Christopher Allen reviews AGSA’s The Sleep of Reason

Goya’s nightmarish scenes of violence and cruelty are a starting point for considering the demons of the psychological condition

One of the distinctive properties of the human mind, as we discussed some months ago, is the ability to anticipate the future. This is what allows us, unlike animals, to make plans, to prepare for future contingencies and to avoid dangers. Unfortunately, we still find it hard to imagine future events that are not either imminent or clearly catastrophic.

At the same time, this ability to envisage the future, and to imagine different futures, is also the source of our greatest unhappiness: hard as we find it to think clearly about long-term future scenarios, we also find it nearly impossible to be simply present. The price that the human mind pays for its expanded range of awareness is to be endlessly distracted by hopes and fears.

Some of these are vital and urgent, but many are either trivial or imaginary, and these illusory concerns seem to arise in inverse proportion to the substantial ones; in other words we tend to be most neurotic when our basic needs have been provided for. This is one of the compensations of acute crises: with something serious and objective to worry about, we may find ourselves liberated from the psychic noise of the self.

But although crises that we can understand, like wars, can help us to be less neurotic, more amorphous ones like economic recessions, domestic or geopolitical instability or the present epidemic can create a diffuse ambience of anxiety and exacerbate a sense of insecurity. At a time like this it is more important than ever to ponder the teachings of thinkers who have tried to show us how to maintain peace of mind.

At least today most people are free of the fear of hell that once plagued millions of people in different cultures, and that made death more terrifying than it would otherwise be; although even this appalling prospect could not prevent sinners from offending repeatedly. Dreadful as the menace was, its presumed distance in time made it possible to ignore for the time being.

That is why reliefs of the Last Judgement and sculptures of damned souls so often figured in the portals of cathedrals, to remind the faithful of the inevitable end of life as they entered the church. But at least the Church offered a clear pathway to salvation, as well as procedures (confession, penance) by which the sinner could be forgiven for his sins. All of this became more uncertain after the Reformation, almost exactly 500 years ago. For suddenly the universal Catholic Church – the very word catholic means universal – had been split into two broad and mutually antagonistic camps. Each side imagined it had a monopoly on the path to salvation and that those in the other camp were damned.

But what really happens in this sort of situation? You fervently believe that you are right, but you can never eliminate all doubt, and the stakes are infinitely high, because the ones who are in the wrong will be doomed to an eternity of torment. This is a recipe for profound anxiety, and one of the ways that an anxious zealot reassures himself is by hating his opponents all the more viciously.

The religious wars of the late 16th and early 17th centuries were the most brutal that modern Europe had witnessed. This is the world to which many of the prints and other works in this exhibition belong, and it is significant that they come from the northern countries of Europe, where the contest of Catholic and Protestant was most urgent and where it would culminate in the long and cruel Thirty Years’ War (1618-48). Anxiety about the split in Christendom had much less obvious impact in Italy where the Protestant movement made no significant inroads, although even there it was one of several factors that contributed to the doubt and anxiety of Mannerist culture.

In some of the works in The Sleep of Reason we can see the mood of the time evoked through classical subjects, and nowhere more conspicuously than in the extraordinary image of The Dragon devouring the companions of Cadmus, by the virtuoso engraver Hendrick Goltzius after Cornelis Cornelisz van Haarlem (1588). Cadmus, a Phoenician prince, had been sent off to look for his sister Europa, carried away to Crete by Zeus in the form of a bull, and when he failed to find her he founded the city of Thebes. There he slew a dragon guarding a spring, and sowed its teeth, mythically the first ploughing of the earth and the end of the golden age; armed men grew from the earth, whom he set to fighting each other, and he married his daughters to the survivors, creating the race of the Thebans. The engraving concentrates on the killing of two of Cadmus’s men by the serpent, evoked in an artful mixture of learned allusion and horror. Particularly memorable is the intertwining of the two figures to give the impression of one torso torn apart.

But such an image was addressed to a cultivated audience. Other more popular prints dealt with subjects known to all like Bruegel’s series of the seven deadly sins, of which two are included here, Gluttony and Pride. Following in the vein of Hieronymus Bosch, these images are densely packed with enigmatic and yet horrifying figures evoking the deformity of vice.

The exhibition contains many other remarkable works, including a number of Goya’s nightmarish scenes of violence and cruelty and the enigmatic work that gives the show its title.

One subject of particular interest that deserves our attention is that of the temptation of Saint Anthony, which was represented countless times in medieval and renaissance art, and which continued to inspire writers and artists as late as Salvador Dali. The saint was born in Egypt in the 3rd century AD and was one of the first Christians to choose a life of radical retreat in the wilderness, or the desert as it was usually called, although the term only means a deserted place, not sand dunes.

The story of Saint Anthony became famous because his biography was written by Saint Athanasius, the Patriarch of Alexandria, who is incidentally the author of the Athanasian Creed. This hagiography – to use the technical term for the biography of a saint – became enormously popular; but what really fascinated readers and artists for almost two millennia was the story of his struggle against the many temptations and trials sent by Satan. The story must have appealed to all those afflicted with the seven deadly sins. Once again this story acquired a new urgency in the age of the Reformation, when temptation could include the subtler appeals of specious or heretical thought. In the AGSA’s little painting by a follower of Bosch, the saint sits in his cell while the foreground is filled with grotesque images of the various vices.

The subject is updated in Jacques Callot’s etching made in the middle of the Thirty Years’ War (1635): here we see the saint, to the right of the centre of the composition, beset by a combination of soldiers and monsters, while a huge demonic dragon-figure sweeping down from the sky dominates the composition. Callot’s novel interpretation of the subject makes us see how the war has unleashed the destructive power of every vice, and his Saint Anthony becomes not merely a holy hermit but an everyman figure struggling against objective insanity.

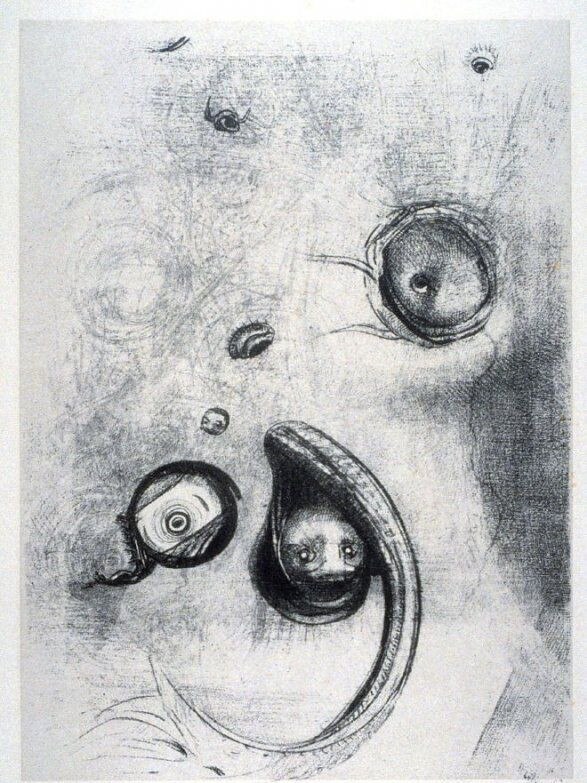

The story of Saint Anthony was given a new life for the modern period by Gustave Flaubert. Although best known today for his great realist novels such as Madame Bovary (1856), Flaubert was also drawn to the exotic oriental and ancient worlds explored in Salammbo (1862) and La Tentation de Saint Antoine (1874), a kind of prose poem written in dramatic form. There is little doubt that Flaubert’s realist novels epitomise the exquisite precision of observation and style for which he is famous; the very excess of the Tentation, for all the work that he put into it, seems to embody all the disorder, subjectivity and indulgence that he had to reject to achieve greatness as a writer. But this same outpouring of excess fascinated Odilon Redon, who devoted three series of lithographs to the subject from 1888 to 1896, some of which are in this exhibition. Redon’s prints are not literal illustrations of the saint’s struggles, but rather a series of phantasmagoric and nightmarish images that evoke the visions that assault him. There are figures of women, of Satan, of monstrous eyes. The artist is fascinated with themes of obsession, fear and madness which had already been evoked by the Romantics a century or so earlier, but which are now being rediscovered in the age of psychoanalysis.

Five centuries ago these were imagined as visitations of demons, incitements to sin and temptations that could lead to an eternity of suffering; in the romantic period they were imagined as forms of madness and melancholy, affecting either the criminally insane or the inspired poet. By the end of the 19th century, Redon’s works suggest that mental life is overshadowed by dark, unknowable and frightening impulses. The third-century hermit has become an emblem of the modern condition.

The Sleep of Reason, Art Gallery of South Australia, until August 16.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout