones tells Review, “There’s a similarity between John and myself in the way that we got into show business: he worked in clubs when he was young in Australia, singing in clubs and pubs like I was singing in Wales.”

“But you’ve got to really love it in order to do it, and survive,” he says. “It’s got to be in you, I think, from an early age, and John felt the same way – and still does, I would hope, anyway. He’s a tenor; he sings higher than I do, as a baritone. We’re both singers in the old, traditional way of singing, not gimmicky singers. I got on really good with John, we toured together, and we had a great time.”

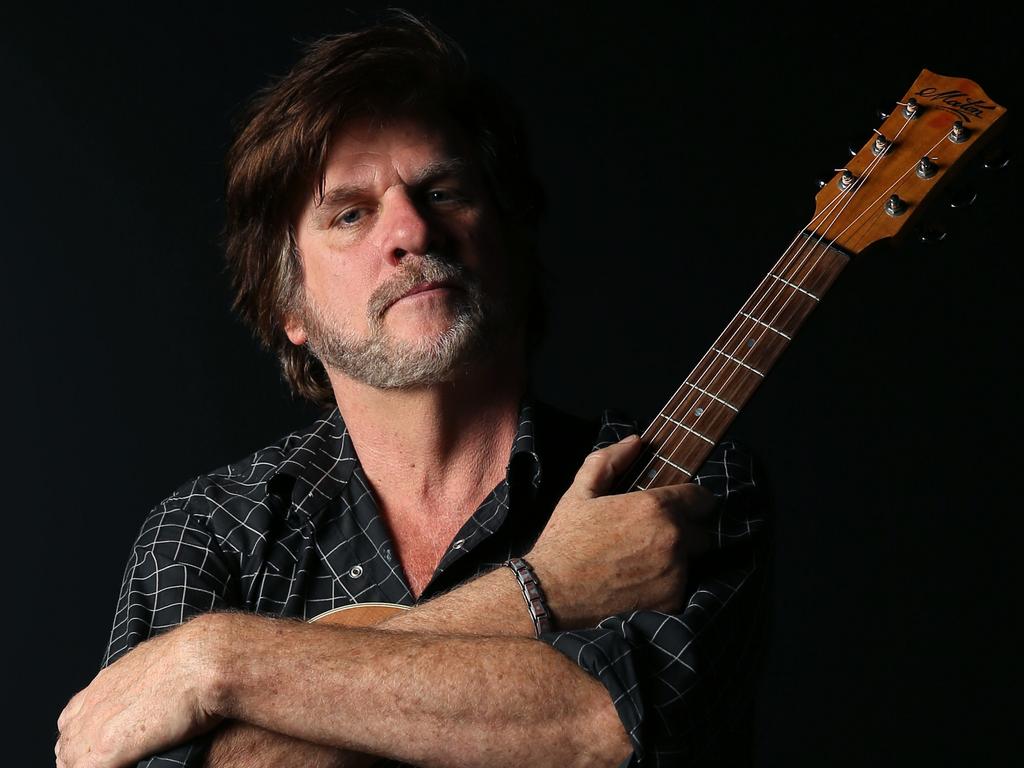

More recently, one of Jones’s biggest hits has come under fire due to changing cultural sensitivies. His 1968 single Delilah, co-written by Les Reed and Barry Mason, is a murder ballad whose protagonist kills a woman after finding her in bed with another man.

Its booming, dramatic chorus made it a chart-topper, one of Jones’s signature songs and, for decades, an unofficial anthem sung en masse by crowds at Welsh rugby games.

Like Johnny Cash’s famous lyric in Folsom Prison Blues (“I shot a man in Reno / Just to watch him die”), Delilah clearly tells a fictional story set to music.

Yet the song had been quietly scrubbed from official match day playlists since 2015, and earlier this year – on the eve of the 2023 Six Nations championship – the Welsh Rugby Union (WRU) went a step further and removed it from the choirs’ song list at Principality Stadium in Cardiff.

In a statement issued in February, the organisation said, “The WRU condemns domestic violence of any kind. We have previously sought advice from subject matter experts on the issue of censoring the song and we are respectfully aware that it is problematic and upsetting to some supporters because of its subject matter.”

Asked about this incident of censoring a song that had been known, loved and sung for decades by his countrymen and women, Jones replies, “It all depends what you want to read into. There is a crime there; it’s a crime of passion, in the song. But the guy that didn’t want the Welsh choir at the beginning of rugby matches to sing it anymore, he felt that he was glorifying a murder. Well, that’s not exactly true to start with.

“I don’t think that they’re actually thinking about somebody getting killed in the song; there’s more joy in it, than it being a crime of passion,” he says. “It’s a singer’s song, it’s a crowd-pleaser, and people like to sing it; they always join in the chorus when I’m on stage. I can’t see anything wrong with that.”

Which is why, of course, the man will continue to sing Delilah and all those other songs, loudly and proudly, for as long as he is able.

If you find yourself in possession of a natural vocal ability matched with the passionate desire to share it, keeping your mouth shut in front of a microphone would be nothing less than a crime.

Tom Jones’s seven-date 2024 tour will begin in Perth (March 21) and end in Sydney (April 4), including a headline festival appearance at Byron Bay Bluesfest (March 30).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout