Christopher Allen reviews Shadow Catchers at Art Gallery of NSW

All good photography relies on light and dark but what’s in between can reveal otherwise hidden truths

The word photography literally means painting — or writing — with light but, as every artist knows, the illusion of light is only produced by the management and gradation of darkness.

This is as true in the simplest drawing as in the most elaborate painting: it is building up shadow that evokes luminosity, and it is the intensity of the darks that governs the brightness of the lights.

But shadow plays a particular role in photography, even at the most literal level. When the camera lens is opened, the photographic film is burned, so to speak, by the light to which it is exposed, so that the most brightly illuminated areas of the subject become shadows on the negative. When, subsequently, light is projected through the negative in the enlargement process, that light in turn burns the photographic paper; but less or no light comes through the dark parts of the negative: they remain unmarked by the enlarger’s lamp and thus, by a series of inversions, come out once again as highlights on the finished print.

The earliest pioneers of photography, as is noted in the catalogue of this exhibition, were fascinated by the theme of shadow.

Louis Daguerre wrote of arresting the fleeting shadow on the paper, and Henry Fox Talbot considered skiagraphy — drawing with shadows — as an alternative name for photography. All black and white pictures are based on light and dark, but when we consider the earliest photographs, such as Camille Silvy’s portrait of Mrs Godman (1862), we have an especially strong sense of the subject as emerging from, and almost constituted by, the surrounding shadow, all the deeper in her case because she appears to be in mourning dress.

We usually think of photography as upsetting the traditional making of images by introducing a new and vividly naturalistic mechanical process. That is true, but it must also have brought with it a new kind of melancholy that has accompanied photographic images ever since: that they are the direct imprint of the world, but of a single ephemeral moment, doomed to vanish as soon as recorded. Paintings take time to make, and they condense time into something more durable; photographs commemorate the elusiveness of experience.

Photographs also flatten the complexity of three-dimensional visual experience, with its endless potential points of view, into a finite, two-dimensional image. The choices of framing and timing that produce such an image are fundamental in this process. As we have often mentioned, however, it is treacherous for painters to rely excessively on photographs as a shortcut in their own work, although they may suggest ways in which complex phenomena can be converted into pictures.

This is something that photography has in common with mirrors, which are ubiquitous in the present exhibition. Leonardo da Vinci suggested using mirrors to check one’s painting, as anything askew will be much more apparent when seen in reverse, but also to look at the world. For the mirror, like the photograph, flattens the world into a picture and allows the artist to see elements of a landscape, for example, as parts of a pattern: the painter has to unlearn many of the habits of common perception, and one of these is the separation of all the things in our field of vision into different spatial planes. Composition requires that all elements in the visual field be projected onto a single plane.

Not surprisingly, then, photographers have instinctively loved mirrors almost from the very beginning. The portrait of Mrs Godman mentioned above also includes a mirror, so that while the sitter faces us, the upright mirror behind her captures her turned three-quarters away from us in profit fuyant or profit perdu; the young widow in mourning faces us, but is also captured looking away into the depths of memory and sorrow. The picture itself, meanwhile, is a black and white pattern of light and shadow, whose fleeting quality is emphasised by the image within the image.

“Humankind lingers unregenerately in Plato’s cave,” as Susan Sontag writes in the essay of the same name in On Photography (1977), “still revelling, its age-old habit, in mere images of the truth.” One of the most remarkable things about this essay is the way it anticipates habits that have become exacerbated in the age of the digital camera and the smartphone: “Most tourists feel compelled to put the camera between themselves and whatever is remarkable that they encounter. Unsure of other responses, they take a picture.” She goes on to develop her argument about the essentially passive, non-interventionist, voyeuristic nature of picture-taking.

But it would be interesting to know who first saw the analogy of photography with the famous allegory in The Republic (c. 375BC), in which Plato imagines that the world we know is a shadow-play reflected onto a cave wall and that we cannot see the real bodies that are casting these shadows. In the same way, photography can capture patterns of light and dark with great accuracy but they remain mere shadows of an unknown reality. Some similar, post-photographic, intuition seems to lie behind the intriguing shadow drawings of Georges Seurat, in which the figure seems often no more than an interruption or a lacuna in the flow of light.

And yet although pictures of mirrors remind us of this endless play of illusion and uncertainty, it is also a trope of such compositions that the mirror reveals something that cannot otherwise be seen from the camera’s point of view. One of the most memorable of such images is Ilse Bing’s famous Self-portrait with Leica (1931). On the left, the mirror presents an objective view of what is taking place, with the profile of the photographer as she looks intently through the camera, mounted on a tripod; on the right, however, the artist faces us directly, one eye looking at us and the other replaced by the camera lens.

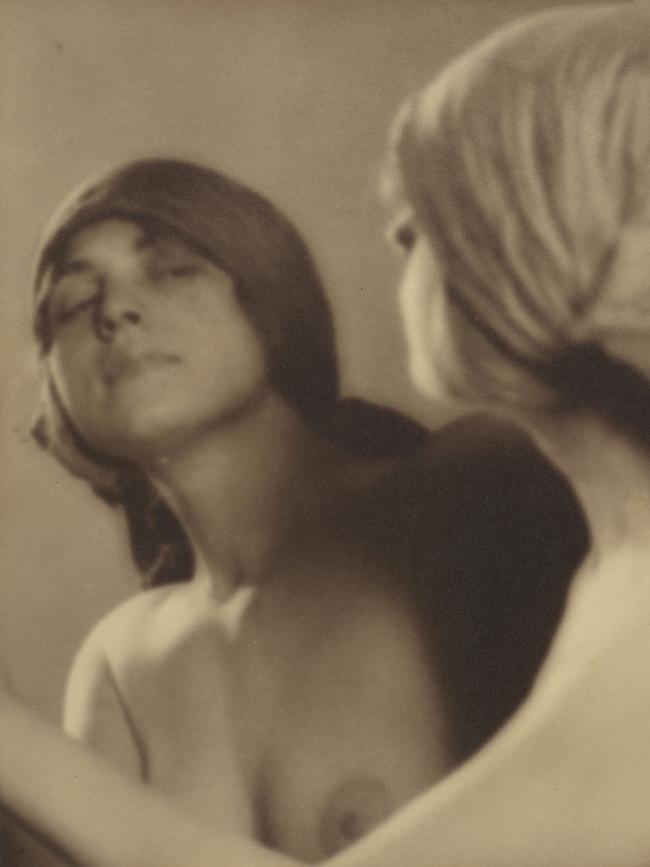

In another picture, FM Tuckerman’s At the Mirror (1928), a young woman seen in profit perdu holds a large mirror in which everything that we cannot see in the primary figure is revealed: her face, her hair, her breast. The composition is framed by the arm holding the mirror, yet its edge is not visible, so we are able to sink into the boundless world of the reflected image.

In contrast, in AW Gale’s Girl Brushing her Hair (1932), the subject is holding a tiny pocket mirror into which she looks intently. At the distance she is holding the mirror, she can only see a part of her own reflection, and has to tip her head forward to see the top of her hair. We, on the other hand, cannot see the reflected image at all; here the mirror does not reveal anything to us, but on the contrary emphasises the subject’s own absorption in herself and her own action.

It is curious that some of the most interesting pictures in the exhibition are from the first half of the 20th century. They are often small or even very small, and they date from before the age of the mass consumer industry, which especially took off in the third quarter of the 20th century. This was perhaps the golden age of photography, when there was still something enchanted about the photographic image — especially under the influence of surrealism — and before it had become associated primarily with political and commercial manipulation and consumer bulimia.

We need only think of mirrors in the work of Magritte, among many other painters, or the prominence of the motif in Jean Cocteau’s films La Belle et la Bete (The Beauty and the Beast) (1946), where a magical mirror allows Belle to travel from the Beast’s mysterious castle back to her father’s house, or especially Orphee (Orpheus) (1950), where the eponymous hero enters the underworld through a mirror. One of the enigmatic pronouncements that Orphee listens to so avidly on the oracular radio broadcasts from the world of the dead is a play on words that for once translates into English: les miroirs feraient bien de reflechir — mirrors would do well to reflect. It is a line that also comes to mind before Max Dupain’s photograph of an elaborate but blank mirror on a wardrobe (c. 1951-52).

Shadows too could reveal an unseen truth, or something not apparent in the primary image, most literally in Hans Hasenplug’s Untitled (Girl on a Wharf), 1937. Here the figure is seen from above, in an extreme foreshortening that contrasts with the long shadow cast by the rising or setting sun that occupies most of the composition. But the shadow also allows us to understand the posture of the girl, standing with her hands on her hips. Athol Shmith’s Woman in a Fur Coat (c. 1940s), on the other hand, uses the motif expressively and rather menacingly: the seated woman is dwarfed by her own shadow cast on the wall behind her.

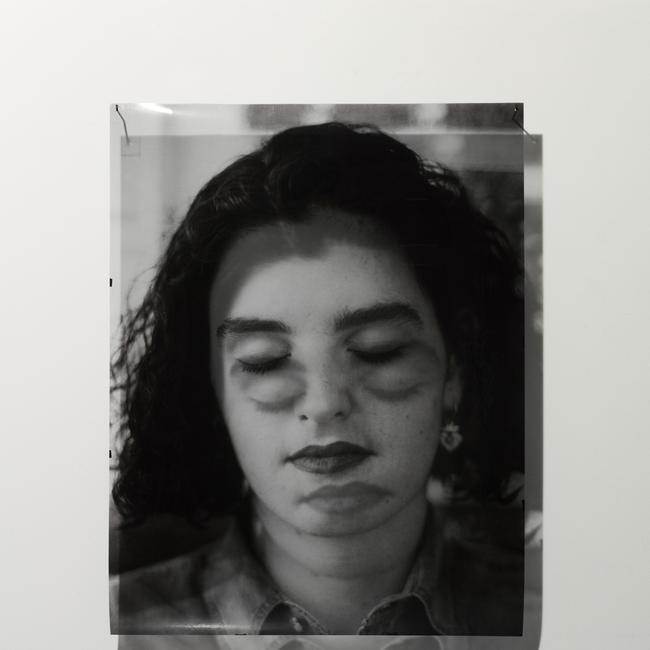

Among recent photographic works in the exhibition, one of the more striking is a series by Merilyn Fairskye made in 1995, in which portraits have been printed on a translucent film and hung at a little distance from the wall. Diagonal lighting passes through these images to project a secondary image on the wall behind, evoking a disconcerting doubling and ambiguity behind what is ostensibly a perfectly straightforward portrait shot.

Another is Ann Balla’s double exposure of a young girl putting on a pair of swimming goggles. In one of these exposures she is facing the camera, while in the other she leans forward and to one side as she reaches up to adjust the strap of the goggles. Each of these images is printed as a shadow version of itself, ghostlike and diaphanous. Only where the two images overlap does the tone of the image become darker and legible as a normal photograph: but then both images become simultaneously legible and compete for our attention, reminding us of the fleeting instants captured by the camera.

One of the most intriguing pictures in this exhibition, Lucien Herve’s Paris 1948, is so small — less than 6cm x 5cm — that one has to look carefully just to read the image. The composition is occupied by a wall on the left and a staircase on the right, going up to the top of the wall and to a barely glimpsed area above. In the corner formed by these two elements, a shadowy figure can just be made out standing in an arch of light. But what appears to be an archway may in reality be sunlight coming through an unseen archway on our right and shining on the dark wall. And the shadow figure, wherever he really is, is not so much a presence as, like Seurat’s drawings, a flickering, momentary absence in the stream of energy and being.

Shadow Catchers, Art Gallery of NSW, until 2021.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout